Usein hankkeiden elinkaaret päättyvät varsin pian loppuraportin koostamisen jälkeen, vaikka hankkeissa olisi luotu hyödyllisiä ja moneen sovellukseen kelpaavia tuloksia ja…

Development activities and methods in universities of applied sciences

Preface

Turku University of Applied Sciences launched an English language degree programme leading to a Bachelor of Social Services degree in 2022. As our international students have progressed to the thesis phase in their studies, it has become evident that there is only a limited amount of methodological literature on working life-oriented development activities available in English. This is why we decided to translate a publication that can be used in the teaching of research and development methods at universities of applied sciences. This book is based on a Finnish publication from 2017 which was written by Kari Salonen, Sini Eloranta, Tiina Hautala and Sirppa Kinos. In addition to translating the original manuscript, we have made some small editing changes to the original publication.

In this book, we describe the contents of development activities and outline the key concepts related to them. In addition, we examine working life-oriented development activities as part of innovative higher education studies. The perspective is pedagogical and professional, because development is largely a process of learning in action. Development skills and innovativeness are increasingly important and valued professional qualifications in working life, especially for those with higher education degrees.

Participation in practical development activities and management require an overall understanding of development. Participating in development activities and leading one’s own development project especially requires a high degree of self leadership and good cooperation skills. Teaching should support the understanding of the development phases and the progress of the work towards results in dialogical or trialogical interaction with different actors. This is achieved by through collaborative discussions, planning and evaluations and, if necessary, by redirecting operations. Peer support, encounters between people and reciprocity promote the development of overall understanding.

In this book, we draw from a wide range of development literature on a broad range of topics, as well as some research literature. All in all, Finnish literature on development is still relatively young and even scarce, even though working life, for example, has been studied for decades. For some reason, the methodological nature of development activities in particular has received little attention. This may be due to a lack of interest among working life developers in describing the exact use of working methods and tools in the same way as research methods.

Conceptual ambiguity and interpretability pose their own challenges. From the perspective of understanding development activities as a whole, the challenge of understanding methods is that for others methodology is a form of research or project management. For others, the methods are more of a bundle of working methods that activate the participants, without a research-based approach or reflective use of the information produced in development. Similarly, there are differences in perspectives on the use of already produced information as part of development activities and their management. This book highlights one way of structuring development activities and related concepts.

We use development activities as an umbrella term for the following concepts: development projects, functional theses, research-based development activities, development work, development, work development, project development and project work. This is because the definition in the literature is rather fragmented and unstructured. In addition, there are no uniform practices in the use of concepts in different higher education institutions in the same way as research activities.

Several significant trends in the 21st-century workplace — such as flatter hierarchies, democratised decision-making and increased cooperation between management, employees and various stakeholders — also affect the approach to development.

This approach has gained strength throughout the first decades of 21st century and also work community training emphasises such approaches. In modern organisations, the approach favours bottom-up, expert- and customer-oriented development activities instead of development work led by the organisation’s management.

However, the concept of development activities can be considered a comprehensive umbrella concept for all the understanding, work, and description of activities that result in a new issue or change in operations. From this point of view, development activities include the methodological starting points, rules and commitments of development and these create a framework for practical development that guides them forward by those committed to the work.

At the beginning of the book, we briefly introduce the principles of innovation pedagogy and link them to the research, development and innovation activities of universities of applied sciences. After this, we examine participation, leadership and work communities from the perspective of development activities. Then we structure the methodological basis for development activities and highlight the differences between research, development activities and project development on a general level. We complement this with a presentation of research-based development activities with examples from working life, mainly relying on the work of our students. Finally, we describe the concrete work phases of development activities and the development methods suitable for them.

Although our examples mainly come from the development of welfare services, we hope that readers will find links with the development of other services or products as well. Each main chapter also contains an information window in which we have summarised the key contents of the chapter.

We would like to thank the authors of the original publication. Although time has passed, the content of the book is not outdated, but it provides excellent support for students in the field in writing their thesis.

Turku, 5.6.2025

Mira Lehti

Senior Lecturer

Health and well-being

Turku University of Applied Sciences

Kari Salonen

Principal Lecturer, DsocSci, MA

Health and well-being

Turku University of Applied Sciences

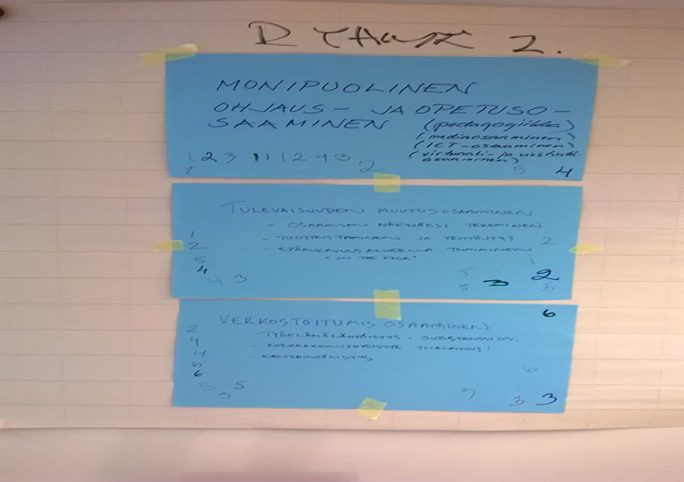

Image 1. In workshops, summary is an important stage.

1 Innovation pedagogy and development

This chapter briefly introduces the principles of innovation pedagogy and activities. Key elements include cooperation with partners from working life, authentic learning environments, and the promotion of students’ innovation competences.

The educational task of innovation pedagogy is to respond to changing working life needs. Its principle is to enable participants to collaborate to bring about change. These participants include students, representatives from working life, clients and teachers.

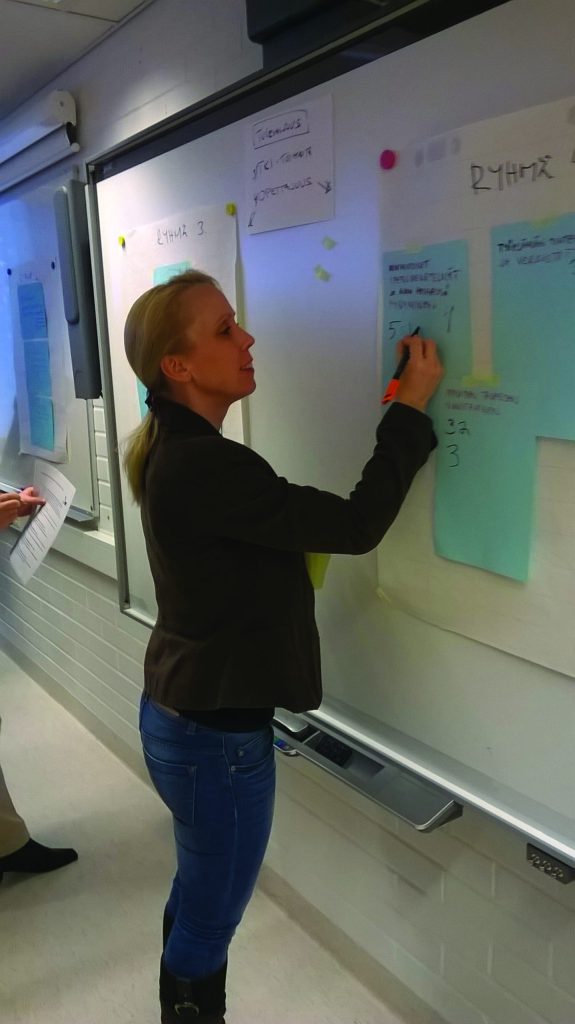

Image 2. Participatory workshops.

1.1 The basic ideas of innovation pedagogy

Development competence is increasingly important in the changing field of working life. In this period of change, employees are required to have a high level of know-how and an understanding of factors that enable the development of working life and the creation of innovations. Changes require employees, work communities, organisations and management to follow the principles of continuous improvement. At the same time, the importance of customer-oriented thinking, cooperation and networking has been emphasised. Universities of applied sciences have developed innovation pedagogy to respond to current challenges in working life and to strengthen the competence of future employees.

Innovation pedagogy links the activities of universities of applied sciences to regional knowledge and innovation networks. Multidisciplinary education in accordance with innovation pedagogy is linked to applied research and development activities, which support regional development and the emergence of innovations in working life (Kettunen, 2009).

The key elements of innovation pedagogy are learning and teaching methods suitable for universities of applied sciences, cooperation with working and professional life and innovations. Innovations can be product and service innovations, technology innovations, design innovations, marketing innovations, distribution innovations, process and cultural innovations or strategy innovations (Solatie & Mäkeläinen, 2009, 30–37). Innovation pedagogy is based on a constructivist concept of learning. In it, the learner’s own activities and processes of building new meanings serve as the basis for learning. Through diverse and working life-oriented learning environments, learners are brought into situations where there is an opportunity for new insights and practical development (Penttilä et al., 2009, 10–14) .

Turku University of Applied Sciences, together with a few other higher education institutions, has developed tools for measuring innovation competences. Measurement can be used to assess the development of students’’ competence needed to create innovations and, based on the assessment, to support the process if necessary. The areas of innovation competence include creative problem-solving skills, holistic understanding, goal-orientation, cooperation and networking skills (Räsänen, 2014; also Mulder, 2017).

In practice, innovation pedagogy and innovation competences combine the processes of producing and learning new knowledge. Learning through genuine working life cooperation and development projects is essential. In these situations, representatives from professional life, teachers and students act as equal developers, researchers and actors (Salonen et al., 2015). It is therefore important that students are attached to working life-oriented projects during their education, in which the production of new knowledge is practiced in practical activities with guidance. This ensures the development of the student’s professional competence and strengthens regional development.

