Theatre in Palm -projektin päätösfestivaali Roots & Routes – A mosaic of rising artists pidettiin Kyproksella 11.–13.4. 2025 (Cypros Theatre…

Overview of Educational Needs and Next Steps for Kenya`s Fish Farming Sector: An Educational Approach

Abstract

Over the past decade, Kenya’s fish farming has experienced tremendous growth in production, contributing to improved incomes for the industry and animal protein for consumers. Despite improved management practices and technologies at the cage, hatchery and production levels, and improved availability of high-quality feeds locally, there are still major gaps between the availability of HE and VET education in fish farming and with increasing demand. This growth has mainly been driven by the large-scale cage farming around Lake Victoria. We are proposing new content for the existing curriculum linked with aquaculture. Hereby, we focus on the development of business and economy education of aquaculture, i.e. supply chain management and or industrial economy and engineering.

In addition, we highlight the status of aquaculture as an attractive career alternative for students. The purpose is not to totally rewrite new curricula, but instead add some vital aspects in aquaculture from the economic perspective.

1. Introduction

This paper presents an overview of the needs of business and economy education content in partner universities. The purpose is to develop and create some new content for the aquaculture education and curriculums of Rongo University and Great Lakes University. This is based on observations made by Otieno and Rewe (2024) in their articles collecting information about the future needs and bottlenecks of present aquaculture education as well as highlighting the present curriculums linked to business, entrepreneurship and economy. The universities are at different levels and the educational contents are variable and not comparable.

This paper presents existing educational gaps and capacity, and shows a way forward for priority educational needs in terms of socio-economics, land use changes, skills and knowledge.

The purpose of this paper is to document: information that is currently available from previous research; the existing scientific capacity; and the resources required to guarantee that Lake Victoria remains an attractive target for the next generation of fish producers. It is clear from this synthesis that the biological, social, and economic benefits that can be derived from Lake Victoria can only be accomplished through the utilization of a multi-disciplinary educational approach as well as the modelling of all potential interactions in the aquaculture business.

The background to this paper lies in the feedback which has emerged in the field. The lack of skills in economy and related fields is notable. This paper tries to focus on future studies of economics for future fish farmers. The paper will also highlight new structures for improvement in aquaculture education with special reference to business and economy.

2. Food Security and Lake Victoria

Over 42 million people rely on Lake Victoria as their primary source of food, employment, and clean drinking water. The lake’s fisheries have produced around one million tons in recent years, but the lake’s growing population has resulted in a lower catch rate per capita. Additionally, the lake and its catchment have been negatively impacted by a wide variety of human activities, such as overfishing, oil spills, discharge of untreated waste, spread of invasive species, over-abstraction of water from the lake basin, and climate change, among other drivers of change.

Picture 1. Lake Victoria watershed.

3. Aquaculture at Victoria Lake

In recent years, demand for fish and fish products has increased despite a plateau or reduction in landings of the main commercial species in Lake Victoria (Nyamweya et al., 2022). This, together with increased demand for the African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) fingerlings for live bait fishing in the Nile perch fishery have stimulated aquaculture investments in the lake region, resulting in increased demand for aquaculture inputs such as seed, feed, and equipment. In response, many private catfish hatcheries have been established to meet the tremendous demand for catfish bait (approximately 3 million pcs/day) and food fish in the Lake Victoria region (Isyagi, 2007).

The Lake Victoria basin is generally suitable for aquaculture development on both land and water (Ssegane et al., 2012). The majority of rural fish farmers use ponds to raise fish on a subsistence scale for household food security (Maithya et al., 2007; Mwanja et al., 2007). Commercial aquaculture producers use both land-based (ponds/tanks) and water-based (cages) production systems to raise Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), African catfish, and ornamental fish (Jacobi, 2013; Munguti et al.,2006; Rutaisire et al., 2010).

Picture 2. Fish ponds at the Victoria Lake watershed.

Subsistence aquaculture production from land-based systems is still low, but this can be improved through the integration of aquaculture-agriculture systems and provision of supplemental low-cost feed (Mwanja and Nyandat, 2013). On the other hand, substantial yields (40–120 kg/m3) are currently being realized using tilapia cage farming, with the potential to meet the region’s need for fish (Musinguzi et al., 2019).

