This is the story of how my life and studies brought me together with a rising startup company named Hydrohex…

Tekijät | Authors

What does it take to succeed in the start-up arena? Start-up survival in the time of COVID-19

Europe, and the world, is currently experiencing a major health crisis due to the COVID-19 coronavirus. Restrictions in terms of mobility and home confinement are being enforced in an increasing number of countries. The economic effects of this crisis are still to be seen but it is already evident that they are going to be significant throughout the world. In this context, start-ups and small and medium enterprises are likely to suffer the most.

It has been known already for decades that new firms have substantially more chances to die than old and established organizations. The term liability of newness, democratized by Freeman et al. (1983), came to summarize this reality and extended Stinchcombe’s (1965) statements of new ventures having a greater risk of failure than other organizations. In Stinchcombe’s words, this risk is due to the dependability on the cooperation of strangers, low levels of legitimacy, and the lack of ability to effectively compete with larger organizations.

It has been known already for decades that new firms have substantially more chances to die than old and established organizations

A different way to look at the same situation is from the liability of smallness prism. These new start-ups are oftentimes regarded as more innovative than incumbents, but they suffer because of their size in addition to their newness. The lack of resources (human, network but mostly capital) poses incredible challenges on the shoulders of these firms. Cash flow, and being able to secure funding rounds, are critical for the survival of these new ventures.

In the context of the coronavirus, analyzing what makes a start-up likely to survive is more urgent than ever. These start-ups will always be affected by the external environment, and black swans, unpredictable events beyond what is normally expected and with potentially severe consequences (Taleb, 2007), are always a possibility, as we now see with the coronavirus. In our VUCA environment (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) making everything possible to ensure the start-ups know their weaknesses and strengths is the only way to minimize adverse environmental conditions.

What success means and success factors in the context of start-ups

As one can already see from the title of this article, the terms success and survival are somehow used indifferently in this article. In order to be able to explain why this is the case, a short discussion on the topic of defining start-up success is needed.

Start-up success is a multidimensional construct and is a term for which multiple definitions exist. Moreover, the definition is highly subjective, and dependent on the definer. For instance, for early-stage start-ups, success is oftentimes equalled to survival, whereas success for more mature start-ups has a lot to do with their exit strategy, their capacity to close M&As (Mergers and acquisitions) or an IPO (initial public offering). At the same time, if we would ask a VC (Venture capital), start-up success is likely to be linked to the start-up capacity to grow its value in a short period of time, while a public investor would probably point to its capacity to generate impact (job creation, impact on economy and the like).

In start-ups with more than one co-founder, a critical aspect to avoid potential issues is to ensure that motivation and vision are shared

These differences can also be found within the start-up itself. In start-ups with more than one co-founder, a critical aspect to avoid potential issues is to ensure that motivation and vision are shared. As a practical example, if success for co-founder A means to create a company that will become a family business, whereas co-founder B sees success as growing fast to sell out, problems are likely to arise.

Start-up success/survival factors

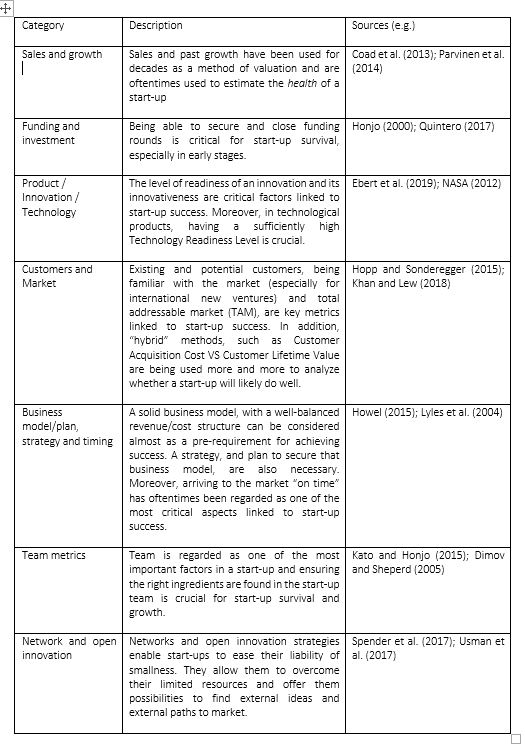

Regardless of the existing discrepancies on how to define start-up success, there is a certain consensus on factors that have an influence on whether a start-up is/will do well. A non-comprehensive summary of different categories of factors can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. A non-comprehensive categorization of start-up success/survival factors

As we see from Table 1 above, there are a number of factors that influence whether a start-up will likely be able to survive/succeed in the start-up arena. A detailed review of some of these factors now follows.

