Eri tutkimuksissa taiteen on havaittu parantavan hoitotuloksia, vähentävän fyysisiä ja psykologisia oireita sekä vaikuttavan positiivisesti hoidon laatuun ja hoitohenkilökunnan työhyvinvointiin….

Tekijät | Authors

Mapping music and well-being in the Finnish context through music practitioners’ work and educational views

In what ways have innovative music and well-being practices emerged in Finnish contexts during recent decades? What kind of educational views have taken place? In the following, the authors reflect these questions.

Last week, one of our hospital music students told me, when we were discussing her internship in community musician studies: “I was recently asked to assist a palliative care nurse in her work at home of a deathly sick child and his family. Do you think I could take that as a part of my studies?”

I, as her tutor, was speechless for a while. Speechless seeing the challenge for this young musician, speechless with respect for her being asked for it, speechless with the image of the especially delicate and sensitive situation in a setting like that. I was also speechless with joy that an approach like that would really be a possibility in Finland, now, and for our students, in the developing interprofessional field of music and health.

Historical views on music and well-being in Finland

“Sleep, sleep, little grassland bird, A tired, so tired, white wagtail. Sleep well in the grass, lay down on the good earth.” This ancient, traditional Finnish lullaby, originally to mourn the death of a child, leads us in reflecting the area of contemporary Finnish music, health and well-being. The poorest and unequal country of Europe, Finland, had those days many societal challenges, e.g. high-level infant mortality, low education status of citizens and serious societal conflicts. After achieving independence in 1918, within one century, Finland has become a modern welfare state offering high level well-being for its citizens and reportedly also to other countries.

Gentle and soothing music for the little one. Musicians: Sanna Vuolteenaho and Emmi Kuittinen. Photo: anonymous by request.

Constructing a welfare state was a conscious political and societal movement that was implemented after World War II despite the wide post-war poverty in the whole country. These societal and political efforts reveal contemporary values emphasizing culture in the society as a consistent, continual storyline instead of arbitrary, haphazard actions. Hence, to acknowledge that culture is fundamental to human dignity and identity, as well as to participate in arts is a cultural right that should be available for all via lifelong learning, needs constant, continuing work for equality and work against exclusion.

As Unesco (2019) has stated, arts, in this case music, are for all. Following this visionary ethos the UN Declaration of Human Rights, article 27, is stating that “everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits”. This is also a situation, at least in theory, in many other countries nowadays.

However, the contemporary Finnish society, as other western societies, is facing many challenges and problems considering globalisation, integration, digitalisation, and the growing sustainability gap. In favor of presenting innovative solutions implemented to settle the unequal societal circumstances, this article reflects emerging music and well-being practices, education, and research that has been taking place in the Finnish context during the recent decades.

Innovative collaborations within arts and welfare services

To ensure social innovations to take place in the future, this article presents some uncovered views in the area of music, naturally the highly flexible and fragmented field in mind. The underpinning theoretical frame here is to understand music and well-being as a highly complex entity that acknowledges the possibilities of well-being to take place within active and social music making, listening, or being inclusively part in music practices. This means that well-being aspects are experienced in, through and with music and musical interaction.

At the same time, this frame entails a notion that music and arts do not self-evidently provide us positive experiences. Instead, music offers us highly individual and relative means when it comes to well-being issues. In search to understand this diversity, it is important to comprehend the area of music, health and well-being, intertwining quite often with great desires and aspirations about healing with music, which possibly cannot be fulfilled within the frame of music and well-being.

When this kind of interdisciplinary, cross-sectoral area is emerging and developing, it calls for relevant policy gap(s) and the interest of many kinds of stakeholders. In Finland, cross-sectoral governmental collaboration has taken place until 2008, and after conducting a five-year Finnish Art and Culture for Well-being program in 2010-2014, the visions of combining the political, administrative and structural commitments in the area have continued.

Besides that, it has required a lot of active undertaking, agency, and even activism of individual scholars, musicians, music educators, music therapists and other practitioners to promote music, health and well-being with other art forms in an inclusive manner. This activity, rooting from e.g. the autonomy of Finnish teachers and high level of education, has enabled individuals, teams, projects, stakeholders, and policy makers in many levels to become involved in this silo-breaking work.