Working life oriented development projects to which students are attached often take place in multidisciplinary teams. The teams define and specify the development task, carry out the necessary information search, exchange their expertise, implement the project and complete it. From the point of view of education, the key task of innovation pedagogy is to strengthen the students’ innovation capacity by combining teaching, research and development work and cooperation with working life actors. Innovation capacity refers to individual, community and network level competence. Students are expected to have creative problem-solving skills, holistic and contextual thinking, goal-orientation and the ability to work in various cooperation networks (Räsänen, 2014, 6-9). The strength of the approach is explained by a teacher below:

The starting points for networked development activities were the extensive utilisation of the knowledge capital of students, higher education institutions and working life. The members of the network contributed to the project, but also learned as they worked on the project. Utilising the different views and experiences of the working group members ensured the success of the project and the successful implementation of the developed activities into practical work.

Sini Eloranta, teacher, Turku University of Applied Sciences

1.2 Opportunities for innovation in universities of applied sciences

Degrees from universities of applied sciences are based on researched knowledge and professional practices. They also include research, development and innovation (RDI) skills as well as project management skills. These are particularly emphasised in master’s degrees at universities of applied sciences.(1) The aim is that education is future-oriented and proactive in terms of its content and teaching methods. Strong cooperation between teachers and students in working life forms the basis of the activities. A strong working life orientation must be included in all RDI activities. This requires education providers to have close and well-functioning cooperation networks through which development targets are identified and defined together in the networks. Students are active in their own development work in these networks. This is expressed in the student quote below:

I believe that project experience will be very useful in the future.

Rasmus Rantanen, engineering student, Turku University of Applied Sciences

(1) In the current development activities, the emphasis is on network-based work. This can also be called a tripartite working model (Nurminen et al. 2015). The model combines working life-oriented teaching, cooperation between higher education institutions and cross-sectoral, interprofessional work. The model has been developed especially in the Health and Welfare Division of Turku University of Applied Sciences. In development activities, the financier can also be seen as a fourth party. In this case, the tripartite system expands into a quadrilateral model.

Figure 1. Integration elements of research, development and innovation (RDI).

The RDI activities of universities of applied sciences require connections to working life, cooperation and the identification of the development needs of working life (Figure 1). RDI activities must also be integrated into courses and/or modules. This contributes to the wider recognition and recognition of degrees and education. In addition to the elements highlighted in Figure 1, the financier’s perspective is important in RDI activities when the development project is funded by an external party.

The RDI activities of universities of applied sciences are increasingly linked to various professional cooperation networks with a lot of expertise. These networks can be regional, national and international. Professional know-how and experience can be found in abundance outside higher education institutions, in workplaces and from their partners, as well as from customers and other actors. This expertise is increasingly utilised in development activities.

In innovative development activities, the relationship between formal and informal skills is changing. The aim of the education is both formal and informal learning (Palonen et al., 2013). In this case, the nature of education is innovative rather than repetitive. Structural and pedagogical changes that support the combination of formal and practical education have been proposed as a solution. At its best, development is just that (Penttilä et al., 2009, 10–14).

The role of a university of applied sciences student emphasises responsibility, independence and research and development skills. The task of teachers and working life partners (e.g. mentors, or project groups) is to integrate learning into RDI activities. This is based on the needs of working life, the subject matter of the degree, as well as personal competences and working life qualifications. In projects, the roles of customers (end users) and other participants may vary, but their input may be decisive for the result.

The customer perspective and expertise through experience play an increasingly important role in development activities, regardless of the industry. Organisations need methodological expertise and tools, the use of which is based on understanding the customer’s living environment, needs and views. This is also referred to as design thinking (e.g. Chase, 2017), which combines the above-mentioned aspects with experimentation and testing. This also sums up one of the core of development activities. (2)

In conclusion, the overall understanding and management of development activities are an important part of professional qualifications and personal competence competences, regardless of the industry. In higher education studies, development skills are strengthened when the studies are carried out in accordance with innovation pedagogy in genuine cooperation with working life as part of regional knowledge and innovation networks.

2 Participation and leadership in development

There are a few things that stand out above all others when starting development activities: an identified need for development, a jointly formulated goal, participation and leadership. Without these, we cannot really talk about development, as practical work in work communities is largely built on them, regardless of the industry.

In this chapter, we focus on participation and leadership as part of innovative development activities in work communities. We complement the perspective with the characteristics of an innovative work community and emphasise the importance of customer understanding. From the perspective of student learning, we want to emphasise leadership skills, project or development leadership, as part of innovative development activities.

Image 3. Combining recorded ideas in groups.

2.1 Customer involvement

Organisations and work communities exist for their customers, who are the source of their purpose and reason for being. In the 2000s, many organisations have developed their operations in a more customer-oriented direction to better meet people’s different and changing needs.

A customer orientation or customer proximity has many definitions. It can be approached from the perspective of both the interests of the organisation and the customer. From the organisation’s point of view, a customer orientation is about goal-oriented operations in accordance with the organisation’s basic mission. From the customer’s point of view, it is about responding to an individual need. A customer orientation also emphasises people’s ability to participate in their own service and the assessment of service needs, as well as to influence decision-making concerning their own situation. The customer orientation has increasingly extended to include customer involvement in the development of operations (Virtanen et al., 2011; Virtanen & Stenvall, 2012).

Many organisations have long collected customer feedback to support the development of operations. The obligation to listen to the customer’s views is enshrined in legislation (e.g. the Health Care Act 2010 and the Social Welfare Act 2014) and quality systems in companies. The opportunity to give feedback is one form of customer participation in development (Lundgrén-Laine et al., 2015). In addition to giving feedback, customers are also increasingly seen as development partners. For example, a the 2016 report “Smart experimentation and development in municipalities” found that Finnish municipalities had seen good results in customer participation in development work. Management plays a key role in strengthening customer understanding and implementing customer-oriented operations (Larjovuori et al., 2012).

Customers, residents, users and other actors can be taken into account even before new projects are implemented. On its website, the National Institute for Health and Welfare presents the tools for human impact assessment (IVA, ihmisiin kohdistuvien vaikutusten arviointi) and child impact assessment (LAVA, lapsivaikutusten arviointi). It is a process of assessing the effects of a decision on the health and well-being of children, families with children and other groups of people in advance. The focus of the assessment can be on a project, a plan or any decision. The aim of the evaluation is to provide information for municipal decision-makers, for instance (THL, 2017). (3)

Organisations look different when viewed from the outside. Clients usually have different knowledge than professionals. Therefore, exchanging experiences and views together with customers helps to deliver services that better meet their needs. It is important to ask customers for their opinions, actively involve them in development activities and, above all, develop structures and operating methods that enable customer participation. It is essential to consider what kind of customer involvement would best suit the development of the organisation’s operations. They should also be boldly tested to strengthen customer insight.

Over the past decade, more attention has been paid to taking customer data—i.e. their experiences and views—into account in the planning and implementation of services. In the public sector, this type of thinking is still largely budding and experimental, but the situation is likely to change in the 2020s. Hyysalo (2006: 8-10) aptly described companies already ten years ago by stating that the greatest strength in refining and developing services is to combine user, customer and market information. He also saw collaboration with customers and users as the greatest underutilised potential.

Another perspective in service development takes a more holistic view than just the user. It considers customers’ entire life situations, their service usage, and the expertise they have gained from these experiences. According to Kostiainen et al. (2014), experiential expertise includes many dimensions, such as personal empowerment and positive impacts. From the perspective of service production and organisation, the promotion of needs-based and productive services and the importance of peer support alongside professional activities are emphasised. For this reason, expertise through experience will play a key role in the development of the service system and in the planning, implementation and evaluation of service content in the near future. By listening to experts through experience, employees can better understand expectations regarding customer relationships, service content, interaction and the functionality of the system, and thus identify areas for development (Hietala & Rissanen, 2015).

(3) The Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) is an independent state-owned expert and research institute that promotes the welfare, health and safety of the population. THL’s duties are established in the Finnish legislation. Our key duty is to carry out research and expert work to prevent illnesses and social problems develop the welfare society support the social welfare and health care system and the social security system. (THL 2025.)

2.2 Competence of the work community in development activities

Over the past twenty years, globalisation, information and communication technology, the growth of knowledge and know-how, and competition have led to more attention being paid to the activities of individuals, the innovativeness of networks and the new kind of leadership described above. Without these, there can be no innovative development activities (Ståhle et al., 2004, 9; Punta-Saastamoinen, 2015).

Innovativeness is now understood as a practical activity in work communities that starts from a need and new ideas, includes output and creates new value. Value is not necessarily material. Innovations are always social in nature, based on cognitive and creative thinking, which is transformed into innovation only through cooperation between individuals. This cooperation, in turn, is based on organisational learning and proactive and self-directed activities (Senge, 1997, 298–300; Ståhle et al., 2004, 11–13; Moisanen, 2015, 4-7).

Management takes place in innovation environments at different levels. These environments include the level of structures and institutions, the level of organisations, and the level of individuals. In addition to these, from the management point of view, the network level can also be distinguished (e.g. Sydänmaalakka, 2012). Innovation environments include an innovation system, which guarantees the production of useful knowledge within the structures for use in development activities. In addition, the innovation system includes actors (e.g. managers, supervisors, employees, customers) and the interactions between these actors (Ståhle et al., 2004, 14). In other words, innovation and development do not rely solely on structural levels. That is why the innovation system is referred to as the “living backbone” of the organisation.

Based on what has been described, an innovative work community can be seen in development activities as a force that holds innovation environments and systems together, a primus engine, without which development cannot be achieved. Development also does not progress from creative ideas to value-adding activities without leadership. This requires sharing, discussing, engaging and listening. It is about the responsiveness of a learning organisation at all levels. It is a visionary, knowledge- and experience-based activity in which all employees work together to create a framework and processes that support the set goals. In other words, there has been a shift from management and government management to leadership of people and processes (e.g. Sistare et al., 2009). From the perspective of leadership activities, the leader’s own self-knowledge, vision of the future, communication skills and a strong relationship of trust between different actors are important (e.g. Sydänmaalakka, 2012).