The number of fish cages has risen considerably in a short period of time. In 2012, the Kenyan portion of Lake Victoria had very few floating aquaculture fish cages. This figure has risen dramatically, with Njiru et al. (2019) stating that over 3,000 cages had been installed on the Kenyan portion of L. Victoria. Hamilton et al. (2019), on the other hand, counted 4,357 fish cages covering 62,132 m2 on the same portion of the lake in 2018 utilizing unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), satellite, and GIS technology. By April 2022, the number of cages in the same section of the lake had risen to 5,252 (KMFRI unpublished data).

There are emerging concerns about the impact of aquaculture investments in Lake Victoria if best practices are not followed. These include loss of biodiversity, the introduction of fish pathogens, and the safety of products (Egesa et al., 2018; Musinguzi et al., 2019; Namulawa et al., 2020; Opiyo et al., 2018; Tibihika et al., 2020; Walakira et al., 2018). Biosecurity and biosafety policies for aquaculture should be implemented to ensure sustainable growth of the sub-sector.

Picture 3. Typical cages at Victoria Lake. Fishfarms are small in size.

Farmers have organized themselves into associations/groups to access services, markets and inputs, which has accelerated aquaculture development in this region. Other efficient innovations include the use of recirculating aquaculture systems that are suitable for seed production on a small area (Gukelberger et al., 2020; Opiyo et al., 2018). Aquaculture can be used to conserve threatened aquatic species, through the promotion of ‘‘finger ponds’ established in wetlands, and these have the potential to restore biodiversity (Kipkemboi et al., 2007). Species (Tilapia: Oreochromis niloticus, O. variabilis, O. leucostictus), Clarias sp., Protopterus aethiopicus and Haplochromis spp. are reported to have migrated to finger ponds and are breeding to increase fish production. Currently, efforts are being made to monitor the impact of cage farming in Lake Victoria and propose mitigation strategies through integrated multi-trophic aquaculture to guide planners in the region (Hamilton et al., 2019).

4. Existing Educational Capacity

Fisheries science is taught in all three Lake Victoria riparian nations, and the number of universities that offer it has increased in recent years. Most universities provide bachelor’s level training in fisheries, aquatic, marine, and aquaculture sciences, with only a handful providing postgraduate training in the same subjects. Certificate and diploma level training is available in the region’s vocational fisheries training institutes. There are likely to be significant gaps in environmental education training and capacity building. Very few institutions provide master’s degree programmes in environmental sciences.

Almost all public universities that provide science-based programmes have environmental programmes at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels. In Kenya and Tanzania, many generic programmes in biology, aquatic ecology, and fisheries science address challenges connected to coastal zone management. There are also graduate-level programmes in geographical information systems. In addition, many universities and colleges provide short courses in GIS and remote sensing to train students and those currently working in the area on modern mapping techniques which are in demand in the labour market.

5. Gaps

Quite many university provide undergraduate and graduate programmes that include the concept of fishing technology. They offer undergraduate and postgraduate food processing degrees, but none expressly target fish processing or business topics related to fish farming entrepreneurship. In addition there are with some components on public health and hygiene, fishery policy, law and institutions, fishing methods and gear technology, and fish handling, processing, and preservation.

6. Discussion

The literature cited here reveals that there are a variety of courses linked to aquaculture at universities in the Lake Victoria watershed area. Lake Victoria’s importance to the socioeconomic and nutritional well-being of lake-edge communities and riparian countries through the provision of numerous ecosystem goods and services cannot be over emphasized. However, the lake is under tremendous strain because of human activity and climate change.

