Yhä useampi nuori Suomessa kokee yksinäisyyttä, ulkopuolisuutta ja eristäytyneisyyttä. Tähän ongelmaan pyritään puuttumaan NOPPA-hankkeella, jossa osallisuutta lisätään pelillistämisen avulla. …

Towards Sustainable Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania: SUSIE Project Experiences

Introduction

Dear Reader,

The SUSIE project warmly welcomes you to read this publication, which presents some of the remarkable results of the extensive collaboration. The four-year development project of the universities of the Global South and North has operated within a complex development context. Characteristics of these are that the progression from cause to effect eventually follows a logical order, although logic becomes apparent only later through decision making analysis (see Chapter 1). In addition, the uniqueness of each project makes replication impossible, so it is difficult to find predefined solution models, and all starts from scratch. This publication is a lens through which the reader can view the complex development process and its results in a compact form.

SUSIE, Sustainable Business and Employability through HEIs’ Innovation Pedagogy, was comprised three Tanzanian HEIs — Tumaini University Dar es Salaam College (TUDARCo), now Dar es salaam Tumaini University (DarTU), Moshi Co-operative University (MoCU), and Mwenge Catholic University (MWECAU) — alongside the Finnish Turku University of Applied Sciences (Turku UAS), which served as the project coordinator. The consortium did not arise from the vacuum, but the foundation rests on former development initiatives during which partners had not only established confidential relationships but also invested in capacity building (Chapter 3). This basement enabled SUSIE to set ambitious goals and follow capacity building as defined by the United Nations, UN:

Capacity-building is defined as the process of developing and strengthening the skills, instincts, abilities, processes, and resources necessary for organizations and communities to not only survive but also adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing world. Central to capacity building is a form of transformation that emanates from within, extending beyond mere task performance to encompass shifts in mindsets and attitudes.

The UN recognizes universities as key enablers of capacity building, particularly through research, development, and innovation (RDI) initiatives that empower communities and societies to pursue sustainable development goals (SDGs). While SUSIE remained dedicated to all SDGs, the project identified SDG 4 Quality Education, SDG 5 Gender Equality, SDG 8 Decent Work, and SDG 9 Innovation as its cornerstones (Chapter 1).

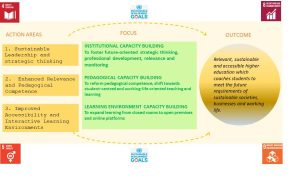

As shown in Figure 1, the project comprised three operational areas, within which, activities related to their content were implemented. In the action area of Sustainable Leadership and Strategic Thinking (Chapter 1 and 2), the focus was on developing institutional capacities with forward-looking approaches and relevance. The second activity area, Enhanced Relevance and Pedagogical Competence (Chapter 3,4 and 5), prioritized pedagogical proficiency by improving teaching competence, emphasizing a student-cantered approach, and integration with working life. Simultaneously, the third result area, Improved Accessible and Interactive Learning Environments (Chapter 4 and 5), concentrated on strengthening the capacity of learning environments. More specifically, this involved expanding learning opportunities beyond traditional classrooms to open spaces and digital platforms. The outcome of SUSIE was achieved through mentioned three action areas, collectively driving transition and ensuring more accessible, relevant, and socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable higher education.

Figure 1. The action areas, focus and outcome of SUSIE.

Acknowledgements

The SUSIE project has been blessed by highly motivated team members and committed institutions, yet without the backing of extensive networks and stakeholders, its efforts had remained modest.

Firstly, the project would like to extend its deepest appreciation to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland and the Finnish National Agency for Education, without whose funding through the Higher Education Institutions Institutional Cooperation Instrument (HEI ICI), the project’s goals for sustainable capacity building would never have materialised. SUSIE acknowledges the efforts of the HEI ICI team, particularly Ms. Kaija Pajala, who has patiently provided extensive assistance to the SUSIE team. The eight projects within the HEI ICI family have been significant peer supporters and encouragers. Specifically, SUSIE wants to express sincere gratitude to the GeoICT4e project for its invaluable support and friendship, upon which SUSIE has relied, regardless of the nature of the issue.

SUSIE is deeply indebted to the institutions behind the partnership. The project is extremely grateful to Turku University of Applied Sciences, Moshi Co-operative University, Mwenge Catholic University, and Tumaini University of Dar es Salaam College, which have supported the project, closely followed its efforts, and provided comprehensive assistance, addressing needs regardless of their scale or nature, abstract or concrete. Beyond this, these institutions have demonstrated profound belief in the project and serious interest in its progress. Your unparalleled support has formed the cornerstones of the project.

The SUSIE board, CEO Paula Fontell, Ethica; Dr Blandina Kilama, President’s Office; Dr Eugene Lyamtane, DVCAF MWECAU; DVC ARPE Prof. Andrew Mollel, DarTU; CEO Jumanne Mtambalike, Sahara Ventures; CEO Aika Robert Nkya Shujaa Tours; Prof. Alfred Said Sife, VC MoCU and Dr Vesa Taatila, Rector-President Turku UAS, has proven to be the real dream team! Board members have not only fulfilled their duties but also consistently advised the project, provided direction during challenging periods, and facilitated networking with various stakeholders. Their unwavering guidance and constructive criticism have been fundamental in achieving goals and going further. In addition, exceptional professionals have stood by SUSIE. Sahara Ventures, thank you so much! You have been exemplary in your tireless support, not only for the project but also for stakeholders and students, demonstrating a holistic, curious, and forward- looking innovative attitude that has been invaluable. SUSIE extends profound gratitude to Dr. Petri Uusikylä whose curious and innovative mindset has offered endlessly new perspectives which have enriched and highly benefited the project’s actions, thinking, and outcomes. SUSIE is also grateful for the high proficiency of Zaidi Recyclers, which has nurtured the project and facilitated the transition from theory to practice. Millions thanks to Ehica for its visionary thinking, which has motivated SUSIE to transcend the conventional. It has been a great honour collaborating with all of you!

Without the colleagues and students of partner institutions, SUSIE would not have succeeded. Dear colleagues, words cannot express our gratitude for your patience and participation. Thank you for dedicating your precious time to various events and trainings organised by the project. The continuous discussions about SUSIE on campus were undoubtedly exhausting, yet you encouraged and motivated SUSIE to continue. To all students, you have been amazing! Your positive attitude and motivation to learn cannot be overstated. You inspired us to continue, and we thank you for showing us that sustainable transformation is indeed achievable!

People are the driving force behind human action. SUSIE extends its heartfelt thanks and deepest gratitude to every individual who participated in project activities, shared their views, and contributed to building capacity that enhances higher education, the working life, and the future of graduates.

Acronyms and abbreviations

COSTECH Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology

COVID Corona Virus Disease

HEI Higher Education Institutions

HESLB Higher Education Students’ Loans Board

ICT Information and Communication Technology

ILO International Labour Organization

IRIS Introducing Reverse Innovation to Higher Education Institutions In Tanzania

KAB Know About Business

MoCU Moshi Cooperative University

MWECAU Mwenge Catholic University

NACTE-VET National Council of Technical Education and Vocational Education in Tanzania

NICHE Netherlands Initiative for Capacity Building in Higher Education

NORAD Norwegian Agency for Development

OUT Open University of Tanzania

SDG Sustainable Development Goals

SUSIE Sustainable Business and Employability through Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania

TIE Tanzania Institute of Education

Turku UAS Turku University of Applied Sciences

TUDARCo Tumaini University Dar es Salaam College

UDIEC University of Dar es Salaam Innovation and Entrepreneurship Centre

UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Organization

Sustainable Leadership and Transformation of Higher Education Institutions

Introduction

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are complex systems tasked with educating individuals and advancing science, knowledge and culture. As societal expectations evolve, there is a growing demand for HEIs to play a more significant role in addressing common issues. Sustainable leadership has emerged as a strategic approach aimed at fostering positive transformation, developing social capital and nurturing an innovative environment for the future.