In development activities, the management of work communities and networks does not rely on strict control, formal authority, rigid roles, individual expertise, or one-way communication. (e.g. Isoherranen, 2012, 60–63). One might ask, how a leader uses enough influence to achieve the vision. There is no single answer to this question. However, this can be viewed from different angles.

From an innovation perspective, effective network collaboration requires core work groups to have the means to exert influence. It is about enabling action, not slowing it down. Ståhle et al. (2004: 32–50) divide enabling innovation in work communities into four areas: structures, knowledge and interpretation, energisation and competence development (also Tahvanainen, 2010).

Structures are enablers of development activities, which can include legislation, management and decision-making systems, the way operations are organised, the innovation system and the people and parties operating in it, as well as the relationships between these actors. The focus is on leaders and core groups, which can be supplemented in an appropriate way, for example, from the perspectives of competence or working in networks. Structures should be clear, although this is rarely the case in the real world. In practice, structures contain complex and invisible “subsystems”, so it can be difficult to get an overall picture. In addition, multidirectional interests (political, economic, confidential, product-specific, vested, etc.) have been “baked in” into the structures, which act as glass ceilings for development. However, these types of organisations do not meet the characteristics of an innovative work community in the 2020s.

Information and interpretations are important in development activities and innovation environments. According to this, the actors form numerous interpretations (language, meaning) of reality based on experience and other knowledge, which is slightly different for each participant. According to Ståhle et al. (2004, 35–36), what matters is how knowledge is transferred between actors and how it is transferred from the individual level to the collective level and vice versa.

Knowledge, interpretation, meanings and experience create a common language in an innovation system. This can be seen as a framework for understanding what, why and how operations should be developed. Reconciling interpretations and understanding is challenging in the management of development activities, because this requires an open attitude towards ideas, and a vision for the future. We should therefore be sufficiently open at the same time, but at the same time decisive. Leadership speech and the positioning of the leader play a central role in innovation environments and cooperation networks (e.g. Salminen, 2014; Nissinen et al., 2015).

The driving force of development activities, energisation, refers to activities that activate actors and strengthen their ability to respond to the challenges of a changing operating environment (Ståhle et al., 2004, 45). This is largely a question of respecting the competence of the actors, personal performance, encouragement, opportunities to advance in their careers, challenges and mutual trust. The situation resembles a kind of flow state in work communities (e.g. Järvilehto, 2012).

Development activities also include competence-based knowhow (e.g. Hätönen, 2011). According to Räsänen et al. (2014, 5-7), this can include, motives, character traits, self-concepts, attitudes, values, knowledge, and practical and cognitive skills. These can be evaluated at the individual, work community and organisational levels. Competencies usually need to be seen in relation to the environment in which individuals operate, so they are also context-specific. From the point of view of innovations, creative problem-solving skills, a holistic way of thinking and orientation to things, goal-orientation, the ability to cooperate in case and interpersonal networks are important (Sorsa et al., 2015).

Competencies can be core competencies or other competencies, depending on how they are defined in different organisations. However, it is important to identify competencies in development networks. These provide development activities with capabilities that they alone cannot produce or do not exist at all in the organisation. In addition to the above, institutional (structure, systems, relatively permanent operating models), procedural (action, management, competence, learning) and substantive competencies (knowledge, experience, specific expertise) can be distinguished in innovation environments and development networks (Ståhle et al., 2004, 53; Isoherranen, 2012, 65–66).

2.3 Characteristics of an inclusive and participatory work community

The literature on development and management emphasises the inclusive and participatory approach of work communities (e.g. Punta-Saastamoinen, 2015). Looking at it more broadly, it is a change in the management paradigm. The direction is clearly towards communal, deliberative and democratic dialogue (e.g. Uusitalo, 2012). In addition, managerial roles are shifting from formal and hierarchical positions towards collaborative leadership. This is particularly evident in organisations and work communities where development is vital for the continuation of operations in competitive situations and rapidly changing operating environments.

Another aspect of change is that even good managers need competent personnel for development activities (e.g. Hannonen & Leinonen, 2015). Increasingly, development competencies are not directly linked to a specific position or job description in organisations, but development activities concern all employees in work communities. The third aspect relates to knowledge, which is a critical part of the intellectual capital of organisations. According to this, knowledge of development is not the property of a few, but must be shared communally. In this way, new kinds of leadership, participation and cumulative knowledge together form an important functional infrastructure in development activities.

From the perspectives of participation and cohesion, development activities can emphasise common interest (interest), uniqueness and excellence (identity), belonging to a group (communality), confidential and open discussion (reciprocity), purposeful and goal-oriented work (goal-orientation) and the place or space (encounter) where practical work takes place (e.g. Seppänen, 2016).

The characteristics presented apply to all innovative organisations and work communities. Virtanen et al. (2011, 45–48) see a new kind of organisational culture based on a customer-oriented way of working as a solution for service organisations. All employees play a key role in this change and in developing the culture. However, special emphasis is placed on leadership and leaders. Leadership roles and the room for manoeuvre included in the position must focus on increasing equal interaction, encouragement, encouragement, enabling renewal and utilising new ways of working. All of these are also emphasised in innovative development activities.

The emergence of a new, participatory culture in development activities requires an innovation process that takes place both “top-down” and “bottom-up” and strengthens customer proximity (e.g. Punta-Saastamoinen, 2015). This applies to public, private and third sector operators alike. The driving force is proactive and contextual work, where the view of the future transcends the individual organisation. This type of innovative work often involves small-scale, problem-solving and gradual development (incrementalism). However, this does not preclude more holistic (holism; ecosystems) and fast-paced development, as the two approaches can be present simultaneously interleaved and nested (e.g. Senge, 1997, 12–16). What is crucial are changes in operating environments and the development requirements that come from them, to which the different actors in the organisations respond through cooperation.

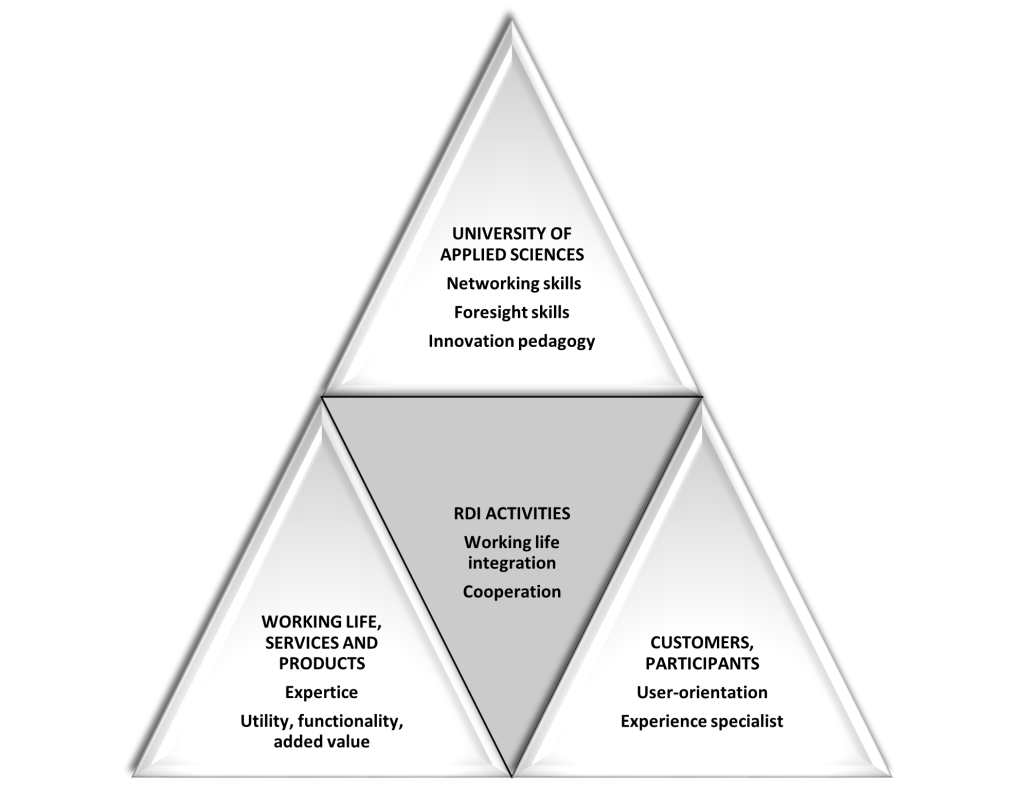

In a summary on the future of work, Kurki et al. (2014, 126–127) illustrate the roles of employees, work communities and supervisors, as well as the mechanisms for creating innovations (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The mechanisms of innovation and their characteristics (Kurki et al. 2014, 126 I paraphrase Fuglsang and Sörenssen 2011).

In the example, Bricolage is an activity in which challenges identified in everyday work are sought together for functional solutions. The bricolage approach does not always include systematic development work, but the starting point is situation-orientation and the most suitable solutions or improvement proposals (e.g. Cantliff & Thompson, 2016). The active actor here is the employee(s). Bricolage emphasises a kind of common sense in dilemmas. Innovation supported by the supervisor emphasises the common definition of the problem area and the prioritisation of solution options collectively. The third perspective emphasises the role of the supervisor, where the management together takes development activities forward. In all these perspectives, regardless of the levels of examination, communality and participation are emphasised.