The complexity of the ecosystem, along with negative human impacts on the lake and its catchment (sometimes without prior studies of potential impacts), have hampered our understanding of the system dynamics, major processes, drivers, and responses. Efforts to collect data about the lake and its catchment often focus on one or a few components (such as water quality parameters, aquatic species, land use, pollution, climate factors etc.) of the ecosystem and are generally limited in time and space. This is because much of the basic research is donor-funded and led by expatriates, while national governments do not adequately fund long-term research programmes that allow local skills to develop, despite the existence of many higher learning institutions that offer advanced training in various fields relevant to the management of Lake Victoria and its catchment. This review identified key research needs in Lake Victoria and its basin that could result in a coordinated and efficient approach to higher and VET education to understand the past, present, and future of aquaculture and Lake Victoria.

We suggest here that the HE and VET education of aquaculture should be based on holistic, environmentally and economically sustainable curriculums. There is also an urgent need to raise and highlight the status of aquaculture as a career. It is commonly only seen as a “last career alternative” and those with a master’s degree or post graduate degree are almost totally absent from the business. To gain a better status a higher quality of education is needed. It is necessary to show that there are many business opportunities in aquaculture not only involving fish cages.

7. Some Observations of Curriculums in Industrial Economics

In the following chapter we present some course examples involving industrial economics being given at the Turku University of Applied Science. The purpose is not to copy the curriculum in its entirety, but instead to select suitable courses to be added to the existing curriculums in the GLUK and Rongo Universities. The new compilation is made together with all participating universities. In this WP we focus on courses and sub courses linked to business and the economy.

The planning of curricula was made using the MiniMOOCs /nuggets planning tools. The idea is to provide series of MiniMOOCs (or nuggets) to cover the “missing parts in the contents of business and the economy in bachelor’s and master’s level education.

7.1 What are MiniMOOCs ?

A MiniMOOC (Mini Massive Open Online Course) is a short, online course designed for a large number of participants. It is a condensed version of a traditional MOOC, typically lasting from a few hours to a few weeks. MiniMOOCs often focus on specific topics or skills and are designed to be easily accessible and self-paced. Key Features of MiniMOOCs are:

- Focused Content: Covers a single topic or skill in depth.

- Short Duration: Usually from a few hours to a couple of weeks.

- Open Access: Often free and available to anyone with an Internet connection.

- Interactive Learning: May include videos, quizzes, and discussion forums.

- Certificates: Some offer certificates of completion.

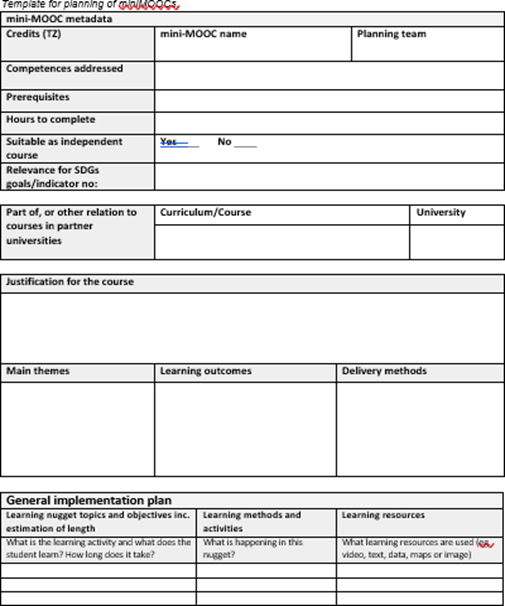

An example of a MiniMOOC planning table is shown below:

7.2 General division of economy topics

We suggest here that in the revised aquaculture education programme supply chain management should provide the basic frame for business education and MiniMOOCs (or nuggets, which are smaller entities than MiniMOOCs) should cover the following topics: the MiniMOOCs should provide 2 to 4 credit points (European standard).

8. General Structure

It was clear from the results from our enquires from stakeholders that fish farmers need to possess more skills than should be reasonably expected of anyone. It is necessary to repair equipment, process and market products, keep books, hire and fire staff, arrange financing, and carefully watch over stocks of fish or shellfish, to name just a few tasks. All of these responsibilities are overshadowed by three fundamental concerns:

- Who will buy the product?

- How will you produce the product?

- Will revenues adequately exceed costs?

- How are costs formed?