Sales and growth

Sales, and growth that can be attributed to sales, was for long regarded as one of the only ways to assess start-up potential and is oftentimes the preferred way to finance start-ups for both entrepreneurs and investors. These metrics are the most commonly used proxies to forecast whether a start-up will likely survive because they are regarded as fairly objective, and oftentimes are. In other words, numbers don’t lie.

Funding and investment

It goes without saying that new firms without sufficient capital and funding have a higher risk of business failure (e.g. Honjo, 2000). Hence, past track record of securing and closing investment rounds is an excellent proxy to estimate the potential of start-up survival. Once again, one of the most common reasons for (early) start-up failure is unavailability of cash, and funding rounds provide the capital needed when organizations are yet to be profitable.

In this context, the capacity to close funding rounds is strongly related to the ability to convince investors (mostly VCs). Therefore, evolution on valuation (or/and future estimated fair value) and the capacity to grow exponentially, are factors to be taken into account when analysing whether a start-up will likely succeed.

Product / Innovation / Technology

Technology Readiness Level (TRL) is a metric that has been extensively used to measure the readiness of technological innovations since it was developed by NASA back in 1970s. This metric divides the readiness of a technology in 9 levels of increasing maturity (more at https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/heo/scan/engineering/technology/txt_accordion1.html). As its use became more mainstream, organizations started to develop their own metrics to completement TRL. As an example, InnoEnergy, back in 2013, developed its Innovation Readiness Level® by combining TRL with own developed metrics to measure market, intellectual property, society and consumer readiness levels. Similarly, KTH university developed its own Innovation Readiness Level tool with factors such as customer, team, business, IPR, funding, together with TRL (more at https://kthinnovationreadinesslevel.com/).

In addition to such metrics, innovativeness of a product/service, is a factor linked with start-up success. Although it is a common belief that start-ups should be innovative, we also see drawbacks of being innovative and some research points out that introducing market novelties is not necessarily beneficial for newly founded firms and might even endanger their survival (Ebert et al., 2019).

Customers and Market

Other classic factors critical for start-up success and survival are the ones related to track record on customers and market potential. Traditionally, the number of customers and how the customer base is evolving have helped to get an idea on when/if the start-up is likely to break even. Related metrics, such as Total Addressable Market (TAM), has also helped to forecast whether this breakeven is likely to be achieved. In addition to these metrics, access to market and competition affect the possibility to reach out and acquire those customers and are of critical importance.

Lately, other, more elaborated metrics, such as the combination of Customer Acquisition Cost, as the amount of capital it takes to close one customer on average, and Customer Lifetime Value, as the estimation of how much money a customer is expected to spend in the business during her lifetime, have taken the investment world by storm. Leveraging these two metrics ensures that marketing costs, for instance, make sense overall and that money invested in capturing customers will be then brought back, plus a margin, through the customers’ lifetime.

Business model/plan, strategy and timing

A start-up needs a working business model to be able to ensure their generated revenue outnumbers the costs. Having an attractive and sufficient target market is a first requirement but being able to create and capture value are critical. Besides business model as such, strategic orientation is a good predictor for survival (Lyles et al. 2004), and alignment between this strategy and the start-up’s activities is crucial. Moreover, timing, or being able to roll out products or services on-time to get traction, is among the most critical aspects influencing start-up success.

As we already saw, funding is of critical importance for start-ups and, hence, factors that increase the possibilities of getting funded, are extremely important. For instance, business model scalability, as the capacity of a business to grow and expand quickly, allows start-ups to grow faster and exponentially. Investors, and VCs specifically, often look for such models as it (potentially) allows them to harvest returns in the limited time they remain shareholders in the start-ups.

Lately, we have started to see start-ups and investors acutely looking for automatic tools able to assess these aspects, and the number of services aiming, or trying, to do so is increasing. As an example, Pimento (http://www.pimentomap.com/) promises automatic assessment of strengths and weaknesses of business plans. In their own words: pimento is “an easy accurate way to evaluate the chances of success of your business model. It gives the opportunity to entrepreneurs, business angels or venture capital firms to build an objective opinion on a new business idea. It also points out in detail where the model can be improved”. Similarly, Helastica (https://helastica.com/) works as a unified KPI dashboard that automatizes data from sources as diverse as bank statements, Google analytics and team, to help start-ups make informed decisions. At the same time, Helastica has the aim to become “the “Bloomberg” for startups” and help “investors that want to invest in startups but don’t have time to carry out complex due diligences and cannot attend startup related events to discover the next unicorn”.

Team metrics

The start-up team is regarded by investors as a crucial, if not the most crucial, aspect related to start-up success. This is especially the case when it comes to early-stage start-ups searching for their first pre-seed or seed investment in which early investors are likely to bet on the entrepreneur and team rather than the company itself (knowing it will most likely pivot).