One example of collaboration and continuing work for integrating the field of inclusion, participation and health promotion through arts is Taikusydän (2019), “a multisectoral coordination and communication center for activities and research among the field of arts, culture and wellbeing”. Taikusydän was originally organised to promote the objectives and proposals of the Art and Culture for Well-being program. The center drives through making arts and culture a permanent part of well-being services, to promote interdisciplinary and multiprofessional research and practice, and to create networks and develop evidence-based practices.

Finnish actor Jussi Lehtonen (2015, 13) has relevantly in his doctoral dissertation, concerning actors working in prisons and care homes, asked: “How many artists are able to give a healthcare guarantee of the results of their work? Aren´t the people in care homes deserving art in their living environments, like anybody else, without instrumental epithets that are defined from the outside?” In favor of turning the classical “clinical gaze” from ill-being to well-being, we are obliged to remember not to do the opposite with non-reflexive practices. Would this turn music and well-being into music and ill-being, as Avanti! Chamber Orchestra critically in their concert, in 2016, asked: “The affluent society feels sick, but would art help? Allocations for culture are cut, but in ´care arts´ they invest in. May care music be played in the minor, or, should it be harmless and simple? Or doesn’t just independent and free art represent well-being, does it?”

Reflections on the practice of music and well-being

Care music and music in other well-being settings, such as hospitals, took a wider space in Finland in 2010s. Through projects and other initiatives the practices were developed and innovated. Petteri Siika-Aho (2013, 184), project manager of the Care Music Project, defined care music to be actions as follows: music work that is linked both to music and care; taking care of others with the aims of music; and interactive action that sets naturally strong musical objectives.

Sharing a song. Musician Iida-Maria Uljas. Photo: Jaana Horppu.

You could say that the concept of care music is in a way conflicting and contradictory. Musical care may support care and help individuals to be objected to care overall especially in facilities, but at the same time it can give people a possibility to extend their capabilities, autonomy, lifelong learning and independency. Working in healthcare and specialised healthcare services (e.g. in hospital wards) takes music and care to another level, where music is situated in highly institutionalised care. In the same healthcare environments we may find performing musicians giving concerts, music therapists working through rehabilitative and therapeutic frameworks, healthcare musicians visiting in single rooms and wards, and personnel conducting music and medicine practices and having training in music and health, as well as music and well-being issues (see case Espoo City Hospital 2019).

Making music with and for people

It seems that professional music and well-being practices will not be an area that will create certificated, strong professions like e.g. music therapy or other healthcare professions. However, this does not mean that no training is taking place, and overall, music practitioners working in healthcare seem to be highly educated. To practice music in healthcare refers to engaging with highly sensitive and reflexive activity. Here it is argued, that in favour to nourish rich and innovative dialogue between different collaborators, the concepts do not need to be cemented and they can be in constant, transformative process.

There is music in the air. Musician: Anna-Maaria Varonen. Photo: Uli Kontu-Korhonen.

What kind of professional practices should a musician, music educator, or for example an ethnomusicologist, apply when one enters in the care or healthcare environment? Instead of thinking of the repertoire or single productions one could ask, how and why you make music with and for people. In what ways are you encountering others? “And yet, the professionalism of the hospital musician is formed and refined from the strengths of each artist or music educator. There is no one kind of hospital musician or hospital music”, states one of the pioneers and leading trainers in the field of healthcare and care music in Finland, Uli Kontu-Korhonen.

Music and well-being within the umbrella of arts, health and well-being

Professional music practices in the framework of music and well-being could be considered from several angles:

The community point of view stems from the principle that music and other arts are human rights that are a crucial part of meaningful, good life. From the interprofessional viewpoint, there is a wider understanding of the multiprofessional approaches` possibilities in diverse operating environments, for example in healthcare.

In the core of integrative approach is musical expertise incorporated with social and healthcare sectors as well as acknowledging the interdisciplinary possibilities and challenges. The best practices and ethics of the social and health care can be combined with the best practices and ethics of music and arts, including dialogical and reflective working attitudes of professionals.

The societal impacts in the field may, according to our viewpoint, have a wider significance in the comprehensive well-being of individuals, their cultural capital and sustainable development of the society. This may create new, even paradigma-level prospects for working life concerning health and well-being practices, as well as for the workforce in wider societal and cultural fields.

Mapping professional music practices in care and healthcare

Foundations and facilitators of music practices in care and healthcare are presented in Figure 1: Professional music practices as facilitators of music and well-being in care and healthcare.