8.1 Section I

A. Pre-planning, expectations of fish farming

Every business owner wants success, but everyone has a unique definition of success resulting from individual experiences, prospects, and goals. Only you can decide what is to be achieved by your aquaculture venture. It is useful to establish expectations before developing a plan. This helps to avoid the natural, stubborn tendency to forge ahead even though major undesirable compromises will result. A clear understanding of your enterprise goals will guide decisions throughout the planning process.

B. Determine Market Area

A practical way to analyse potential markets is to define a serviceable geographic area. Whether you are delivering a product or expect to attract customers as in a fee fishing operation, the travel distance and time are major considerations. A one-person operation for example, might be hard-pressed to allocate even a couple of hours per day for deliveries. A fish farm with a partner or employee responsible for deliveries could market to a wider area. A rule of thumb derived from farm markets is that the majority of customers for on-site sales will come from a ten-mile radius of your location.

C. Identify Market Segments

Within a market area there will be different types of customers. You must learn to examine if there are enough potential buyers for your product to support your business. The principal customer types (market segments) for aquaculture products are: wholesalers, restaurants, seafood stores, supermarkets and consumers buying directly. Other customer types might include sports fishermen at fee fishing operations institutional buyers, pet stores for ornamental fish and bait dealers. You must determine which segment(s) you are going to serve.

D. Byers and Needs

We need knowledge about the fish and shellfish markets because of their dynamic seasonal variability. Industry trends are also important considerations that affect buyers’ needs and expectations. Each market segment has its own buying patterns, based on quantities purchased product forms price, and delivery. Talk to as many different buyers as possible to obtain a representative picture of their needs. Some aquaculture products have well-established markets while others face uncertain markets. A visit to a seafood wholesaler will yield more useful information on oysters than on tilapia.

E. Market potential

Market potential should be estimated by extrapolating information to the number of buyers within your area.

8.2 Section II: Production feasibility

A. Getting Started

After determining the practical and market feasibility of your operation, you should examine its production feasibility. The critical question is: “Can I efficiently and economically produce my proposed aquaculture product?” Many approaches are used to select a culture species.

A species maybe chosen because it is in short supply, a lucrative market exists or it is easily cultured. Successful production requires as much knowledge as possible about its biological and production requirements. After considering the culture species and systems, you may determine that permitting, construction, seed and feeding costs at your site will exceed the potential production income. This information will save you money, time, and frustration. This section and the accompanying worksheet will help identify problems that limit operational success.

B. Fixed and Variable Costs

We have to learn distinguish between fixed costs and variable costs of production. Fixed costs are associated with those inputs which do not change over the short run such as salaries, overheads, insurance and depreciation (capital expenses).

Variable costs are dependent on the level of production and will change as you increase or decrease your stock. They include juveniles, feed, chemicals, labour, electricity, etc. Operational expenses and potential profitability for alternative culture systems and scales of operation can be calculated by examining these two kinds of costs.

C. Inputs

Stock (seed fingerlings, etc.), feed, and labour costs are the most expensive variable costs of a culture operation. It is important to analyse these costs carefully to ensure they are accurate and manageable.

Production is limited by the number of organisms stocked. Stocking rates unit costs growth and potential mortality of culture organisms should be available in the resource materials. These values can be evaluated to determine profitability if higher than expected seed prices or mortalities are encountered.

D. Feeds

Most fish production systems require supplemental feeding. Because of the volume and price of feed, the equipment needed and the labour required, feeds and feeding are costly—up to 40-50 percent of the total variable costs. Thus, profitability is often determined by the feeding efficiency. The amount of feed required is determined by feed conversion rates and can be estimated from various formulas.