Tanzania’s population ranks among the world’s fastest growing; it currently stands at 65 million, with approximately 70% aged between 15 and 35. The National System of Innovation has emphasised the increasingly active role HEIs should play in sustainable development. This underscores the importance of institutions investing in holistic strategic thinking, facilitating knowledge exchange beyond organisational boundaries and fostering the development of environmentally and socially responsible practices.

SUSIE, or Sustainable Business and Employability through HEIs’ Innovative Pedagogy, is a capacity-building project which aims to enhance strategic thinking, pedagogical competence and interactive learning spaces within Tanzanian universities. Serving as a crucial component in a series of initiatives focused on community learning and addressing local needs, this project plays a vital role in fostering sustainability.

This chapter focuses on the Sustainable Leadership Training Course, a one-year programme organised by the SUSIE project and offered to Tanzanian university leaders and managers. It delves into the systems change approach underpinning the training, while also introducing the concept of sustainable leadership as pivotal for organisations to contribute to societal resilience. Additionally, the chapter explores sustainable thinking as outlined within the SUSIE project in the context of sustainable leadership.

Systems change approach to developing HEIs in Tanzania

The urgency of many global policy concerns such as climate change, the green transition and social sustainability requires that more focused attention be paid to the connections between knowledge generation, educational strategies and curricula, and higher education policy formulation. In particular, the sustainability agenda compels us to adopt improved practices that anticipate and consider future developments. We interpret this transition as a shift from a conventional linear model of knowledge dissemination to a systems-driven model. The new approach is characterised by a forward-looking, anticipatory and ecosystemic perspective. In this model, support is provided to individuals, institutions and systems based on their overall engagement within the system, rather than focusing on specific stages or nodes in a policy cycle (Hopkins et al., 2021).

Tanzania’s higher education system has developed in a positive direction over the past ten years. In universities, strategic thinking has strengthened and the focus in curriculum design has shifted from traditional lecture-and-exam teaching to a more applied and student-inclusive approach. This has been clearly visible during Finland’s Higher Education Institutions Institutional Cooperation Instrument, HEI ICI, funded SUSIE and IRIS projects. The enhanced cooperation network between universities and their key stakeholders (a key focus of the IRIS project, along with innovative pedagogy) has been particularly noteworthy. The central focus of the SUSIE project has been to include an emphasis on sustainable leadership as part of the strategic development of universities.

Still, the existing institutional frameworks of contemporary research, including the academic publication system, career paths, departmental hierarchies and the standards for assessment and funding, sometimes fail to provide adequate support for innovative methods of generating knowledge. However, there is a growing demand for these new methods to align with the requirements of sustainability and the shift towards environmentally friendly practices in many policy areas. The transition from providing information to putting it into action, and ultimately to re-evaluating and redesigning, has been taking place for a considerable time. The dominant principles now progressively prioritise the transition from being responsible for outcomes to achieving significant effects, and potentially even to anticipating future developments, collaborating in the creation process and collectively making sense of situations.

The emergent approach to the strategic steering of Tanzanian universities is driven by ecosystems, where the provision of and demand for knowledge and the ways it is shared are becoming more complex and forward-looking. This method sets the stage for “anticipatory governance” in a broader context. In examining this change, we concentrate on the trust that exists within the government, evidence and knowledge, citizens, institutions and organisations. At the SUSIE project we aim to establish “systems navigation” as the method through which the shift from relying solely on expert- based scientific advice to a more comprehensive approach that emphasises systems and solutions takes place. This approach involves more collaborative, shared and open sense-making processes, enabling all participants in the governance system to bypass unnecessary hierarchies and sectoral obstacles. As a result, they can arrive at more suitable policy solutions in an increasingly intricate policy landscape.

The long-term development of Tanzania’s higher education system should be seen as a systemic transformation instead of a linear development path, where many social and socio-technical forces of change affect the emergence of new operating models and cultures.

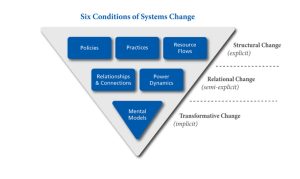

Systemic change can be investigated from the standpoint of the factors and situations that enable change. John Kania, Mark Kramer and Peter Senge (2018) have identified six factors that condition systemic change, which are structured into three levels of change. The structural level of systemic change consists of operational principles, operational practices and resources. The structural level is concretised on the one hand as society’s institutions, management practices and regulatory solutions that enable and limit the interaction of actors. On the other hand, the question concerns the distribution and allocation of material and immaterial resources. At the level of relational change, relationships, interactions and power dynamics influence systems change. The number of relationships and the quality of connections has a decisive role on what kind of influences we are exposed to at any given time. At the level of transformative change, the core factor is the mental models of individuals, i.e., those deeply rooted habits that make us take things for granted and that guide our thinking, what we do and what we say.

Figure 1. Six Conditions of Systems Change (Kania et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Six Conditions of Systems Change (Kania et al., 2018).

According to Gregory Bateson (1972), knowledge in social systems is not transmitted passively. Learning takes place when we assign meanings to signals and convert them into information and knowledge. The latter transformation can be called a “difference that makes a difference” to the recipient of that information. Learning is the process of marking these differences. Therefore, mental models, relationships and structural factors all have a simultaneous effect on systemic change. The challenge of the anticipatory governance approach is to connect these to the basic assumptions of the model and define the way in which the dynamics of change can be understood as part of a complex decision-making process.

In the discussions held during the training programmes and workshops of the SUSIE project, a position was taken on the ability of the three participating universities (Moshi Cooperative University (MoCU), Tumaini University Dar es Salaam College (TUDARCo) and Mwenge Catholic University (MWECAU)) to change, their desire to reform and the possibilities of systemic change. All of the participating universities had a clearly identified desire to reform and develop and to apply the approach of the Sustainable Leadership programme. Regarding the ability to change, the participants were positive: although there were differences in the starting levels (above all, with regard to heterogeneity), the belief in the ability to change was strong.

Regarding relational change, there were clear differences between strengthening networks and changing power structures. While cooperation between the universities has already improved enormously during the SUSIE project, changing power structures was found to be significantly more difficult. The latter concerns the traditional management and operating culture, the path dependency caused by which slows down the implementation of change. Above all, the rigidity of power relations can be seen in the relationships between the universities’ administration/top management and developers. Furthermore, the institutional rigidities of the entire education system in terms of teaching plans, funding and the low delegation of decision-making power may cause slowdowns. The latter belong to the highest, i.e., the structural, level of the model. In this regard, the change programme calls for macro-level structural reforms which will affect the entire Tanzanian higher education system.