Acknowledging the importance of the team, a diverse range of tools and methodologies, and consultants, have been used to try to assess human capital (e.g. DISC or 360-degree assessments). The criticality of the team is something InnoEnergy emphasized from its inception and triggered the development of a methodology for specifically assessing this aspect. This methodology, InnoEnergy E2Talent®, is used to assess entrepreneurial competencies in early-stage start-ups. Through different exercises, E2Talent® concentrates on those human competencies that have proven important for the success of start-up teams. Specifically, seventeen different competencies are measured with E2Talent® but we will concentrate here on the most critical competency identified by InnoEnergy’s research: achievement motivation.

Achievement motivation is the desire or tendency to do things rapidly, efficiently and/or as well as possible. It also includes the desire to accomplish something challenging or difficult and to meet or surpass a standard of excellence. It implies an urge to measure outcomes against goals, innovate to improve, and take calculated risks to do something new or better. As a potential drawback, people with very high levels of achievement motivation will do everything in their hands to achieve what they want, even if it means bending or breaking rules and laws. Regardless, having a founding team with high achievement motivation has proven a good proxy to assess potential start-up success.

In addition to pure team metrics, related aspects, such as intention (e.g. Krueger et al. 2000) and motivation (e.g. Turkina and Thai, 2013) are critical aspects linked to start-up success. For instance, a motivation to grow quickly, in opposition to slow growth, makes it easier to convince venture capitalists to invest in start-ups, and eventually increases probabilities to survive and potentially succeed. Moreover, and as already mentioned, there might be different conceptions of success in founding teams with more than one member. In this regard, alignment on intentions and motivations are critical to avoid future conflicts linked to confronting views (e.g. growing quickly to sell to a corporate VS building a family business).

Network and Open Innovation

Networks have for long been regarded as critical for innovation in general (e.g. Powel and Grodal, 2005), are known to be relevant for investment processes (e.g. Laubacher, 2012) and are crucial as a source of new ideas and resources (e.g. Chesbrough, 2003). Moreover, networks are related to higher start-up performance and relationships (Startup Genome, 2018). Due to their importance for early survival and for future expansion and internationalization, personal and professional networks have been a recurrent topic in academic research (e.g. Johansson and Vahlne, 2009; Lyles et al. 2004; Mollick, 2014). Moreover, open innovation has also been highlighted as a way by which start-ups can overcome their limitations (e.g. Spender et al. 2017) by capitalizing on external ideas and identifying external paths to market (Chesbrough, 2003).

Discussion and Conclusion

In our current context, some of these factors are becoming more relevant than ever. As we have already seen, start-ups suffer from a variety of liabilities posing an incredible burden on their shoulders and the present situation is only likely to accentuate them even more.

As a starting point, cash is king, especially for early stage start-ups

As a starting point, cash is king, especially for early stage start-ups. These start-ups are almost by default non-profitable and even minor disturbances in their sales and, more importantly, their likelihood to secure funding rounds, can be the difference between death and survival. This is of major importance because, under the negative economic situation we have ahead of us, we might be losing promising start-ups just because of a delay in securing funding. An even increased uncertainty is likely to delay investment decisions even more and this will pose an incredible risk on our start-ups. External public aid mechanisms, like the ones we already start hearing about, will most likely be necessary to soften the decrease on private investment.

Also, in this context, timing is once again crucial. It comes without saying that deciding on when products will be released is of major importance and some product categories might even benefit from this severe situation (teleworking solutions or mobile phone games to name a couple). Moreover, we are likely to see changes in business models like decisions including reshoring in order to guarantee operations for both start-ups and larger enterprises.

It is also relevant to keep an eye on how this situation affects future globalization dynamics both for start-ups and for larger companies. As we move forward in the crisis, we will need to see how/if the start-ups will be able to reach international markets. How much of the start-ups’ demand is coming from these international markets is something that will have a major impact in their likelihood of survival.

Moreover, Customer Acquisition Cost is likely to increase and, in general, while fixed costs will be kept the same, acquiring revenues and funding will become more challenging. In this situation, a strong team and a strong network of partners and people, are likely to become even more crucial than before.

To conclude, we have an extremely uncertain path ahead of us and start-ups will be put under severe pressure. An individual, thorough, review of the factors mentioned above will be needed to identify strengths and weaknesses to help start-ups survive. Public help will also be necessary. Hopefully by capitalizing on the strengths, and recognizing the weaknesses, promising start-ups can navigate through this economic turmoil and have a chance to prove their value and, potentially, succeed in the start-up arena.