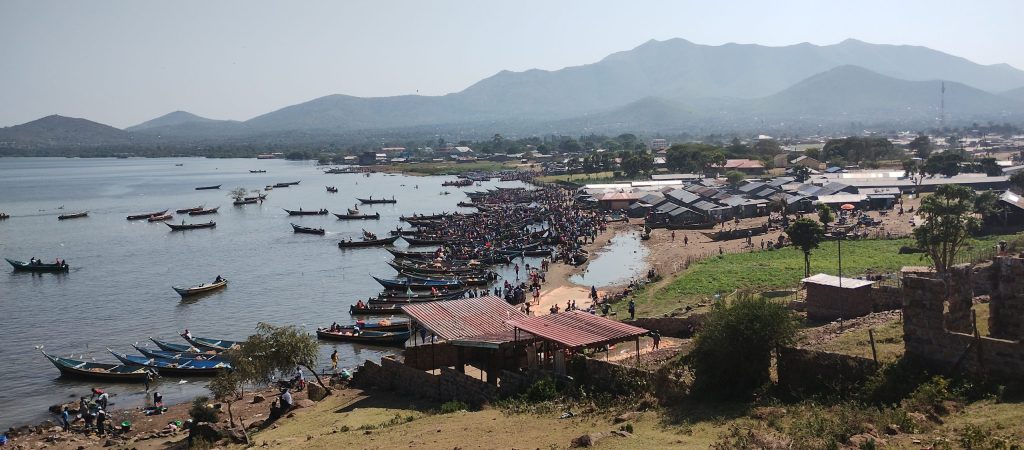

Picture 4. Traditional fishing is still important at Victoria Lake.

E. Management

Management of an aquaculture facility often requires more time and expertise than traditional farming activities. The ability to make quick management decisions and take prompt action is crucial, particularly when stocking, feeding and harvesting fish.

Estimate your needs based on experience, from discussions with other growers, or from technical studies. Determine if you have the necessary knowledge, skills, time and labour. If periods of critical decision making conflict with other activities can you hire the necessary assistance? Include realistic estimates of your availability and costs, including resources or the cost to obtain them.

8.3 Section III Financial feasibility

In this final section the overall picture of your business will emerge by constructing a cash flow statement.

A. Importance of a Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement is the most important of several financial documents included in a formal business plan. It is a tool for forecasting profits and ensuring that money is available when needed. A business can fail even if it is profitable. If profit comes in after creditors have closed your door, it will be too late.

The cash flow statement shows how much money you need, and when you need it; how much money you are bringing in and when it is available. This is essential information because aquaculture production is often discontinuous. Fish and shellfish take months to grow to market size, and during this time expenses will be incurred.

Knowing in advance that a cash gap will occur allows you to budget for it. Cash flow projections also include timing of capital investments, putting idle cash to work and lessening dependence on debt. Interest payments maybe minimized by borrowing as needed rather than annually or sporadically.

B. Some other issues

It will be important to learn about long haul logistics and/or local delivery, as well as available storage options such as cold chain facilities. If the aim is to operate at an international level, the focus will involve technical commercialization, international business, operating in international networks, in addition to multicultural teamwork and interaction skills. Furthermore, production management, enterprise resource planning (ERP) and approaches such as LEAN may be useful to learn.

9. Production and Industrial Economics

In this chapter we present one example of the connect of industrial engineering curricula being kept in Turku University of Applied Science. The example is from the BSc level (technology).

Degree title: Bachelor of Science (BSc)

Scope: 240 credits

Duration: 4 years (240 credits)

9.1 Description of the courses

Industrial economics education at Turku University of Applied Sciences is a broad-based technical-economic education programme that offers a diverse and developing study environment for students. Teaching takes place in close cooperation with the business community.

Students grow into entrepreneurial professionals capable of independent and teamwork, who are sought-after employees in the companies of the region. Applied research and development activities are closely linked to the education through business projects, theses and internships carried out by the students.

The education is international and all students complete an internationalization component in their degree, either during an exchange study period or in an international internship. The education also offers the opportunity to complete a double degree in Germany or France. A double degree means that upon graduation, the student receives both Finnish and foreign degrees.

The aim of the basic studies is to give the student a broad overview of the key areas of industrial economics and its position in society and in companies. The student learns to consider what solutions can promote sustainable development from the perspective of industrial economics. Basic studies also provide the language skills required by regulations.

The aim of vocational studies is to deepen the student’s competence in the chosen vocational competence path in industrial economics, which are predominantly production planning and sales work.