Sustainable Leadership

According to Dos Santos and Ahmad (2020), sustainable development is characterised by dynamism and complexity.This implies that organisations aspiring to address sustainable development challenges must be not only capable, competent and high-performing but also have leadership which is committed to promoting sustainable development. In the late 1980s, the Brundtland Commission made a link between sustainable development and leadership, from the perspective of a future where environmental and human needs coexist. This line of thinking has since evolved, with Hargreaves and Fink (2004) associating sustainable leadership with educational institutions and introducing seven principles that denote the characteristics of sustainable leadership as follows:

- Fostering continuous learning

- Pursuing long-term success

- Embracing communicative and inclusive decision-making

- Advocating for social justice

- Respecting human and material resources

- Promoting diversity

- Engaging with the community

The year 2015 marked a significant global milestone in sustainable thinking with the launch of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Agenda 2030. While national commitment to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is significant, integrating various organisations into the agenda was recognised as imperative for concrete actions to be taken (Cesário et al., 2022).

At the organisational level, Liao (2022) underscored the importance of sustainable leadership as an essential concept when it comes to translating SDG thinking into actionable strategies. By fostering strategic competence and promoting an organisational culture that embraces sustainable thinking, leaders can ensure that sustainable approaches are ingrained within their organisation. However, this requires leaders to have strong commitment, a long-term strategic vision and the willingness to invest in shared decision-making and innovation.

Within the framework of sustainable leadership, the value of human resources is key. Additionally, responsible people-management practices prioritise employee well-being and competence development (Avery and Bergsteiner, 2011b). Liao (2022) argues that the sustainable leadership approach seeks resilience through continuous learning, achieving long-term success, promoting social justice and meeting stakeholder needs while maintaining economic, social and environmental balance.

Outlining sustainable thinking

The theory of change and the concept of sustainable leadership within the SUSIE project are discussed above. This section, in turn, concentrates on sustainable thinking which underpins the Sustainable Leadership training. This perspective is grounded in the SDGs, which serve as basic principles for advancing sustainability within higher education. The overall aim is to encourage HEIs to invest in the common goals so that institutions are seen as stable operators which produce culturally, socially, economically and environmentally sustainable competencies and knowledge. Rather than understanding sustainability as the subject matter of a particular course or programme, we propose that sustainability be built into HEIs and function as a guiding principle of institutions. Four SDGs—Quality Education, Gender Equality, Decent Work and Innovation—are extensive and provide an excellent backbone for educational institutions. These may steer universities towards long-term strategic planning, encourage them to foster interaction with society, motivate them to scan the signals from the environment and follow global change drivers. Success with regard to these SDGs requires professional management, with a holistic view of HEIs as essential enablers of positive transformation.

Figure 2 is a simplified model of a university, illustrating the intense interaction between university operators: the domain of Management and Administration is on the left side and the domain of Teaching and Learning is on the right side. In the Management domain, four key sectors are highlighted: Community Well-Being and Professional Development, Future Visions and Strategies, Transparency and Quality Assurance, and Innovativeness and Openness. Similarly, in the Teaching and Learning domain four approaches are outlined: the pedagogical approach, the competence approach, the curriculum approach and the innovation approach. The two domains are intricately linked by strategic guidelines which significantly influence all university operations including teaching and learning. Implicitly, society and working life are included in the image. The transparency and innovativeness of universities encourages working life initiatives and the integration of identified community needs into the learning process.

Figure 2. Sustainable Thinking, SUSIE Project.

The objective of the Teaching and Learning domain is to facilitate sustainable learning, characterised by a forward-looking curriculum that aims to cultivate relevant competencies through active pedagogy methods, innovative approaches and appropriate content. Achieving this requires strong motivation among teaching staff, which management should support by ensuring their well-being and providing opportunities for professional development. Consistency in leadership is not only about following a plan but also about being reliable, predictable and trustworthy. Budget planning and financial oversight are significant factors for HEIs. In terms of risks, funding is acritical factor for universities which requires active exploration of external innovation funding sources. Externally funded Research, Development and Innovation projects provide HEIs with a huge number of opportunities such as new partnerships, updated skills and knowledge, increased relevance and improved capacities.

A HEI is typically a large and diverse community, with members numbering in the thousands when students are included. Effective leadership of an extensive institution necessitates long-term strategic planning capabilities to steer the organisation towards desired futures. The concept of performance-based management highlights quality processes which establish targets and monitor achievements, primarily evaluating how well strategic areas are being executed. The theory of change serves as a roadmap which illustrates how initiatives are expected to yield outcomes and impacts, while also uncovering underlying assumptions regarding the mechanisms of change. According to the prevailing paradigm HEIs are expected to be significant in society in terms of education and in particular research, development and innovation.

Sustainable Leadership programme

Tanzanian university leaders possess a robust academic background and have acquired leadership skills through years of practical experience within institutional settings. However, they may lack formal qualifications due to limited training opportunities.

The Sustainable Leadership Training programme was developed to address some of the recognised challenges faced by HEI leaders in Tanzania. Firstly, the training aimed to establish a common platform for discussion and knowledge sharing. Secondly, experts from Finland and Tanzania introduced emerging leadership trends and drivers of change, equipping participants with new tools and knowledge to enhance and update their leadership competencies. The one-year training programme (2021-2022) comprised 10 online sessions and culminated in the Academia Sparks Forum, which attracted an audience of 135 individuals who were invited to discuss the strategic sustainable transformation of HEIs.

In total, 18 leaders graduated from the programme, all of whom indicated high satisfaction with the arrangements and content of the training in the post-programme evaluation. Participants found the views presented engaging, and feedback on the expertise of the trainers was overwhelmingly positive. Participants expressed that the programme generated numerous new ideas and initiatives which could be implemented in practice.

These topics were very relevant and useful, especially for newly appointed lea- ders like me. This training really equipped me with skills and knowledge I needed and perhaps would not get elsewhere. I learned very seriously, and it helped me very much.

Overall, participant feedback on the Sustainable Leadership programme was positive. Above all, the participants felt that the programme’s holistic, systemic perspective helped them understand the relationships and interdependencies between complex phenomena. At the same time, it was noted that the university’s strategic management model, outlined in the form of a modular structure, meant that it was possible to arise only some areas (e.g., results management or strategic planning) to the university’s development platform.

Conclusion

This chapter has analysed the role and value added by the Sustainable Leadership Training programme. The SUSIE project organised a programme specifically for university leaders and managers in Tanzania. This text explored the systems change method that underpinned the training and introduced the concept of sustainable leadership as a crucial paradigm for organisations to contribute to societal resilience. In addition, the chapter examined the concept of sustainable thinking as defined in the SUSIE project, specifically in relation to sustainable leadership.

The key insight regarding the year-long Sustainable Leadership programme and its implementation requirements is that the programme’s objectives must be comprehended within the context of a larger systemic transformation. For Tanzanian higher education institutions to successfully undergo renewal, it is necessary for change to occur simultaneously at three levels: transformative (mindsets and mental models), relational (networks and power structures) and structural (policy, regulation and context).

The chapter emphasises our positive observation that the three universities involved in the project have already initiated transformation at both the transformative and relational levels. The shifts in the cognitive and operational approaches of individual developers and change agents have also motivated others to join the endeavour. The network-like operating model is being reinforced through peer learning, joint development workshops and the aspiration to be a benchmark for other universities.

The update has not yet extended to the process of renewing the entire system. It is crucial to engage the ministries and innovation agencies responsible for the development of the entire university system in the upcoming phase. Positive experiences at the local and regional levels promote growth at the system-wide level.