A key issue in innovative development activities and at the same time a challenge for professional competence is the building of dialogue, i.e. dialogue and mutual understanding in work communities (e.g. Uusitalo, 2012; Piippo et al. 2014). Syvänen et al. (2014, 326–328) see reciprocity, learning, intrinsic motivation, and leadership that fosters creativity as key to creating the clearest possible consensus. According to them, management that emphasises innovation identifies and values the individual needs of employees, which through participation are channelled into the benefit and driving force of the work community. One of students explains this concept:

Rarely, in a development project do you get to choose the people with whom the development work will be carried out. This is where cooperation and interaction skills come into focus. You need to be able to understand individuals from different backgrounds, temperaments and personalities in order to promote smooth, goal-oriented and inspiring work through your own interaction. This requires good self-knowledge and understanding of interpersonal activities. Success largely depends on how successful you are in leading the success of others.

Päivi Kaisti, Master’s degree student in Social Services, Turku University of Applied Sciences

2.4 Organisational management and innovation

The management of organisations, whether public, private or third-sector, has become a challenging area of professional competence, especially in the 2000s, from the perspectives of globalisation, ownership, changing operating environments, politics, economic space and competition, as well as personnel competence. At the core of management is the development of organisations in competitive situations. It also seems that development activities cannot be seen as just another side effect of management as part of planning, decision-making or finances, as before, but as an essential part of the overall operations of organisations. Self-management has become a key issue—whether it concerns leadership competence that takes place in organisations or is created in education (Sydänmaalakka, 2012). (4)

Following the development stages of various organisations, Laitinen et al. (2014, 90–91) state that current innovation theories emphasise the need for continuous renewal. The existence and success of organisations depend on their ability to develop new services, products and ways of working, often with other organisations. What is important here is the experience and knowledge gained through development activities and the utilisation of these in the work.

This also means a change in the characteristics of organisations. Permanent structures, processes and operating methods have been replaced by interactive and change-responsive functions. Guided by innovation qualifications, the organisation itself may also require competencies from the management that are not tied to time, place, or task (e.g. Trias de Bes & Kotler, 2015). This change includes surprising operating environments, motivating and encouraging employees, creating conditions that enable renewal, acknowledging the limitations of rational action, and non-linear development of organisations (Heikkilä et al., 2015; Pauleen & Gorman, 2016).

The above puts the management of organisations in situations where only reflective, creative, listening, participatory, sharing, encouraging, engaging and systematic leadership can lead to sustainable development activities. However, this does not mean that management should include all the elements mentioned, but their complete absence will eventually lead to the withering or disappearance of the organisation, especially in competitive situations. As a rule, the main thing is not the manager’s organisational position, power or formal education, but his personal competence (capability), motivation, experience and desire to lead development activities.

The most important message of the current management literature and research to organisations and work communities is that leadership is an integral part of creating and maintaining a culture that supports development activities. Juuti (2005, 20–21) stated already a decade ago that the creativity and innovativeness of organisations must be placed at the centre of management analysis. By creativity he means creating new concepts, thinking and operating methods, while innovation management aims at their introduction and implementation in work communities.

Innovativeness is built in strangeness, distortion and unpredictability. It does not always respect organisational positions, power relations or the skills written in job descriptions. In expert organisations where creativity and innovation are built on interpersonal networks, well-functioning personnel chemistry and an atmosphere conducive to creativity, leadership is largely based on visionary leadership. In this case, the organisational culture is permissive, supportive, learning and reflective (e.g. Senge, 1997). From the perspective of development activities, management activities are both horizontally and vertically networked. According to this, key cooperation relationships and environments play an important role in management.

However, it is not enough to examine management alone in development activities; it is a complex and multi-level phenomenon. Aalto (2005, 82–84) lists several elements that support innovation, with which an organisation demonstrates its own capabilities. These include participatory leadership, a clear and interactive communication system, allocation and availability of available material and intellectual resources, functional physical environments, reduction of hierarchy and bureaucracy, a reward system that supports development activities and innovation, and the organisation’s own goals (e.g. Naaranoja & Heikkilä, 2015). Understood in this way, almost all other work community activities, development and innovation can logically be derived from the management of organisations. Leadership competence is about a high level of professionalism, encouragement, commitment and the reconciliation of values both in written strategies and in everyday work (Sorsa et al., 2015).

Leadership in development activities also gives rise to a number of different roles (e.g. Ristikangas et al., 2015; Sankelo & Heikkilä, 2015, 188–190). Leadership roles have been studied for decades, although in the last twenty years their most visible feature has been concentrated not only in self-leadership but also in pedagogical leadership. (5) According to Salmi et al. (2010, 82–84), leadership that supports groups creates independence, faith, strength, commitment, community and collaboration, as well as positive things related to group culture. Leadership roles include those of mentor, supporter, encourager, coach and listener, as Quinn (1988) once put it. These are still topical in organisational development activities. They are also very different from professional roles that strengthen organisational hierarchy and bureaucracy. This is described aptly by a student below:

Before working as a project manager in a development project, I had no management experience. Adapting to a completely new position was therefore reasonably challenging. However, I am more than happy that I had to step out of my comfort zone, which management itself was. However, I got over the initial uncertainty very quickly and I think that working as a project manager gave me a huge number of tools for possible future managerial work or, for example, project work. Above all, I learned to take responsibility for a fairly large process and to complete it in accordance with the objectives.

Kaisa Lamminen, Master’s Student in Development and Management, Turku University of Applied Sciences

(4) We are discussing management here on a general level because the current management research and literature is extensive. We recommend that you familiarise yourself with the literature to the extent that it is useful for professional competence and organisational development activities. Especially in master’s university education, management is a key part of teaching, regardless of the field of study. In addition, the training emphasises innovative leadership. Through this, new forms of leadership competence are created in cooperation in organisations, which can be considered an important competence in the changing and globalising working life.

(5) By this we mean leadership and practical leadership actions that are based on knowledge of being human and human actions and learning to understand. Defined in this way, pedagogical leadership is not tied to a specific field (e.g. early childhood education), but an understanding of people’s actions, motives, experiences, thinking and emotions that underly leadership.

3 On the methodology of development activities

The chapter discusses the background and starting points of the overall understanding of development activities. Our idea is that without mastering these issues, there can be no comprehensive understanding of development activities. This, in turn, has a direct impact on practical development activities.

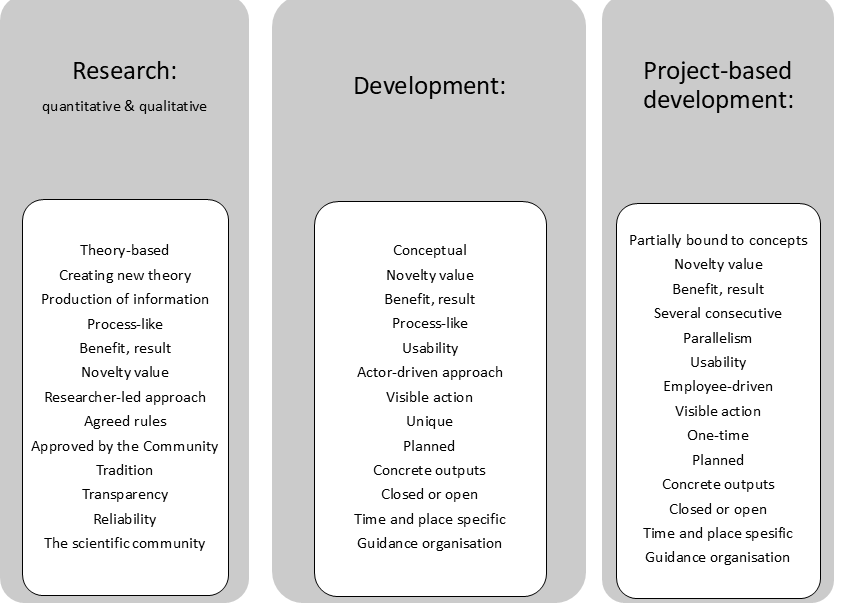

We start with the justifications for development activities. After that, we will briefly present the roles of a few research traditions in the context of development. Finally, we distinguish between research, development and project development (project work). In practical work, however, these overlap, so the distinction is partly theoretical.

Image 4. Written output of the workshop.

3.1 Background, perspectives and arguments

Development activities are based on an understanding of the target of development, the justifications and boundaries of the site, the goal of development, the development methods or tools to be used to solve the issues at the site, how to carry out an assessment, and the means and channels for disseminating the results.

Development must be based on understanding and commitment, as well as on the rules guiding the activities. According to this, development activities are based on the concept of knowledge, the production of knowledge and the interpretation of the results or outputs obtained. In practical work, this simply means that the participants must have as common an understanding as possible on the object of development and how it could best be understood, explained, reformed, improved or changed. The perception of the object is developed through a shared language and shared concepts, which, in turn, are grounded in an understanding of the overall methodological nature of development activities.

According to Hyötyläinen (2007, 364–365), in perceiving the overall nature, it is necessary to distinguish between the model world (language, concepts) and the real world (understandable reality, the world around people) and to understand the relationships between them. Complex relationships refer to how theories and concepts can be used to understand the object of development as a practical activity and, on the other hand, how the object of development can be used to explain, understand and create concepts, explanations and new (operational) models that describe it.

Development activities must take into account the worldview, perception of reality, conceptual framework, and development approach on which the practical work is based. In other words, they rest on certain fundamental premises and assumptions. However, methodological and theoretical-practical premises can be difficult to understand or control, as they simultaneously include both an understanding of reality and its nature and an understanding of the concepts that describe this reality (e.g. Räsänen, 2007, 54–55; Niemi-Kaija, 2014). Therefore, the objects of development and the related interpretations and solution attempts can be understood differently among the actors. Solutions are never exhaustive, but open to interpretation and “doing otherwise”.