9.2 Structure and content of education and competencies path

Core competence; (basic studies) 90 ECTS

Extended competence (vocational studies) 150 ECTS:

- Industrial economics oriented modules

- Technically oriented modules

- Elective studies 30 ECTS

- Internship 30 ECTS

- Thesis 20

Basic subjects supporting vocational subjects are scheduled and tailored in terms of content and scope according to the needs of business life.

- The competence themes of the first year of study are entrepreneurship, industrial product and production, and the basics of industrial economics.

- In the second year, the students will familiarize themselves with the organizational competence perspective of industrial economics, sustainable development, technical trade, and supply chain management, and deepen their competence in the competence path they have chosen. The two competence paths are production and sales.

- In the third year, the focus is on technical commercialization, international business and operating in international networks, and multicultural teamwork and interaction This period involves either an internship or study abroad. The thesis will be started.

- The fourth year of studies deepens the knowledge of business management and leadership. The studies are carried out by applying and deepening the knowledge in challenging business development tasks that require innovation and initiative. In the final year, the industrial economics competence path studies are completed.

9.3 Career and further study opportunities

Engineers who graduate from the industrial economics education programme will have the skills to work in demanding expert and development tasks in business. The tasks may be related to areas such as technical sales, technical procurement, supply chain management, product development management in service business, production and process development and management, or international tasks. The education also provides the tools for starting, developing, and managing a business.

9.4 Examples of job titles

Job titles may include, for example, purchasing or export engineer/manager, sales manager, production or project engineer/manager, production planner, development manager, quality manager, product manager, factory manager, etc.

Next the structure of curriculum is presented divided by 3 broad entities: Core Competence (90 cr), Engineering Basic Skills (15 cr), Operation Management (15 cr), Engineering Applied Skills (15 cr).

| Code | Name | Credits (cr) |

CORE COMPETENCE ENTITY (Choose ects: 90) |

90 | |

| TE00CJ47 | Introduction to Industrial Management and Engineering Studies | 2 |

| TE00CX60 | Business and Sales | 5 |

| TE00CQ16 | Engineering Precalculus | 5 |

| TE00CX59 | Engineering Physics | 5 |

| TE00BY86 | Information Technology | 2 |

| TE00CW93 | Basics of Programming | 3 |

| TE00CT41 | Basics of Technical Fields | 2 |

| 5011098 | Physical Research | 3 |

| RUOTSI3 | Swedish Communication | 3 |

| YO00BF11 | Swedish for Working Life, Oral Communication (replacing compulsory Swedish) | 1 |

| YO00BF12 | Swedish for Working Life, Written Communication (replacing compulsory Swedish) | 2 |