References

Avery, G. C., and Bergsteiner, H. (2011b). Sustainable leadership practices for enhancing business resilien- ce and performance. Strategy Leadership, 39, 5–15.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Paladin Granada. London.

Cesário, F. J. S., Sabino, A., Moreira, A., and Azevedo, T. (2022). Green human resources practices and person-organization fit: The moderating role of the personal environmental commitment. Emerg. Sci. J., 6, 938–951.

Hargreaves, A., and Fink, D. (2004). The seven principles of sustainable leadership. Educational Leader- ship, 61, 8–13.

Dos Santos, M. J. P. L., and Ahmad, N. (2020). Sustainability of European agricultural holdings. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, 19, 358–364.

Hopkins, A., Oliver, K., Boaz, A., Guillot-Wright, S. and Cairney, P. (2021) Are research-policy engagement activities informed by policy theory and evidence? 7 challenges to the UK impact agenda. Policy Design and Practice, 4(3), 341-356.

Kania, J., Kramer, M. and Senge, P. (2018). The Water of Systems Change. https://www.fsg.org/publica- tions/water_of_systems_change

Liao, Y. (2022). Sustainable leadership: A literature review and prospects for future research. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 1045570.

Sustainable Leadership in HEIs in Tanzania: Prospects and Challenges

Introduction

Good and sustainable leadership in any organisation is crucial for sustainable development. Leaders inspire passion, motivate followers and ensure support and tools are available for the achievement of goals (Perry, 2022). They have a vision to realise and develop employees through coaching and mentoring (Perry, 2022; Zhai, 2021). Thus, sustainable leadership “has an activist engagement with the forces that affect it, and builds an educational environment of organisational diversity that promotes cross- fertilisation of good ideas and successful practices in communities of shared learning and development” (Cook, 2014).

Moreover, sustainable leadership drives solutions for environmental, social and economic challenges (Perry, 2022). It recognises leadership as influencing processes and breaking down silos to combine efforts for change. Sustainable leaders embrace complexity, becoming adaptable. They view business as interconnected with people and the environment (Wright and Horst, 2013). The university system should educate students to lead responsibly. Driven by strong values, sustainable leaders focus on long- term impact, preparing organisations to flourish and expand.

Sustainable Leadership in HEIs

Higher education institutions (HEIs) in Tanzania are dynamic organisations. Several transformations are currently taking place in these institutions as part of that dynamism, especially in terms of leadership, expansion of campuses and facilities, the programmes offered student admissions, staff recruitment, research agendas and many more areas. Much of the transformation and growth happening in universities requires innovative leadership (Wright and Horst, 2013). Thus, sustainable and strategic leadership is crucial in HEIs. Sustainable leaders in higher education institutions must become change actors, considering the needs of present and future generations and encouraging professionals who are skilled and aware of Sustainable Development (SD). Yue, Feng and Ye (2021) assert that sustainable leaders emphasise innovative and creative abilities in systems.

Taking this into consideration, SUSIE project leaders organised a number of leadership training workshops for HEIs between June 2021 and May 2022, in which a number of critical issues were covered. During this period, eight online training workshops led by facilitators from Finland and Tanzania were conducted. The workshops were attended by Tumaini University Dar es Salaam College (TUDARCo), Mwenge Catholic University (MWECAU) and Moshi Cooperative University (MoCU) SUSIE teams, and focused on sustainable leadership specifically with regard to Strategic Planning, Foresight and Leadership, Result-Based Management, Systems Thinking, Complexity and Leadership, Leadership in Action, and Leadership and Responsible Communication. Similarly the training involved articulation of the goals of the strategic leadership strategy, identification of key stakeholders and their acceptance of the strategy, description of the effect of the strategy, articulation of what will constitute a successful strategy, and defining and embedding elements such as vision, mission and values as well as the timeframe. They also involved issues related to the inputs needed when developing a university strategy.

A university strategy provides a rationale for the existence of the university and its mandate. Its articulation involves gathering views from different stakeholders such as government/ministries and agencies, the university owner(s), the board of directors, the student body, local organisations and local people. Considering the perspectives of multiple stakeholders is vital to ensuring long-term commitment to the development of the university.

A university cannot achieve its strategic thrusts without active internal stakeholders. These stakeholders include staff and students who are central to putting the strategy into action. Coordinating internal stakeholders involves bringing everyone together to discuss how strategic goals can be achieved. Wright and Horst (2013) argue that HEIs leaders need to offer induction programs to help new faculty members comprehend the university system, enhance faculty potential, promote involvement in interdisciplinary research and collaboration with industry, and enable the expansion of opportunities for innovation. Ultimately, sustainable leadership in HEIs will contribute to knowledge creation which is needed for innovation (Iqbal and Piwowar-Sulej, 2021).

Strategic planning involves creating a good story that connects people with the university’s strategy. This may involve stories about excellence in action. The story may enable partners and proponents to be informed about different university strategic initiatives such as innovation, innovative pedagogy and research and development, as well as partnerships.

Furthermore, strategic planning involves making decisions and identifying key stakeholders in order to share the strategy. Taking into account the content of the strategy and the context in which the university operates, these stakeholders may include staff, students, national decision makers, local decision makers, local organisations, partner universities/organisations, financiers, supporters and proponents. Decisions made regarding the existing strategy/ies are important in maintaining continuity, achieving goals and ensuring stakeholders’ trust. Thus, the thrust of the strategy must be followed in order to achieve and maintain its imperatives.

Attributes for Sustainable Leadership

Goolamally and Ahmad (2014) identified the attributes of a sustainable leader: 1. Rightness: the quality or state of being morally good, justified or acceptable; 2. Progressiveness: the ability to implement reform, adopt a strategy and motivate others; 3. Inspiring: having the means to gain support and exercise influence; 4. Competence: specifically action-orientation competency and emotional or spiritual competency; and 5. Self-efficacy: the belief in one’s ability to do something successfully. Other scholars around the world like Fatoki (2021), Gisela (2019), Iqbal (2021) and Liao (2022) have argued that sustainable leadership in HEIs is attributable to institutional vision and mission alignment, ethical decision making, stakeholder engagement, innovation and adaptability, national and international collaboration, and continuous empowerment and development of the members of the institution and other stakeholders.

Leaders in HEIs should strive to attain these attributes for the prosperity and sustainability of their organisations. Leaders from MWECAU, MoCU and TUDARCo had the opportunity to share their profound experience and leadership skills during a series of Sustainable Leadership training workshops. In the training sessions, these attributes were discussed and shared. The lessons learnt and their impact in shaping their instructions was also shared.

The Influence of Sustainable Leadership in Fostering Transformations in HEIs

Sustainable leadership plays a vibrant part in the transformation and growth of HEIs. According to Al-Zawahreh et al. (2019), learning organisations are highly concerned about systematic thinking, extensive collaborative engagement and the core assumptions of business and its objectives. As it is a social process, contextual factors influence organisational learning. The shared vision, systemic thinking and leaders of these institutions influence organisational learning.

Foresight leadership is another factor influencing sustainable leadership in HEIs. Cook (2023) defines foresight leadership as the “practice of identifying current and future trends that may impact a business and responding to those changes with strategic planning”. According to this definition, foresight leaders have the ability to impact the business of their organisation and respond to changes. Foresight leaders always have a vision for future transformations of HEIs. Future thinking leadership, theory of change, and systems thinking and change are essential for foresight leadership in HEIs. The core of foresight leadership is the ability to create and maintain quality, coherent and functional forward thinking which greatly influences transformations in universities. It involves examining future pathways, trajectories and uncertainties and making long term and sustainable decisions.