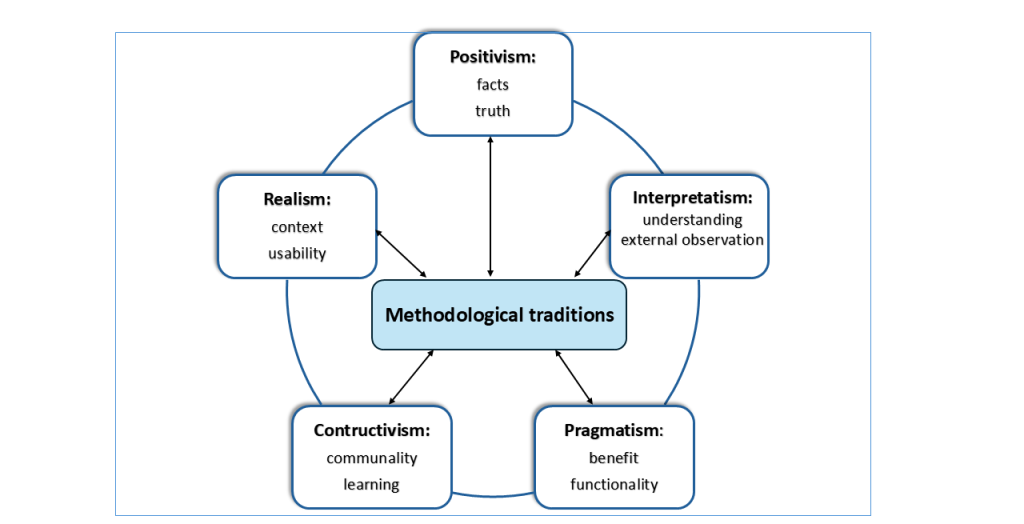

Hyötyläinen (2007) presents five development approaches: positivism, interpretivism, pragmatism, constructivism and realism. Approaches can be used to build a methodological understanding and overall management of development activities. Of the approaches mentioned here, pragmatism, constructivism and realism in particular are close to the development activities of universities of applied sciences.

Unlike other traditions, the positivist tradition is grounded in a worldview that presents the world as a set of facts and causal relationships, which empiricism seeks to explain. As such, this approach is difficult to apply to the research development activities of universities of applied sciences, so its place can be defined as an approach supporting development activities. However, in limited circumstances, the positivist approach has its own useful and supportive function. For example, before starting development, the baseline situation or experiences gained from new kinds of activities can be investigated with the help of a survey (Anttila, 2014).

Interpretivism emphasises social action, which aims to construct theories. Unlike the positivist tradition, the explanation models also include understanding people and an understanding approach. According to this approach, it is important to observe visible reality, the real world in which people live and operate. The role of the developer is participatory and observant, but according to the positivist tradition, “cool”, distant and objective (Hyötyläinen, 2007, 309–310). Defined in this way, the key task of development is to produce new information to support the desired changes.

The pragmatist tradition is based on the idea of pragmatism, where knowledge and work can be used to solve the challenges of working life in a planned and controlled manner. The information produced serves the participants from the perspective of benefit and functionality. This approach can include: action research, practice research and developmental work research (see chapter Research-based development of work), although these also have similarities to constructivism and the realist tradition (Keskitalo et al., 2016).

Pragmatism can also be understood as an attitude. It emphasises functionality, practicality and communality. For example, working life development activities are valued according to the benefits and impact they generate. Unlike positivism, this includes elements of human error, because certain and infallible knowledge can never be produced as the basis for development. The pragmatist understands the world and reality as a state where there is always room for different interpretations and corrective measures (Laitinen et al., 2014, 7-9; also Kilpinen et al., 2008).

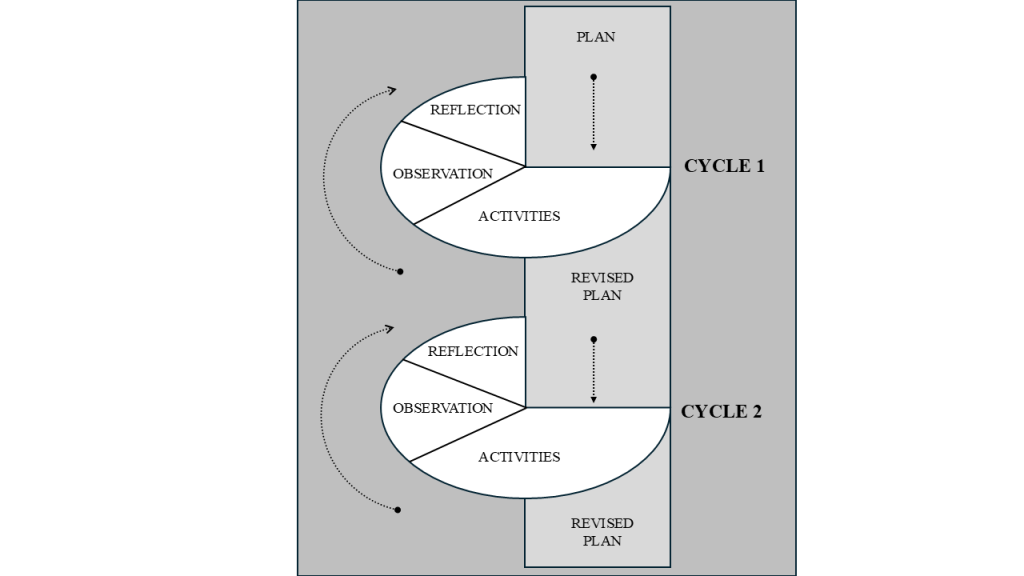

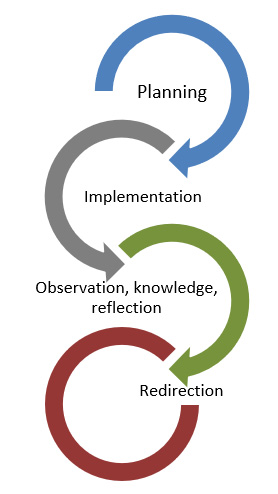

The constructivist tradition emphasises the cyclical nature of development (Figure 4) and the development process, in which, for example, developer workers participating in problem-solving work in work communities are full-fledged actors. Their task is to guide, direct and specify development targets and goals through development cycles, i.e. advanced phases, together with other participants in the work. It is a question of an equal approach to work and democratic dialogue, in which, in principle, no one’s knowledge or view is more important than others. Knowledge and understanding are built together through discussions, planning and experimentation (Smith, 2015).

Constructivism requires those involved in development to have clear goals that guide their work and as a comprehensive a picture as possible of the development targets and benefits to be obtained. This is based on a common language and jointly agreed working methods on how the development process should progress step by step and what the roles and tasks of each actor are. However, it is only through doing—through trial and error—that you will define what you want to achieve. From this point of view, the constructivist development approach includes an understanding of the close interaction between practical activities, participants and achievements, culminating in working together, a way of working that constantly corrects and evaluates oneself, and learning new things (e.g. Hyötyläinen, 2007, 373–374).

Following Deweyan thinking (Laitinen et al., 2014, 58–59), the above means that the individual becomes aware of their own thoughts and their functionality through various practical activities. Personal experience is at the core of learning, which requires the relationship between the individual and the environment, communication and reflectivity. This can be seen, for example, in development activities as a reflective working orientation. Thus, the individual learns, develops and develops through interaction with the surrounding community.

The realist tradition is close to both pragmatism and constructivism, and no clear line can be drawn between the two. The differences mainly occur in the emphasis of development activities. The approach emphasises the contextual nature of information, where the information and understanding produced are placed as clearly as possible in their own contexts. In addition, information must be functional and useful, in which case the information has an instrumental meaning, not one based on self-value (Anttila, 2007, 66–67). In accordance with the two previous approaches, development activities are about what kind of information is needed, how it is produced in interaction between people, and how information guides activities in achieving results and goals. In a realistic approach, the relevance and usefulness of information are ultimately assessed through the criteria of usability and practicality (Anttila, 2014).

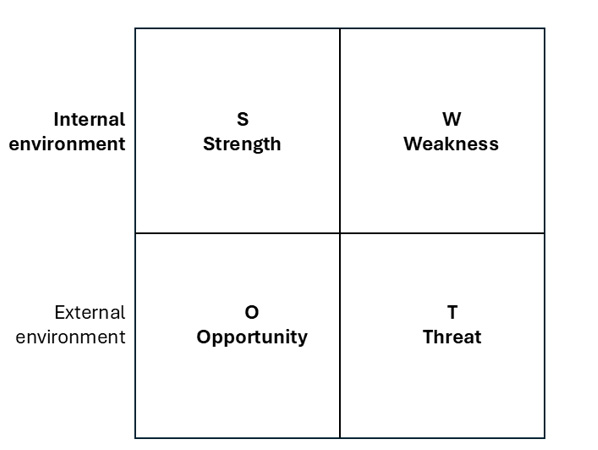

Figure 3. The linking of a few methodological traditions in development activities.

The relationship between the research, development and innovation (RDI) activities of universities of applied sciences and approaches can be summarised as follows. Development activities must be based on a vision of the development targets, needs, and goals formed together with representatives from working life, students and teachers. Development is based on knowledge that is produced and shared together. This creates a common language and concepts of development, which can also be called shared understanding and sharing meanings (e.g. Perttula, 2006). The principles of practical work in development activities, on the other hand, consist of participation, equality and a communal approach to work.

However, in research, development and innovation activities, doing things is not just about talking and formal participation, but this is guided by a systematic approach from the justification of the desired changes to the results or outputs. In this sense, the activities are rational, based on learning new things, managed and cyclically built from different work phases. In addition, the participants try to anticipate randomness and deviations together as well as possible. Self-assessment and a self-correcting, reorienting, iterative approach to work are also essential to the activities. This manifests itself in deepening cycles, where each new cycle is more precise than the previous one in line with the development target and objectives (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Cyclicality of development activities (Linturi 2003; Virtual University of Applied Sciences 2017).