Engineering Basic Skills Module (Choose all) |

15 | |

| 5091107 | Industrial Economics | 3 |

| KH00BY85 | Workplace Communication | 3 |

| TE00CS24 | Calculus | 5 |

| 1001004 | English Professional Skills, B2 | 3 |

| TE00CB20 | Work Safety | 1 |

Operation Management Module (Choose all) |

15 | |

| TE00BL87 | Operations Management and Logistics | 5 |

| TE00BR47 | Basics of Technical Drawing | 5 |

| TE00BL88 | Costing and Bookkeeping | 5 |

Engineering Applied Skills Module (Choose all) |

15 | |

| TE00BM01 | Leadership and Management Systems | 5 |

| TE00CR79 | Management Accounting | 5 |

| TE00CK13 | Business Mathematics and Excel | 5 |

Supply Chain Management Module (Choose all) |

15 | |

| 5091164 | Product Data Management | 4 |

| TE00CP63 | Data Management and Analysis | 2 |

| TE00BS97 | Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) | 3 |

| TE00CJ50 | Supply Chain Management | 3 |

| TE00CQ24 | SUSTIS Sustainable development project | 3 |

COMPLEMENTARY COMPETENCE ENTITY (Choose ects: 150) |

150 | |

| TE00BL66 | Innovation Project | 10 |

| TE00CR76 | Team leader | 5 |

Technical Procurement Management Module (Choose all) |

15 | |

| TE00CR95 | Supplier Relations Management | 5 |

| 5091183 | Strategic Sourcing | 5 |

| 5091182 | Materials Management | 5 |

Technical Studies (Choose ects: 10) |

10 | |

PRODUCTION ENTITY (Choose ects: 30) |

30 | |

Production Management and LEAN Module (Choose all) |

15 | |

| 5091171 | Production Management with ERP | 5 |

| 5091172 | Process and Quality Management | 5 |

| TE00BX97 | Capacity planning and control | 5 |

| TE00CP48 | Product Development Management | 10 |

| 5091173 | International Business and Cultures | 5 |

PROFESSIONAL SALES ENTITY (Choose all) |

30 | |

Technical Sales Management Module (Choose all) |

15 | |

| 5091180 | Technical Sales Skills and Processes | 5 |

| 5091167 | Sales Workshops | 5 |

| 3041234 | Creativity and Innovativeness | 5 |

Business Development Module (Choose all) |

15 | |

| 3101108 | Customer Relationship Management Systems | 5 |

| 5091173 | International Business and Cultures | 5 |

| 1000414 | Project | 5 |

OPTIONAL STUDIES ENTITY (Choose ects: 30) |

30 | |

| TE00CQ15 | Introduction to Mathematical Sciences | 5 |

| TE00CS09 | Statistics | 3 |

| TE00CS04 | Brush up your Swedish language skills | 3 |

| 1000322 | German language 1 | 5 |

| 1000323 | German language 2 | 5 |

PRACTICAL TRAINING ENTITY (Choose all) |

30 | |

| 3101194 | Practical Training | 10 |

| 5091105 | Practical Training 1 | 10 |

| 5091106 | Practical Training 2 | 10 |

BACHELOR´S THESIS ENTITY (Choose all) |

20 | |

| TE00CY37 | Planning of the Bachelor’s Thesis A | 6 |

| KH00CY38 | Planning the Bachelor’s Thesis B | 4 |

| TE00CS20 | Report and Maturity Test | 10 |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank EU Erasmus+ Capacity Building finance for our project. We are most grateful to the fish farmers, hatchery operators, entrepreneurs, government officials, and other value chain actors who shared their precious time to talk to us about their experiences and stories.

References

Egesa, M., Lubyayi, L., Tukahebwa, E.M., Bagaya, B.S., Chalmers, I.W., Wilson, S., Hokke, C.H., Hoffmann, K.F., Dunne, D.W., Yazdanbakhsh, M., Labuda, L.A., & Cose, S. (2018). Schistosoma mansoni schistosomula antigens induce Th1/Proinflammatory cytokine responses. Parasite Immunol, 40, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/pim.12592

Gukelberger, E., Atiye, T., Mamo, J.A., Hoevenaars, K., Galiano, F., Figoli, A., Gabriele, B., Mancuso, R., Nakyewa, P., Akello, F., Otim, R., Mbilingi, B., Adhiambo, S.C., Lanta, D., Musambyah, M., & Hoinkis, J. (2020). Membrane bioreactor–treated domestic wastewater for sustainable reuse in the Lake Victoria region. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 16, 942–953. https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.4281

Hamilton, S.E., Gallo, S.M., Krach, N., Nyamweya, C.S., Okechi, J.K., Aura, C., Oragi, Z., Roberts, P., & Kaufman, L. (2019). The use of unmanned aircraft systems and high resolution satellite imagery to monitor tilapia fish-cage aquaculture expansion in Lake Victoria, Kenya. Bulletin of Marine Science, 96, 71–93. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2019.0063

Isyagi, A.N. (2007). The aquaculture potential of indigenous catfish (Clarias gariepinus) in the Lake Victoria Basin. University of Stirling, Uganda.

Jacobi, N. (2013). Examining the Potential of Fish Farming to Improve the Livelihoods of Farmers in the Lake Victoria Region, Kenya—Assessing the Impacts of Governmental Support. University Centre of the Westfjords, Iceland.