Higher education institutions function as the basic unit to ensure the implementation of sustainable leadership in their respective organisations (Piwowar-Sulej et al., 2021). A successful organisation embracing sustainable leadership will enhance the performance of its people, meet stakeholders’ needs and lead to a positive impact on employee organisational commitment, employee job satisfaction, employee organisational trust, financial management and organisational resilience (Gisela, 2019; Burawat,2019; Liao, 2022; Piwowar-Sulej et al., 2021).

Liao (2022) opined that in learning organisations such as higher learning institutions, sustainable leadership focuses on extensive and in-depth learning that encompasses innovative pedagogy to allow students to acquire 21st century skills, actively shares knowledge and skills, implements innovative and practice-oriented curricula that address community needs, uses curricula that focus on diverse methods of training and assessment to promote innovative skills acquisition, talent identification and growth, and nurtures collaboration and networking skills among students, faculty members and the community at large.

Sustainable leadership in higher learning institutions promotes a high level of practice in terms of the core functions which are research, teaching and learning, and community services. If practiced properly, it fosters efficient and effective high-quality work (Sezgin Nartgun et al., 2020; Iqbal et al., 2020). Sustainable leadership enhances the institutional reputation and customer satisfaction, and stakeholders value an effective communication strategy (Fatoki, 2021; Liao, 2022).

Rehbock (2020) argues that one of the key factors for sustainable leadership is visionary leaders who are strategic in providing guidance concerning the future endeavours of their organisations; this fosters academic credibility, adaptability, innovation and organisational change management. Universities should lead by example, as Luis (2015) opines, by playing a key role in making society sustainable through their capability to perform research activities, develop innovative teaching and learning methodologies, and engage in consultancy and community service to enable a sustainable future. The abovementioned attributes can only be developed if universities are led by visionary leaders who embrace sustainable leadership at the individual, organisational and stakeholder levels, and among the wider community.

However, despite all these promising features that can be the result of sustainable leadership, HEIs—which are considered to be independent thinkers and researchers with excellent expertise in addressing community challenges—may not be able to fulfil their desires. According to Liao (2022), Luis (2015) and Gisela (2019), HEIs face a number of complex challenges as a result of the lack of visionary leaders,which underscores the value of sustainable leadership in organisations. If leaders do not focus on using innovative and flexible curricula with sound pedagogy, they may produce half-baked graduates with limited skills to fit into the job market and to address community challenges. Other challenges include weak university-industry ties, poor stakeholder involvement, poor quality education, poor institutional resource mobilisation and management, limited expansion in terms of numbers and quality of facilities, qualified staff, and research output, weak community and stakeholder engagement and a gender gap (Rupia, 2017) in various managerial positions from departmental level to the university council or senate.

Addressing Sustainable Leadership Challenges in HEIs

Liao (2022) opines that sustainable leadership is highly diverse and dynamic, and aims to address the complex challenges that face organisations. Leadership commitment is one of the best ways of addressing sustainable leadership challenges. Leaders who focus on the sustainability of the institution should set clear strategies and motivate people, particularly leaders, at all levels to strongly commit to following the organisational strategy.

HEIs need to engage stakeholders in their activities by developing practical strategies and policies to engage them. HEIs need to map and identify potential stakeholders including regulatory bodies such as Tanzania Commission for Universities (TCU), Higher Education Students Loans Board (HESLB), National Council for Technical Education and Vocational Education Training (NACTE-VET), National Examination Council of Tanzania (NECTA), Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH), the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, government and non-government organisations, community-based organisations, private firms like Sahara Venture, Innovate Venture and Zaidi Recyclers, start-ups, students, faculty members and alumni. Any potential stakeholders identified should be involved in various steering committees and task forces, and participate in decision making on issues related to university-industry ties, organisational policy and strategy development. HEIs should form strong bonds with their stakeholders to strengthen their relationship.

Proper resource mobilisation and utilisation can be a solution to the challenges facing HEIs in terms of sustainable leadership. Rupia (2017) and Fatoki (2021) have observed that proper utilisation of physical, financial, human and technological resources leads to employee job satisfaction, organisational sense of belonging and low job turnover. Strategic budgeting, planning and resource allocation, transparency and accountability play a big role in minimising leadership challenges and enhancing the growth of a sustainable institution.

Strong institutional policies and guidelines should be in place to support core functions. According to TCU (2019), in order for a HEI to acquire fully-fledged status, it should have a number of policies and guidelines in place. These policies include a human resource policy and operational procedures, a quality assurance policy, a community engagement and outreach policy, a gender policy framework and a library/ICT policy, among others. These policies are crucial in fostering sustainable leadership in HEIs because they demonstrate the institution’s commitment to its mission, vision and goals.

A good organisational structure with a clear line of authority is essential when it comes to fostering sustainable leadership in HEIs. Leaders should embrace teamwork because every individual in the organisation has a unique character and talent that needs to be nurtured and developed. Organisation members should be involved in various working committees, task forces, leadership evaluation and feedback sessions, seminars and workshops.

Conclusion

This chapter has focused on sustainable leadership within higher education institutions (HEIs) to promote sustainable development. It has revealed a need for sustainable leadership in HEIs in Tanzania as many transformations are currently taking place in the education sector which will ultimately result in changes and growth in universities that will require innovative leadership. Sustainable leaders in higher education institutions (HEIs) must become change actors who guide the transformations happening in universities, considering the needs of present and future generations and encouraging professionals who are competent and skilled. The Chapter further revealed the necessary attributes and discussed the influence of sustainable leadership in HEIs when it comes to attaining the vision and mission of their universities. It is clear that sustainable leadership plays a vibrant part in the transformations and growth of HEIs.

Despite the fact that sustainable leadership, if correctly adopted and practised, offers promising prospects for HEIs such as enhancing their reputation, national and international collaboration, fostering innovative culture and promoting a sense of responsibility in every individual working in the institution, there are challenges that can hinder the proper execution of sustainable leadership. However, these challenges have to be viewed as stepping stones which must be navigated if HEIs are to grow further and address the needs and demands of the community. It is crucial for HEIs to prioritise sustainable leadership and make it part and parcel of their strategies and organisational culture, ensuring it is practised by every individual working in the institution.

References

Al-Zawahreh, A., Khasawneh, S., and Al-Jaradat, M. (2019). Green management practices in higher education: The status of sustainable leadership. Tertiary Education and Management, 25(1), 53–63.

Burawat, P. (2019). The relationships among transformational leadership, sustainable leadership, lean manufacturing and sustainability performance in Thai SMEs manufacturing industry. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag., 36, 1014–1036. doi: 10.1108/ IJQRM-09-2017-0178

Cook, S. (2023). Foresight Leadership: What it is and four key characteristics. Retrieved on 12th March 2023 from https://www.mentorcliq.com/blog/foresight-leadership- development

Cook, J. W. (2014). Sustainable school leadership: the teachers’ perspective. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation,9(1).