3.2 Differences and similarities between development, research and project activities

Based on the above, a development approach can be defined as a working orientation that combines the philosophical premises of science (ontology, epistemology)(6), concepts, data collection methods, data analysis methods, interpretations and results or outputs, as well as systematic work carried out together with the participants. Development activities proceed cyclically as a process-like chain of actions, events and information (e.g. Räsänen, 2007, 44–47; Kananen, 2012, 25–28; Pohjola &; Koivisto, 2013, 90–92; Salonen, 2013).

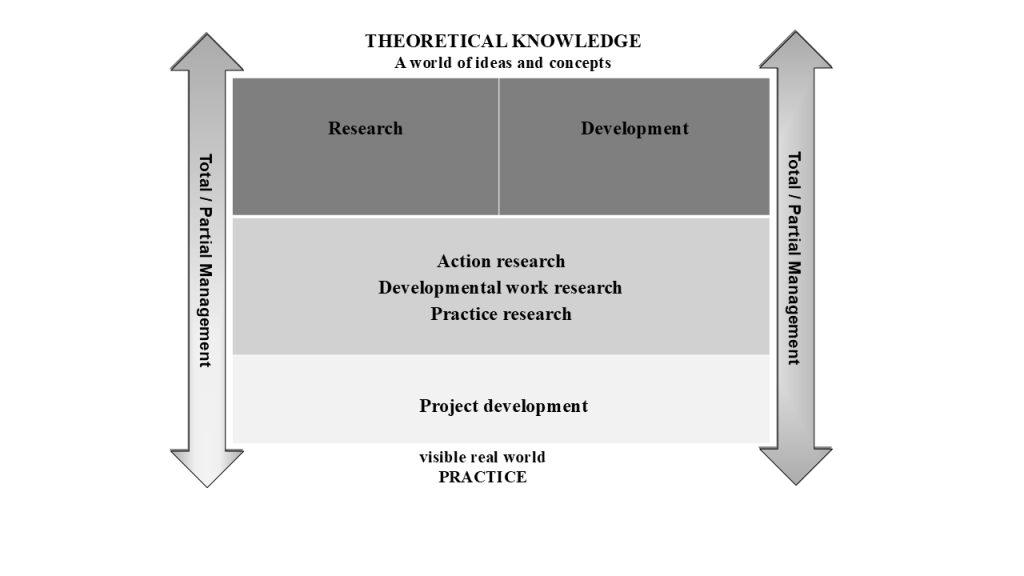

It is important to note that research and development activities involve different starting points. First of all, one of the basic premises of research is the pursuit of the production of new knowledge through scientific research methods. Research activities include classic, even centuries-old traditions and rules. The researcher produces something new in accordance with research ethical norms and scientific research methods (Figure 5). In addition, research and development activities can both be long-term or continuous activities in organisations.

In the case of development activities, the primary goal is typically to change a concrete state of affairs or activities. Development activities are context-specific activities that take place in time and place. In other words, they have their own limited, planned, phased and results-based task in a given environment. In addition, the work is guided by jointly agreed rules, procedures, language and concepts. From the perspective of learning and reworking, many features of innovation can be seen in development activities. They can utilise research-based methods, such as surveys, interviews or observation of data collection methods. The aim of these is to produce information relevant to the development project at hand. In addition to this, previous research data is also utilised in development activities. In action research approaches, there is an interface between research and development, which means that the same activity can be both research and development at the same time.

Figure 5 ideally attempts to distinguish between research activities and development activities from the perspective of development approaches to development by project.

Figure 5. Elements and levels of development activity.

Project development is practical development, renewal and improvement work clearly contextualised at time and place. Thus, it involves project work and activities. The organisation of project work is usually structured hierarchically in the same way as line organisations (so-called project management; e.g. Vaskimo, 2016), although other perspectives have also been presented especially in the management of complex projects (e.g. Alotaibi, 2016). The management of the starting points and entities of development can be considered “thinner” in development activities and research activities and more practice-oriented, performance-oriented, task- and/or result-oriented. It should be emphasised, however, that differences in practical development work may be minor.

Thus, project development (project work) is the work that designated project workers do in an organisation that has set the project as a one-time and deadline with goals, resources, and schedules. Project types include delivery and investment projects, development projects, and government projects. Synonyms for a project include: development project, development work, programme, pilot, experiment, reform, contract, etc. (e.g. Paasivaara et al., 2011).

Common characteristics of a project include:

- A project is always unique.

- It is limited in time and subject matter.

- Its objective is defined.

- It is designed.

- Designated workers complete the project.

- Work is a group activity.

- A new thing is developed during the project.

(Paasivaara et al., 2011).

The list can be supplemented with the characteristics of the project activities of welfare services, although similar features can be found in other projects as well. This can include the length of the time span, resourcing, planning, goal-orientation and timeliness of operations. From the perspective of competence, project management, teamwork, good interaction skills, content competence and experience in project work are emphasised. User-orientation, customer orientation or customer-centricity will also emerge as competitive advantages in the near future. The role of political guidance is also strong. This may include political decision-making, values, funding, burden-sharing issues and scrutiny (Paasivaara et al., 2011).

The development approaches described above can also be supplemented with the concept of renewal. This can be defined purely as an activity that improves and changes practices, where time and place are clearly defined (e.g. Bricolage method). Renewal does not require an overall conceptual understanding or mastery of the workers, knowledge of traditions, a participatory approach to work or step-by-step overall planning of operations. Instead, it can be localised into individual actions that bring limited but valuable benefits and improvements. However, it must be emphasised that even if the reform is only a single act or action, it can play an important role in the work community, for example. Therefore, not all development needs to be based on a broad and in-depth methodological understanding of the work.

Figure 6. Characteristics of research, development and project (paraphrased by Salonen, 2013).

4 Research-oriented development work

In this chapter, we briefly introduce research-oriented development activities. Understanding the tradition of research-based development work is important in activities where the working approaches of development and research are close to each other. These also concretise a holistic understanding of research work, but in such a way that working methods and approaches are development-oriented.

The guiding principles of research-oriented development activities include the benefits and functionality obtained, not just the information obtained through research. It emphasises pragmatism. We want to emphasise that all development approaches have a place in working life, whether it is pure research, research-based development or project-based development.

We present three approaches to research and development strategies: action research, developmental work research, and practice research. We will supplement these with practical examples.

Image 5. Analysis and recording of competence on the board.

4.1 Background to work development

At the beginning of the 1900s, simple and mechanical factory work and farming based on experience began to take a back seat and were replaced by a more complex, independent, but at the same time network-like ways of working (Engeström, 1995). This change in work and, at the same time, the development of qualitative research alongside the positivist research tradition contributed to the emergence of research-based methods for developing work. Among these, action research and developmental work research have a long history, while practice research is a more recent addition. They provide researchers and development workers with a clear process, conceptual system and concrete methods.

These different approaches have a lot in common, and drawing a line between them is not easy. In all of them, the researched knowledge is a tool for development. However, knowledge is not the end result of research, but a process in which knowledge is built through interaction between people. Information is collected at different stages of development, for example, by interviewing employees, videotaping operations or asking for experiences. Data is also analysed at many different stages of development. This gives an idea of the current situation of work, the need for development and the functionality of new ways of working. The criterion for the validity of knowledge is pragmatism, i.e. benefit (Heikkinen & Huttunen, 2010).

Work development approaches define the process of change in collaborative work as learning (Kiviniemi, 1999; Engeström, 2004; Satka et al., 2016), while change is striving towards something that does not yet exist. However, change is achieved through dialogue and reflection (Engeström, 2004, 61; Satka et al., 2016), while reflection is defined as considering and questioning things and ways of acting, and as interaction between the inner and outer worlds (Moilanen, 2001, 102).

The development of work must be carried out by those who do the work, use services or act as partners. No one can develop work alone, but employees have the right and duty to participate in implementing change. Without their involvement, the end result of development will not be reliable. The underlying view is that people are active, capable and capable. At its best, the development process empowers the participants (Heikkinen, 2010, 20; Satka et al., 2016). Individual participation can be guided and assisted by using activating and illustrative methods.

4.2 Action research

Action research has been defined, among other things, as “a systematic approach that aims to achieve new information through intervention, but also to test this acquired knowledge in practice and change practice with it” (Heikkinen, 2010, 41). In action research, data collection, data analysis and changes in work take place simultaneously. Development begins with joint planning by employees and possibly customers, which often involves mapping the history and current situation of the work. In this way, we seek an understanding of how the situation has come about and what the starting point for development is. In the communicative action research approach developed by the Swedish Gustavsen (1992), planning involves formulating concrete goals for change and defining the conditions for achieving them. Common goals and prerequisites guide development throughout the process.

On its smallest scale, action research is the development of one’s own work. But even then, development takes place in interaction with other actors. Action research is often used as a tool for developing the activities of a working group or team, but it can also focus on examining relationships between groups or developing the activities of an entire organisation (Heikkinen et al., 2010).

Action research is characterised by the cyclical progression of the change process (Figure 4). Planning is often used to create new operating methods or tools to be tested. The effectiveness of the new approach or instrument must be observed in order to gain an understanding of whether the change corresponds to the needs and objectives. Observations are carried out systematically using various data collection methods. Through observations, analysed information, experiences and joint reflection, operations are modified and improved. This starts a new cycle of development. The cycles continue until the development goals have been reached.