Kipkemboi, J., van Dam, A.A., Ikiara, M.M., & Denny, P. (2007). Integration of smallholder wetland aquaculture-agriculture systems (fingerponds) intoriparian farming systems on the shores of Lake Victoria, Kenya: economics and livelihoods. Geografical Journal, 173, 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2007.00246.x

Maithya, J.M., Kimenye, L.N., Mugivane, F.I., Ramisch, J.J., 2007. Profitability of agroforestry based soil fertility management technologies: the case of small holder food production in Western Kenya. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 76, 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-006-9062-6

Munguti, J.M., Liti, D.M., Waidbacher, H., Straif, M., & Zollitsch, W. (2006). Proximate composition of selected potential feedstuffs for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus Linnaeus) production in Kenya. Bodenkultur, 57, 131–141.

Musinguzi, L., Lugya, J., Rwezawula, P., Kamya, A., Nuwahereza, C., Halafo, J.,Kamondo, S., Njaya, F., Aura, C., Shoko, A.P., Osinde, R., Natugonza, V., & Ogutu-Ohwayo, R. (2019). The extent of cage aquaculture, adherence to best practices and reflections for sustainable aquaculture on African inland waters. Journal of Great Lakes Res.earch, 45, 1340–1347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2019.09.011

Mwanja, W.W., Akol, A., Abubaker, L., Mwanja, M., Msuku, S.B., & Bugenyi, F. (2007). Status and impact of rural aquaculture practice on Lake Victoria basin wetlands. African Journal of Ecology, 45, 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00691.x

Mwanja, W.W., & Nyandat, B. (2013). Challenges and issues facing small-scale producers: perspectives from Eastern Africa, in: Bondad-Reantaso, M.G., Subasinghe, R.P. (Eds.), Enhancing the Contribution of Small-Scale Aquaculture to Food Security, Poverty Alleviation and Socio-Economic Development: Report and Proceedings of an Expert Workshop. FAO, pp. 107–115.

Namulawa, V.T., Mutiga, S., Musimbi, F., Akello, S., Ngángá, F., Kago, L., Kyallo, M.,Harvey, J., & Ghimire, S. (2020). Assessment of fungal contamination in fish feed from the Lake Victoria Basin, Uganda. Toxins, 12, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12040233

Njiru, J.M., Aura, C.M., & Okechi, J.K. (2019). Cage fish culture in Lake Victoria: A boon or a disaster in waiting? Fisheries Management and Ecology, 26, 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/fme.12283

Opiyo, M.A., Marijani, E., Muendo, P., Odede, R., Leschen, W., & Charo-Karisa, H. (2018). A review of aquaculture production and health management practices of farmed fish in Kenya. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 6, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijvsm.2018.07.001

Rutaisire, J., Char-Karisa, C., Shoko, A., & Nyandat, B. (2010). Aquaculture for increased fish production in East Africa. African Journal of Tropical Hydrobiologi and Fisheries, 12. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajthf.v12i1.57379

Ssegane, H., Tollner, E.W., Veverica, K., 2012. Geospatial modeling of site suitability for pond-based Tilapia and Clarias farming in Uganda. J. Appl. Aquac. 24, 147– 169. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454438.2012.663695.

Tibihika, P.D., Curto, M., Alemayehu, E., Waidbacher, H., Masembe, C., Akoll, P., & Meimberg, H. (2020). Molecular genetic diversity and differentiation of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus, L. 1758) in East African natural and stocked populations. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 20, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-020-1583-0

Walakira, J K Hang’ombe, B M Mugimba, K K Sserwada, M., Mwansa, S., Kakwasha,K., & Chimatiro, S. (2018). Fish trade in Africa and its implication to aquatic biosecurity in the Great Lakes region, Sixth International Conference of the Pan African Fish and Fisheries Association (PAFFA6). PAFFA, Mangochi, Malawi.

Publication references

Publication name: Overview of Educational Needs and Next Steps for Kenya`s Fish Farming Sector: An Educational Approach

Author:

Jari Hietaranta, Senior Advisor, Turku University of Applied Sciences

Publisher: Turku University of Applied Sciences / Talk Reports 4

Publication year: 2026

ISBN: 978-952-216-904-4

ISSN: 2984-4193

URN: URN:NBN:fi-fe202601154157