Dalati, S., Raudeliûnienë, J., and Davidavièienë, V. (2017). Sustainable leadership, organizational trust on job satisfaction: Empirical evidence from higher education institutions in Syria. Bus. Manag. Econ. Eng.,15, 14–27. doi: 10.3846/bme.2017.360

Fatoki, O. (2021). Sustainable leadership and sustainable performance of hospitality firms in South Africa. Entrep. And Sustain. Issues, 8, 610–621. doi: 10.9770/ jesi.2021.8.4(37)

Gisela, C.B. (2019). University and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: processes and prospects. UTERevista de Ciències de l’Educació,1. http://revistes. publicacionsurv.cat/index.php/ute, doi: https://doi.org/10.17345/ute.2019.1

Goolamally, N. and Ahmad, J. (2014). Attributes of School Leaders towards Achieving Sustainable Leadership: A Factor Analysis. Journal of Education and Learning, 3(1). doi: 10.5539/jel.v3n1p122

Iqbal, Q., and Piwowar-Sulej, K. (2021). Sustainable leadership in higher education institutions: social innovation as a mechanism. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education,23(8), 1-20. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-04-2021-0162

Iqbal, Q., Ahmad, N. H., Nasim, A., and Khan, S. A. R. (2020). A moderated mediation analysis of psychological empowerment: Sustainable leadership and sustainable performance. J. Clean. Prod., 262, 121429. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020. 121429

Liao, Y. (2022) Sustainable leadership: A literature review and prospects for future research. Front. Psychol., 13, 1045570. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1045570

Amaral, L.P., Martins, N. and Gouveia, J.B. (2015). Quest for a sustainable university: a review. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 16(2), 155-172 Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2013-0017

Moreira, A., Sousa, M. J., and Cesário, F. (2022). Competencies development: The role of organizational commitment and the perception of employability. Soc. Sci., 11, 125. doi: 10.3390/socsci11030125

Perry, E. (2022). What is a leader, what do they do, and how do you become one? Accessed on 11th March 2024 from https://www.betterup.com/blog/what-is-a-leader-and-how- do-you-become-one

Piwowar-Sulej, K., Krzywonos, M., and Kwil, I. (2021). Environmental entrepreneurship- bibliometric and content analysis of the subject literature based on H-Core. J. Clean. Prod., 295, 126277. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126277

Rehbock, S. K. (2020). Academic leadership: Challenges and opportunities for leaders and leadership development in higher education. In M. Antoniadou and M. Crowder (Eds.), Modern day challenges in academia: Time for a change. London, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rupia, C. (2017). Challenges and prospects in Tanzania Higher Education. Makerere Journal of Higher Education,9 (2), 51-58. Retrieved on 21st March 2024 from https://ajol. info/majohe

SezginNartgun, S., Limon, I., and Dilekci, U. (2020). The relationship between sustainable leadership and perceived school effectiveness: The mediating role of work effort. Bartın Univ. J. Fac. Educ., 9, 141–154. doi: 10.14686/BUEFAD.653014

Salazar-Rebaza., C., Zegarra-Alva, M. and Cordova-Buiza, F. (2022). Management and leadership in university education: Approaches and perspectives. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 20(3), 130-141. doi: 10.21511/ppm.20(3).2022.11

Wright, T. and Horst, N. (2013). Exploring the ambiguity: what faculty leaders really think of sustainability in higher education, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 14(2), 209-227.

Yue, X., Feng, Y., and Ye, Y. (2021). A Model of Sustainable Leadership for Leaders in Double First-Class Universities in China. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(3), 187–201.

Zhai, X. (2021). Combining efficiency and innovation to enhance performance: Evidence from firms in emerging economies. Journal of Management & Organization, 27(2), 295– 311.

Scaling up the Pedagogy Model

Introduction

Background of the FinTan Pedagogy Model

IRIS is an acronym for Introducing Reverse Innovation to Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania. This was the name for a project jointly undertaken by Tumaini University Dar es Salaam College (TUDARCo) of Tanzania and Turku University of Applied Sciences (Turku UAS) of Finland from 2017 to 2020. The project concentrated on a teaching and learning approach that blends together theoretical knowledge and practical skills with a view to addressing an urgent challenge facing higher learning institutions in Tanzania of producing unskilled graduates or graduates with skills that do not match labour market demands. In order to effectively address the gap, the project covered three key areas: development of a pedagogy model that embraces the active teaching and learning approach and which considers local needs, multidisciplinary interaction and knowledge creation. It also aimed to enhance the interactive relationship between the university, entrepreneurs and local communities and focused on improving library and information services to support access to information. Its implementation included capacity building to strengthen active pedagogical skills and enable multidisciplinary cooperation and community engagement. Capacity building training sessions were conducted in Finland and Tanzania and involved issues related to innovation pedagogy, active teaching and learning methods and integration of working life skills into learning processes. Later, the pedagogical methods were tested to see how they fit into the context. It is worth noting that; the intention was not to transfer the pedagogy model from Finland to Tanzania, but to develop a pedagogy model relevant to the local context.

The findings from the tested methods of active teaching and learning and community engagement resulted in the development of a contextualised teaching and learning model which was named the FinTan Innovation Pedagogy Model.

Figure 1. FinTan Innovation Pedagogy Model (Ntulo and Rajala, 2020)

FinTan Innovation Pedagogy Model is a mixture of teaching and learning approaches from Finnish and Tanzania. However, it is generally based on active interaction between instructors, students and the community (i.e. public sector, Non-governmental sector and private sector) during the learning process.

Although the active teaching and learning approach is common, this model is unique in the sense that it places particular emphasis on working life experiences acquired by students through practical working life assignments. This interpretation of active teaching and learning is supported by Freeman et al. (2014), who define active learning as “engaging students in activities that promote analysis, synthesis and evaluation of class content, rather than solely delivering information through lectures”. Basically, linking students with working life is the backbone of the FinTan Model. This learning approach delivered positive results during the IRIS project and has done the same in other parts of the world where it is practiced. For example, in North Carolina the approach has been acknowledged to have a positive impact on students’ learning to the extent that laws have been enacted to compel institutions to establish business advisory councils for the purpose of advising them on the most appropriate and advantageous way of implementing the model (Harper, 2018).

Scaling Up of the FinTan Model

IRIS set a foundation upon which SUSIE project scaled up upon. The scaling up of the FinTan pedagogy model to partner institutions of SUSIE project (TUDARCo, MoCU and MWECAU) had the same objectives as it was in IRIS project of strengthening learning outcomes of university students by improving the theoretical learning and connecting theoretical knowledge with practical knowledge through real life project activities. However, SUSIE extended the FinTan pedagogy model from conventional mode to on online settings for the purpose of building capacity of human resource that can meet current needs of the society, working life and employability. It is imperative to note that, although online learning is not new concept in universities, it gained emphasis during and after COVID pandemic (Dos Santos, 2022). In fact, the COVID challenges caught universities in many developing countries unaware because they lacked required infrastructure and human resources to carry out online learning. Nevertheless, online learning continued to be part and parcel of normal teaching and learning in universities in the world. The human capacity gap that exists in online learning areas was the gap that SUSIE intended to address among other things.

However, knowledge of application of the FinTan pedagogy model in conventional settings was regarded as the basis for application in an online setting. For that matter, before jumping to active online learning, the conventional FinTan model was introduced in partner institutions through training workshops held in each university to build up the foundation of active teaching and learning skills and to promote industrial ties to lecturers who predominantly uses lecture as their teaching method.