Example of action research development

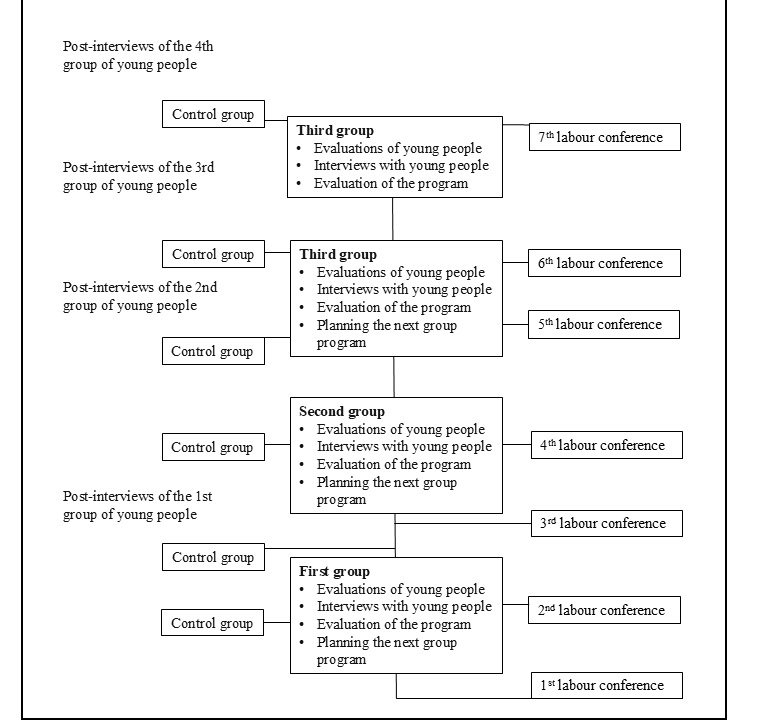

Turku Social Services launched a new kind of rehabilitation experiment, including psychiatric expertise, for young people at risk of social exclusion and who were difficult to employ. The rehabilitation was carried out in periods of 5-6 months, each of which involved 5-8 young people. The staff consisted of two instructors, both of whom had training and experience in the field of psychiatry. From the very beginning, a researcher was wanted on board, and action research was chosen as the research method, which was used to evaluate and develop the activities for two years (Hautala, 2009).

Development took place according to the principles of communicative action research over four cycles, i.e. four rehabilitation periods. Democratic dialogue was carried out, for example, at working conferences. The first, or kick-off, conference focused on what kind of rehabilitation activities would be most ideal and under what conditions such activities could be carried out. Respect for young people, creating an inspiring programme that serves young people, and support for young people in all areas of life were named as ideal goals. Appropriate and functional premises, financial resources, management support and the right customers were named as prerequisites for operations. These goals and conditions served as a mirror for future work conferences and as criteria for evaluating the quality of rehabilitation activities after each rehabilitation period and planning for the next period (Hautala, 2009).

Diverse information was collected during the development process (Figure 7). Participating young people’s experiences and opinions were surveyed by interviewing them at the end of the rehabilitation period and approximately six months after the end of the period. In addition, the functional capacity of the young people was measured at the beginning and end of the rehabilitation period using variety methods. A steering group had been set up for rehabilitation activities, whose members represented the different administrative municipalities whose services the young people used during the rehabilitation period. Notes and minutes of the meetings were part of the research material. At the end of the study, members of the steering group were also interviewed (Hautala, 2009).

Figure 7. Research progress (Hautala, 2009).

4.3 Developmental work research

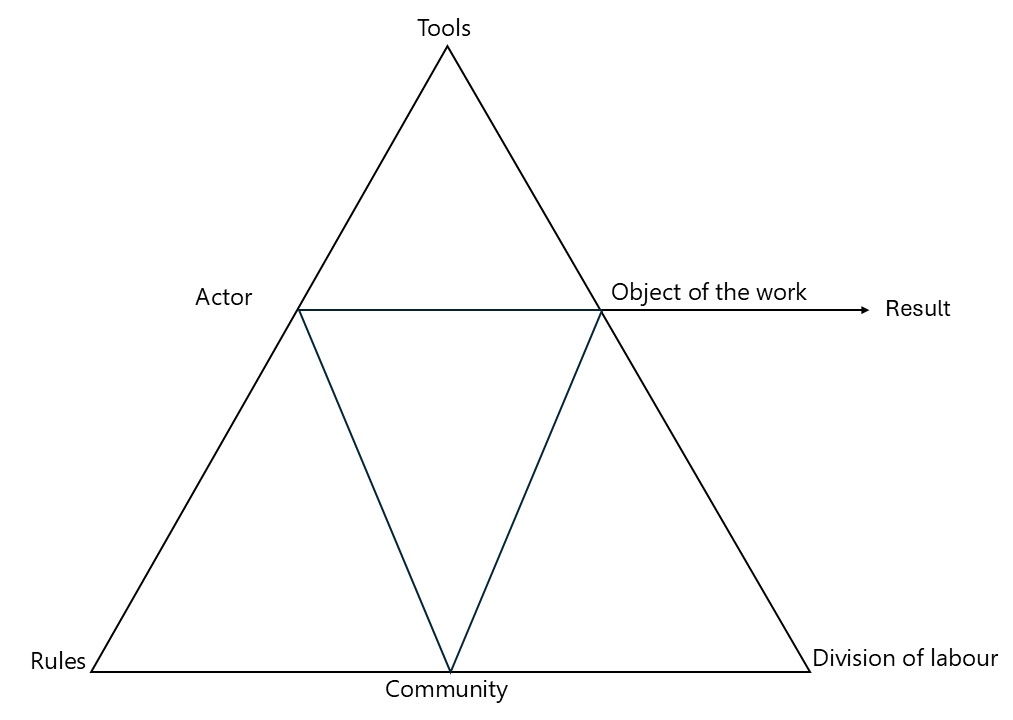

Finnish-origin developmental work research is grounded in cultural-historical activity theory, focusing on the development of organisations, their systems, and activities from within. In it, the mind of the individual can only be understood through the interaction between humans and the world. In this case, action is a tool for interaction, a kind of bridge between people and society. On the other hand, human actions and qualities are seen to be formed in a collective system of action, such as work. This is how cultural and social factors shape people (Engeström, 1995).

Drawing on cultural-historical activity theory, Engeström developed a comprehensive operating system as a tool for examining work (Figure 8), in which all elements are interconnected. That is why the operating system is constantly in motion, i.e. it is constantly changing and evolving. When an area changes, for example new rules or different instruments are introduced, the situation gives rise to conflicts and the need to change the entire operating system. Engeström (2004) has stated that conflicts are a source of strength for learning and a necessary characteristic of development.

Figure 8. General model of an operating system (Engeström, 1995).

The concepts of the operating system come from the theory of action. The object of the work refers to a theoretical concept, which refers to a thing or phenomenon with which actors interact and which they influence through their actions. In addition, it refers to the results and social significance of that influence. The object is defined by answering the questions of what is produced, to whom and why. Tools are things or objects that actors use to target an object. They can be concrete tools, devices and systems, but also different models, theories, concepts, and descriptions of operating methods and processes with which the object is processed and the result of the work is produced (Engeström, 1995).

The community consists of central, internal and external partners that an individual or team needs to carry out their work. The division of labour, on the one hand, refers to the position or power of the members of the community. It defines the division of labour between the working team (or other community) and what part of the object that team produces in relation to other actors in the organisation and external partners. Rules, on the other hand, are agreements, norms, guidelines and obligations, both written and unwritten, that guide the work (Engeström, 1995; Isoherranen, 2012).

The model of the management system makes it possible to examine the factors affecting work and the relationships between them. It can also be used to identify and concretise conflicts that prove to be the starting point for work development. For example, the new Act on Services for the Elderly meant that the old tools, such as working methods and the skills of the workers, were no longer sufficient. New operating models had to be developed, training for workers had to be organised and probably also the division of labour had to be reformed.

Developmental work research emphasises learning as a prerequisite for the process of change in work. The object of learning is the entire operating system and its qualitative change. Thus, learning is collective and long-term in nature. The concept of expansive learning is used to describe the learning cycle and the learning actions it contains (Figure 9). Learning actions take place through dialogue. Therefore, the presence of different points of view is allowed and even desirable (Engeström, 2004).

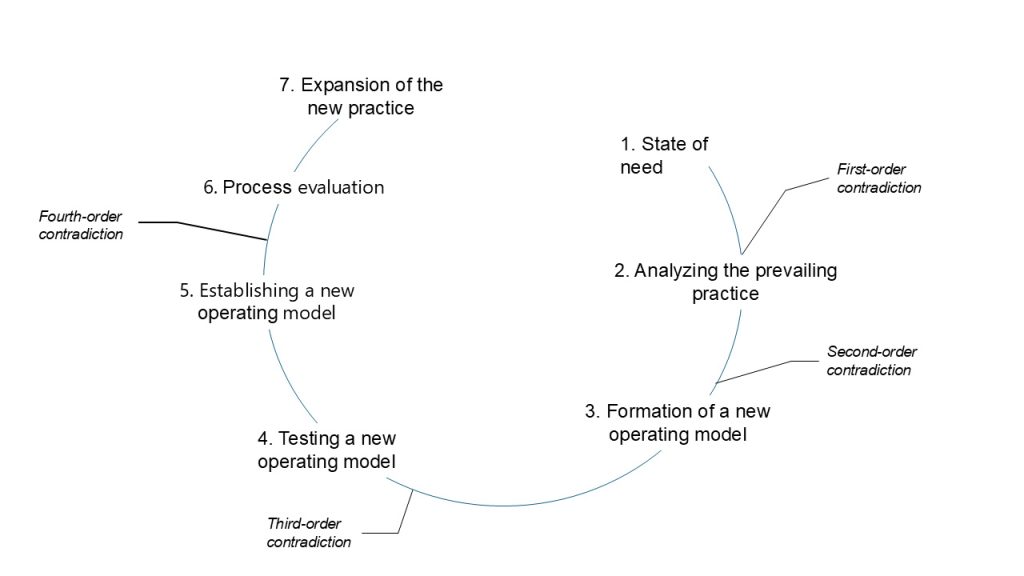

Figure 9. The Circle of Expansive Learning (Engeström, 1995).