About the author

Currently working as Innovation Ecosystem Manager at EIT InnoEnergy (Spain) and as a visiting fellow at Turku University of Applied Sciences (Finland), Alberto Gonzalez is an experienced manager, qualitative researcher and educator.

His fields of expertise revolve around Innovation Management and range from Sustainable Development to Design Thinking and from New Product/Service Development to Creativity Tools. He has extensive international experience having lived abroad and/or worked extensively with international partners and with projects/visits in markets such as Spain, Finland, Nepal, GCC, Russia, Ireland and The Netherlands among others.

Alberto is personally passionate about innovation and education and interested in projects related to sustainable development, digitalization, l&d, transformation through design thinking and innovation and innovative teaching methods and pedagogy. On a different level, he has an interest in academic research in the fields of customer involvement in product development, learning processes, co-production and knowledge transfer, especially in the field of the creative industries.

Bibliography

Bianchi, M., Campodall’Orto, S., Frattini, F. and Vercesi, P. (2010) Enabling open-innovation in small- and medium-sized enterprises: how to find alternative applications for your technologies. R&D Management, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 414-431.

Chesbrough, H. (2003) The Era of Open Innovation. MITSloan Management Review, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 35-41.

Coad, A., Frankish, J., Roberts, R.G. and Storey, D.J. (2013) Growth paths and survival chances: An application of Gambler’s Ruin theory. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 28, No. 5, pp. 615-632.

Dimov, D.P. and Shepherd, D.A. (2005) Human capital theory and venture capital firms: exploring “home runs” and “strike outs”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 1-21.

Ebert, T., Brenner, T. and Brixy, U. (2019) New firm survival: the interdependence between regional externalities and innovativeness. Small Business Economics, Vol. 53, pp. 287-309.

Freeman J., Carroll G.R. and Hannan M.T. (1983) The liability of newness: age dependence in organizational death rates. American Sociological Review, Vol.48, No.5, pp.692-710.

Honjo, Y. (2000) Business failure of new software firms. Applied Economics Letters, Vol. 7, No. 9, pp. 575-579.

Hopp, C. and Sonderegger, R. (2015) Understanding the Dynamics of Nascent Entrepreneurship – Prestart-Up Experience, Intentions, and Entrepreneurial Success. Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 53, No. 4, pp. 1076-1096.

Johansson, J. and Vahlne, J. (2009) The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited. From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 40, pp. 1411-1431.

Khan, Z. and Lew, Y.K. (2018) Post-entry survival of developing economy international new ventures: A dynamic capability perspective. International Business Review, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 149-160.

Kato, M. and Honjo, Y. (2015) Entrepreneurial human capital and the survival of new firms in high- and low-tech sectors. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, Vol. 25, pp. 925-957.

Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D. and Carsrud, A.L. (2000) Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 15, No. 5/6, pp. 411-432.

Laubacher, R. (2012) Entrepreneurship and venture capital in the age of collective intelligence. MIT Center for Collective Intelligence, Working Paper No. 2012-02.

Lyles, M.A., Saxton, T. and Watson, K. (2004) Venture Survival in a Transitional Economy. Journal of Management, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 351-375.

NASA. (2012). Technology Readiness Level. Available online at https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/heo/scan/engineering/technology/txt_accordion1.html. Accessed March 6, 2020.

Mollick, E. (2014) The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 1-16.

Pitkänen, I., Parvinen, P. and Töytäri, P. (2014) The Significance of the New Venture’s First Sale: The Impact of Founders’ Capabilities and Proactive Sales Orientation. Journal of product innovation management, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 680-294.

Powell, W. and Grodal, S. (2005) ‘Networks of Innovation’, in Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D. and Nelson, R. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Innovation, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Quintero, S. (2017) Dissecting startup failure rates by stage. Medium – Journal of Empirical Entrepreneurship. Available online: https://medium.com/journal-of-empirical-entrepreneurship/dissecting-startup-failure-by-stage-34bb70354a36 Accessed February 28, 2020.

Spender, J., Corvello, V., Grimaldi, M. and Rippa, P. (2017) Startups and open innovation: a review of the literature. European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 20, No.1, pp. 4-30.

Startup Genome (2018) Global Startup Ecosystem Report. Startup Genome.

Stinchcombe A.L. (1965) Social structure and organizations, in J.G.March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 142–193), Chicago:RandMcNally.

Taleb, N. N. (2007). The Black Swan: the impact of the highly improbable. London: Penguin.

Turkina, E. and Thai, M.T.T. (2013) Social-psychological determinants of opportunity entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Vol. 11, pp. 213-238.

Usman, M. and Vanhaverbeke, W. (2017) How start-ups successfully organize and manage open innovation with large companies. European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 20, No.1, pp. 171-186.