The conventional FinTan training concentrated on the application of various active teaching and learning methods in physical classrooms and how to link between classroom lessons with real life experience in the industry. The idea behind this approach is that learners must actively engage in learning in order to perfectly understand the theoretical parts of the lesson before engaging the community in the learning process. This type of learning is based on constructivist theories of learning which emphasises the learner’s use of prior knowledge to connect to new knowledge; by doing so, the learning enhances higher order thinking skills through production and articulation of knowledge. Thus, active learning assignments and projects have to be designed in a way that harnesses the current understanding of learners, makes it explicit and allows integration of prior knowledge into current understanding. This helps students move from the level of memorisation to understanding, improving retention and recall and subsequently promotes creativity, innovation, critical thinking and problem solving skills.

Guided by the thinking outlined above, various active teaching and learning approaches ranging from individual to collaborative, inside to outside the classroom and technology to non-technology-based techniques were shared, discussed and tried out during training. The target was to share and exchange experiences on various techniques and their applicability in Tanzanian university contexts. For example, lecturers who use active teaching techniques in large classes shared their experiences.

Alongside active teaching and learning techniques, linking academia with industry was also greatly emphasised in the training. Discussions on how classroom learning should be linked with industry captivated most of the participants because this is not a common practice in the learning environments of most Tanzanian universities. However, the phenomenon can seem complex to novice implementers as it requires integration of the two different working environments in which the two realms operate. But evidence on its growth worldwide is encouraging. For example, findings on the global trend of linking academia and industry show the collaboration is on the rise (Elsevier, 2021).

In SUSIE as opposed to IRIS, the FinTan model was piloted in the three partner institutions. The pilot phase involved instructors applying active teaching and learning methods in real classrooms and encouraging community engagements in the learning process. The classroom and the community were connected through student’s assignments and projects. Most of the assignment and projects were strategically designed to link classroom knowledge with practical applications in real life. Through the projects, students in collaboration with the respective communities, identified and addressed specific community needs and challenges. By doing so, students acquired knowledge and skills in their subject areas and te community found solutions to the challenges they were encountering.

Each partner university selected courses to pilot the FinTan approaches. The courses, topics and subsequent assignments and projects were carefully selected to ensure that they were not only academically relevant but also tailored to address specific community needs. Student’s execution of the projects involved a range of activities such as carrying out needs assessment, collecting and analysing data to determine the community need and co-creating applicable solutions. The statistics summarized in Table 1 below provide an overview of the students and community members engaged in students’ projects.

Table 1: Statistics on Student-Community Interaction in the SUSIE project.

| S/N | Name of university |

No. of students Involved |

No. of community mem- bers reached | ||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| 1 | TUDARCo | 128 | 143 | 58 | 53 |

| 2 | MWECAU | 19 | 16 | 22 | 18 |

| 3 | MoCU | 72 | 51 | 46 | 62 |

For example, at TUDARCo, a community of upcoming young musician became involved in student’s learning. on Intellectual Property Rights course, students studying for a Bachelor of Laws interacted with upcoming young musicians and discovered that they were victims of the loss of their intellectual property rights in a variety of ways. They co-created a solution that involved training on intellectual property rights in the music industry and the protection of such rights.

Figure 2. A young and upcoming musician singing a song during intellectual property rights protection training for upcoming musicians at TUDARCo (SUSIE project).

At MWECAU students studying for a Bachelor of Education engaged in similar university- industry collaboration whereby secondary school teachers around Moshi town were engaged in student’s learning process. As part of a classroom project, student conducted a needs assessment which led to a discovery that secondary school teacher’s needed capacity building on test construction, procedures and assessment techniques and they collaboratively devised a solution. In addition, business students at MWECAU worked with the business community and identified a need to increase turnover during low tourist seasons as turnover tends to be low in that season. As a solution, a project to improve the digital marketing skills of small entrepreneurs around Moshi town to enable them to sell online was implemented by students.

Figure 3. Moshi town teachers engage in hands-on activities during capacity building training (SUSIE project, 2022).

Similarly, MoCU students also carried out assignments and projects that linked them with the community.For example,students studying Community Economic Development linked with micro-entrepreneurs around the university as part of the classroom assignments. During their interactions, they noticed that the entrepreneurs lacked business planning skills. The students in collaboration with the respective entrepreneurs organised for a training workshop where micro-entrepreneurs were trained on how to develop business plans as well as monitor and evaluate the development of their business. Furthermore, marketing and entrepreneurship students were involved in supporting entrepreneurs in the branding and promotion of their products online.

Feelings and Experiences

Both lecturers and the students who participated in the project acknowledged that this kind of learning is extremely important as it allows students to acquire multiple skills which they would otherwise not have been able to acquire through normal classroom sessions. They also built familiarity with working life. Referring to this type of learning, Tumuti et al (2013) commented in reference to a partnership between Kenyatta University and Equity Bank;

”The students’ benefits from the program are twofold. First, the students are expected to benefit through the training seminars on contemporary issues they are likely to encounter in the communities as they give their service. The seminars and through their real interaction with the communities they serve which makes what they learn during the training seminar a reality. The served communities are expected to gain knowledge and skills from their interaction with the University who are eager to serve the communities they come from. The interaction between the students and their communities help to reduce the gap that exist between them and further familiasize students with the real life in the community where they will live and work after they complete their studies.”

Students who took part in the pilot course and had the opportunity to interact with the community described their experiences of working with people from industry as extra- ordinary. A student from TUDARCo who participated in a project with young upcoming musicians on intellectual property rights, commented that;

Interacting with the community when you are still a student is an eye opener to the opportunities and challenges ahead of you when you are done with your studies. So, it is really important for students to get this kind of opportunity for the purpose of getting themselves ready for working life.

Lecturers also commended the FinTan teaching and learning approaches.They specifically acknowledged their effectiveness in engaging the industry in students learning processes. In a similar context, Ahmed et al (2022) emphasise that students learn most of their skills in the field. Skills such as communication, leadership skills, ethics and professionalism, quality assurance, technical writing and project management are more easily learnt through practice in industry than theoretically in class. Therefore, student’s exposure to the industry needs to be viewed as equally important as attendance in class.

Members of the community who interacted with students also described their feelings. During interaction when a community of street food venders were invited for a training workshop at the university campus, one of the vendors said;

I never in my life imagined that I would one day enter the university compound. So, to me this is a great thing. I have also learnt a lot of things that will help me as I do my work.

The sentiment above sums up the mutual benefits of university-community ties from individual to institutional level. It is indeed obvious that industry accrues enormous benefits from collaboration with universities. One notable benefit is the development of new ideas and innovation. According to Tian et al (2022), enhancing innovation is one of the main reasons that push industry to collaborate with universities as it is a major contributing factor to economic development at all levels of the economy.

Conclusion

In this context, universities and industry depend on each other and therefore must strive to maintain their mutually beneficial relationship. However, universities must take the lead in promoting collaboration especially when the curricula are designed in a manner that allows integration of industry into students learning. The IRIS project and subsequently SUSIE project were basically aligned to this purpose, but with slight different perspectives. In general, the first project paved the way for the latter in terms of active teaching and learning and industrial engagement with the learning process in both conventional and online settings.

References

Ahmed, F., Fattani, M.T., Ali, S. R. and Enam, N. R. (2022). Strengthening the Bridge Between Academic and the Industry Through the Academia –Industry Collaboration Plan Design Model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 875940. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875940.