4.4 Practice research

In the field of social work, it has been recognised that narrow research is no longer sufficient to address and explain the needs of citizens in increasingly complex and holistic life situations. In addition, in social work – like in medicine, healthcare and rehabilitation, services are expected to involve an evidence-based working practice. However, the field of social work has not felt comfortable with this, because evidence-based service research is seen as oversimplifying complex social issues. However, there is a need for new, task-oriented operating environments for social work research and development, where different experts can work together (Satka et al., 2016).

The need for practice research stems from the practice itself, i.e. service work situations where a problematic issue has been identified. The research has four phases: planning, piloting, implementation, and returning and reflecting on information. In practice research, researchers, professionals, service users, i.e. experts through experience, and novices training in the field often work together with managers, local politicians, citizens and communities. All parties have the opportunity to participate in the formation of research problems. The aim is for the research to provide all parties with a new understanding of the phenomenon under development so that the end result promotes well-being, competence and case management (Satka et al., 2016).

Practical research cannot be defined as a clear-cut research method, but it can be characterised as a culture of knowledge formation that seeks to promote democratic dialogue. Practice research applies methods, tools and concepts that have been proven to be good in social and behavioural science research and development work, while developing new ones. The research is based on contextual perception of knowledge as well as critical and reflective thinking. The concepts, methods and ethics of the research process must follow the principles of science at all stages. As a rule, the researchers involved are experts outside the community being developed (Kääriäinen et al., 2016).

The principles and methods of developmental work research can be used in practice research (Haavisto et al., 2016). In addition, practice research and participatory action research are based on the same pragmatist principles. A key difference between action research and action research is that in practice research, the relationships between actors are not limited to just one development project, but to continuous, often networked cooperation (Satka et al., 2016).

Example of practice research

For example, in a study by Tiina Muukkonen (2016), social workers invited their own client families and partners to participate in the study. Data was collected through research discussion. In the research discussion, the themes are essential for the research, and the aim is to reach an understanding of them through cooperation and joint reflection. Muukkonen emphasises that the research discussions were both practical and research based. In this way, the data collection, practical work and development were carried out simultaneously. The aim of the research discussions was not only to compile the research data, but also to improve cooperation immediately.

5 Stages and methods of development

This chapter describes the stages of the development process and the methods used in them. Methods and tools are an essential part of development activities carried out by work communities. However, their use requires competence and knowledge of which methods and tools are best suited for each work phase. There are major differences in the naming of the methods and tools in the literature.

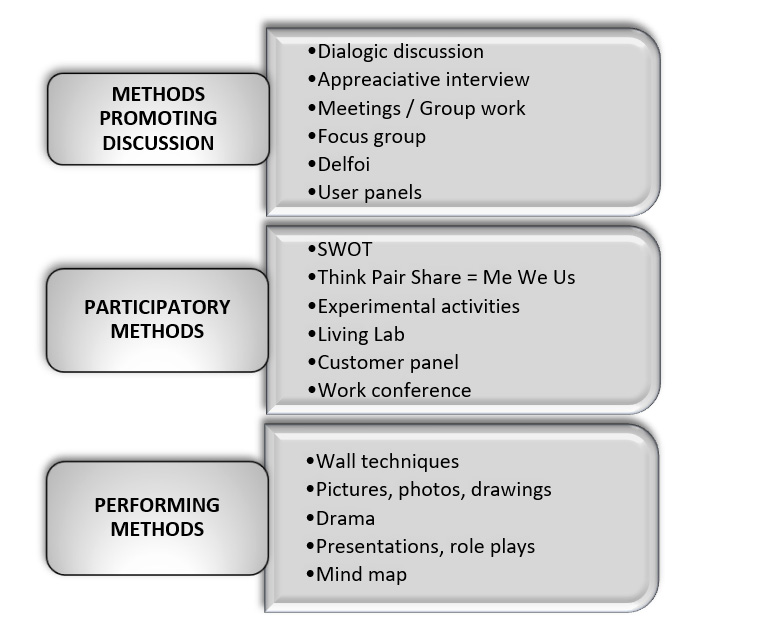

Development methods and tools can be structured in many ways, for example into methods that promote discussion, participatory methods and performing methods. Many methods can serve several purposes at different stages of development.

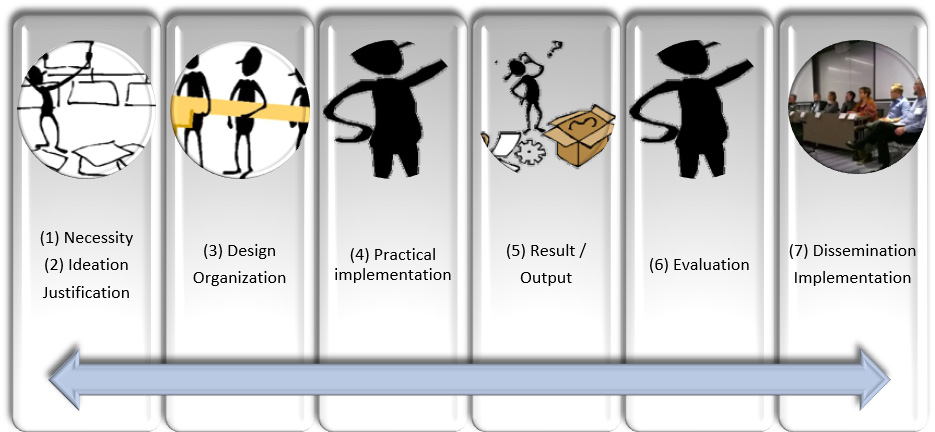

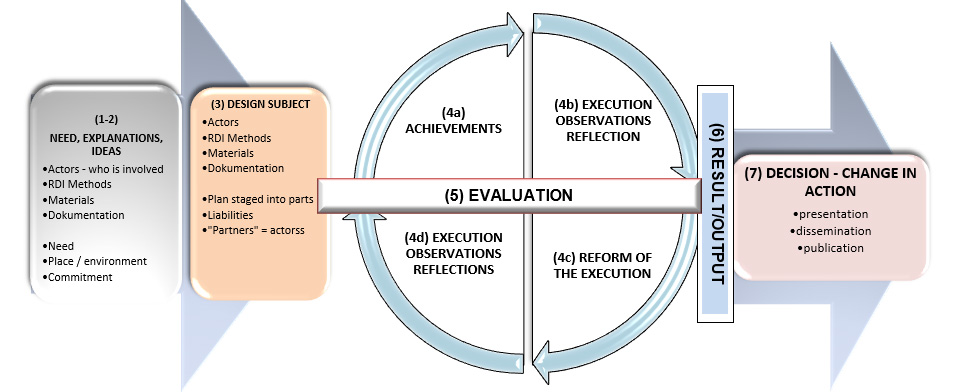

Practical work proceeds as a cyclical process, from identifying the need for development to disseminating results. The work consists of the following phases: (1) identification of development needs for current practice, (2) ideation phase (3) design phase, (4) implementation phase, (5) result and/or output, (6) evaluation phase and (7) decision, implementation and dissemination of results. In practice, the different phases of development are often intertwined.

Image 6. Preparing for a development day in small groups.

5.1 Development phases and constructivist model

Figure 11. Linear progression of development activities.

Figure 12. The cyclicality and reflectivity of development activities as a continuum.

The speed and complexity of changes in the operating environment require development participants to tolerate uncertainty, respect the views expressed by others and flexible decision-making at different stages of operations (e.g. Engeström, 2004; Toikko &; Rantanen, 2009). This way of working can be described according to the constructivist model (Figure 13), in which linearity and cyclicality occur at different stages. In this model, it is essential to recognise the built-in basic idea in all phases: all development is ultimately based on working together, participation, learning in action, continuous reflection and methodological competence. The cohesive forces of development activities are communality, participatory leadership and an evaluative approach to work.

Constructivist work involves strong reflection and consideration of human factors. In practice, this means stopping, evaluating and moving forward, as well as discussing on an equal footing. Development activities progress through interaction towards polyphony, presenting different perspectives and sharing expertise. Figure 13 summarises the basic concepts of the constructive model. However, it is a description of a developmental reality that does not exist as such. The ultimate purpose of the model is to simplify the development process and at the same time give actors the tools to structure their own work.

Figure 13. Constructivist model of development (paraphrased by Salonen, 2013).

5.2 Development methods and tools

Development methods can be structured in many ways. There are also differing views on their relationship to research methods and methods used in project activities. Sometimes research methods serve the development work best: such as a survey or an interview to identify needs or evaluate results. On a general level, the methods are practical means and working methods that help to achieve the objectives of development. However, it varies as to what is actually called a method.

In the literature and practical work, the boundaries between methods and tools are therefore contractual and open to interpretation. Development methods include both narrow-minded development tools and more extensive methods, such as lean thinking, service design, balanced scorecard BSC, working conferences and standardised quality systems. Some methods promote brainstorming, discussion or participation, while others are suitable for describing and presenting development activities (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Examples of methods and tools for development activities. (7)

(7) Many methods and tools can be used in the development phases that are not mentioned in Figure 14. Therefore, for example, it is sensible to look for facilitation tools in the literature according to how they would best promote practical development work. Also note that many of these are also management tools.

5.3 Development phases 1–7

(1) Identifying the development needs of current practice

Identifying the need for development is the driving force behind development activities. For example, a need for change has emerged in practical work, which is why development activities will be implemented. At this stage, it is also important to form a common understanding of the area of development and to define the topic area sufficiently, but not in a fixed manner.