Dos Santos, L. M. (2022). Online learning after COVID pandemic: Learners’ motivations. Frontiers in Educa- tion, 7, 20th September 2022. Accessed on 23rd Nov 2023 at https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.879091.

Harper, A. (2018). Schools needs industry input to help students connect learning to the real life. K-12 Dive Newsletter. Accessed on 21st Nov 2023 at https://www.k12dive.com/news.

Tian, M., Su, Y. and Yang, Z. (2022). University-Industrial collaboration and firm innovation: an: empirical study of the biopharmaceutical industry. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 47, 1488-1505. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10961-021-09877-y.

Tumuti, D.W., Wanderi, P.M. and Lang’at, T. (2013). Benefits of University-Industrial Partnerships: The case of Kenyatta University and Equity Bank. International Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 4(7).

Active Methods in Online and Blended Learning

Introduction

Presently, the world is marked by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. It is therefore imperative for individuals and institutions to develop capacities that can counteract the situation and eventually turn challenges into opportunities. Across all sectors and industries, there is a growing need for creativity, resilience and innovative problem-solving skills, coupled with the ability to manage rapid changes, make high-risk decisions, and quickly respond to problems (OECD, 2016). In order for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to be able to respond to these needs, the teaching and learning focus should not only be on guiding students to acquire specific technical knowledge and subject-related skills, but also on helping them develop skills relevant for working life, fostering innovation and improving their employability.

This chapter focuses on active teaching and learning approaches in online settings as a response to the uncertainty and disruption of conventional learning that was experienced during and after COVID 19. However, it is also a response to the demand for relevant skills, innovation and employability of graduates who have studied in online environments. According to UNESCO (2020b) online teaching and learning grew exponentially during the COVID 19 pandemic. However, a lot of scepticism also emerged with regard to the quality of the courses in terms of relevant knowledge and skills acquisition and retention. This was the gap that SUSIE project was addressing. For that reason, the emphasis of in the online courses of the SUSIE project was therefore on integration of active teaching and learning components into the online courses with a view to improving the acquisition of skills by learners thereby enhancing employability.

The Justification for SUSIE Online Courses

Currently, the higher education landscape in Tanzania is undergoing transformation in many areas including the introduction of online learning in higher learning institutions (Mtebe and Raphael, 2017). Previously, the mode of teaching in most of the universities and colleges was only in physical classrooms and involved face-to-face interactions between lecturers and students. This traditional mode of teaching has been very challenging due to factors such as the increasing number of students who are currently enrolled in higher learning institutions in Tanzania among others. A major concern has been the outcry from of the industry that most of the graduates entering the labour market are unskilled. On top of that, the COVID-19 outbreak in 2019 also disrupted the conventional teaching and learning in Tanzania just as it did in in many other countries around world. It is indisputable fact that many schools, colleges, and universities in different parts of the world were severely affected by COVID-19. According to the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), over 800 million learners from around the world were affected by this pandemic. One in five learners could not attend school while one in four could not attend higher education and over 102 countries ordered nationwide school closures (UNESCO, 2020b). Due to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, many colleges and universities introduced online courses to run parallel to replace the traditional mode courses. This has democratised the education system and provided different opportunities (Anane and Adusei, 2024). Resilience to such turbulences is an essential mandatory requirement to in higher education institutions in Tanzania and other parts of the world alike. However, ensuring the quality of the service in order to meet the demand of the students in online learning is of paramount importance.

It was in this context that, SUSIE envisioned the need to integrate active teaching and learning into the online environment. Indeed, it is about recognising and accepting the fact that students must be actively engaged in their learning and be exposed to working life even if they are studying in an online environment.This will promote equality of online learning by enhancing the learning outcomes and thereby increasing the motivation of the students. For example, active engagement of by online learners will help them to be curious, mindful, and reflective and have the courage to involve themselves and their thinking into discussions with others just like in face-to-face situation.

Thus, as educators, it is critical for HEIs to rethink, how to equip students with the necessary skills and knowledge needed for personal and professional success through online programmes. An environment must be created that allows online learning to be proactive and aggressive in addressing the dynamic environment of the 21st century. In this regard, e-learning should place learners at the centre of the learning process and recognise that today’s youth, as future adults, have the right to acquire the diverse range of skills and competencies referred to as 21st century skills.

Generally, online learning is justified by the many other advantages it offers. One of the primary advantages is the accessibility and the construction of learning (Pinto & Leite, 2020). Learners from different diverse backgrounds and geographic and socio-economic statuses can access high-quality education without any geographical constraints. For example, students with disabilities, rural students and students with parental responsibilities can still have access to quality higher education (Renes, 2015).

Furthermore, online learning involves a high level of flexibility with learning materials and lectures are accessible at the convenience of students themselves. This enables them to balance their educational activities, employment and other family issues. Similarly, in online environments there is a possibility for the diverse course offerings. Online platforms can host a plethora of courses covering a broad spectrum of subjects. This promotes the growth of the different disciplines which can imparts different vocational training and enhance personal development.

Moreover, online courses are cost-effectiveness. They are cheaper compared to the traditional mode of teaching. The traditional mode of teaching which is also referred to as brick-and-mortar education, sometimes requires students to incur the costs of commuting, accommodation as well as other expenses associated with attending as physical campus. The other advantage of an online platform is that it promotes the use of interactive learning tools such as interactive quizzes, forums, and virtual labs to enhance the learning experience.

Facilitation of Active Teaching and Learning in an online Settings

Effective facilitation of the online courses and especially when using active teaching and learning methods requires adequate knowledge and skills. The SUSIE used a cascade strategy to train teaching staff. According to Boylan and Bett (2016), the cascade training strategy is a way of training many people in a large organisation. A few facilitators from partner institutions in Tanzania (i.e. TUDARCo, MWECAU and MoCU) were trained on how to facilitate active teaching and learning in online classes as trainers with a view that to the knowledge trickling up to as many facilitators as possible. Certainly, from 19 participants the knowledge on active teaching and learning in online environments has cascaded from the 19 participants to many academic staff in all partner institutions in Tanzania.

Figure 1. Training on active online teaching and learning methods for SUSIE partner institutions in Tanzania (SUSIE project, 2022).

Nearly all participants were novice users of the online platforms with limited experience as facilitators. This speaks to the relevance the training but also highlights the challenges involved in what it had to take to introducing participants to a completely new environment they had never been. However, active engagement throughout the training yielded positive results. Specifically, the training covered preparation of on-line course syllabi, designing and development of materials for on-line courses, the use of various on-line learning tools to actively engage and motivate students to learn and evaluation of students learning in on-line settings. These topics addressed from a theoretically and practical standpoint. The theoretical part laid the foundation for practical or hands-on learning. Nevertheless, it was the hands-on activities which were most exciting. These practical exercises provided participants with the chance to apply their theoretical comprehension. Both individual and team learning was used. During the teamwork, participants had an opportunity to share their understanding, ask, argue or challenge each other and thereby reinforce the knowledge while individually participants were tested if they could perfectly do independently what they did together in teams and to view them as more effective as learners were fast, with members prompting each other to practice various skills. Although individual hands-on activities were slower, but learners appeared to be more focused and deeply concentrated on the activities.

Figure 2. Introduction to active online teaching and learning through the Moodle LMS (SUSIE project, 2022).