Figure 1: Koivisto & Lilja-Viherlampi 2019: Professional music practices as facilitators of music and well-being in care and healthcare.

Educational and institutional collaboration in music and well-being

The educational perspective is crucial in developing the field of music in health and well-being contexts. In the following, we present some educational institutions and organisations which have contributed to the visions, practices, and research in Finland.

From one point of view, a fruitful perspective is engaging in training related to the construction of each individual’s personal relationship to arts. A start may be a music playschool offered for large populations in Finland. The education will then continue in the child´s (musical) lifespan with potential (music) hobbies, or later on in vocational training, or in higher education. The basic arts education system (BAE), elementary school art classes and various informal activities may offer opportunities to build a personal music relationship and musical, as well as other, competences that are required in the field.

From another point of view, education can be considered as a professional learning of many kinds of skills and competences. By that professional view students, studying arts or arts-based working methods, learn to open up for other peoples` experiences, linked with their own relationship to arts. In practice, e.g. a music educator or music pedagogue is aware of, and applies the therapeutic meanings and potentials of music and musical interaction. Or, referring to a theatre instructor student, learning to facilitate people’s self-expression through drama. Or, a social services student is learning to use functional and arts-based methods. These frames can be utilised for example to facilitate the social work processes through enhancing clients’ creativity. Thus, professionals gain personal experiences and understanding of their own relationship to music and other arts approaches, and learn to apply them in their work.

The third point of view is framed by a question of the mindset the trainees, students, teachers and multiprofessional sectors involved, are possessing – what are the goals of the education in terms of interprofessional interfaces? What will be the prospects, the future working environments, in relation to the basic function of the work of future music practitioners? What role is the training in arts, health and well-being work taking in relation to this basic task? In this case, different levels of education could be considered: basic education (secondary or BA level), higher education in the arts (MA level), in-service training and continuing education in the work. However, the contents and training of the future professionals in all these levels should be considered in a more systematic manner. When regarding the global, as well as local, transformation of societies and functions of work and professionalism, the education in the boundaries of social, healthcare and the arts sectors should be considered carefully.

Integrating music and well-being with education: Visions of life-long learning

The construction of the Finnish welfare state entails basic education system, including by and large the whole population in public schooling, and has led to integrating arts education in the schools and their curricula. The state of the art in Finland has been that the education of music and well-being has been integrated in the existing educational programmes. Hence, the education as well as implementing the practices has been so far more or less fragmented and occasional. However, many parties from third sector organisations to basic arts education institutions, and from the ministries to vocational and higher education establishers, have been interested in developing the field.

In the field of healthcare and social sector education, there is a growing interest for applying arts-based approaches, but it’s definitely not yet mainstream. Various pilot projects have been conducted but the development work has often been bound to project fundings and sometimes with no continuity after the project is finished. Fortunately, the more the projects make sequels, and are integrated to the cooperation between the working life and the education, the more the developmental steps go forward.

As an example of this kind of continuum is a Community Musician Specialisation study program financed by the Ministry of Education and Culture 2017–2019. The Ministry launched a national program involved with six universities of applied sciences. At Turku University of Applied Sciences, the profile of the studies has been Hospital and Care Music, something new for experienced music practitioners.

And, as an example of continuation at Turku University of Applied Sciences, applying music approaches and benefits in a variety of environments, specialisation studies in music therapy have taken place, both included in the BA degree programme of music pedagogy (2000–2002) and as continuing education for the professionals in the field of education (2000–2003). Within the programs, students studied therapeutic meanings and possibilities of music and musical interaction and applied them into their professional orientation.

Education in music and well-being could be described as a life-long continuum linking to the basic essence of the human world of experiences. Human beings could be understood as “arts-receptive” from “womb to tomb”. The first musical experiences of a fetus are experiences of voice and rhythm and the tone of speech. One could consider voice or sounds to be the last sensations of the world of experiences, which human beings receive in transition to death. The possible life-long relationship to arts links with the versatile basic elements of the human world of experiences. In addition, these experiences grow and develop when we are absorbing the elements of the surrounding environments. It could be thus argued that

the very heart of education in the arts, health and well-being field is the human´s personal relationship to arts; it is where the education is embedded and reflects itself.

Mapping some research in the field of music and well-being in Finland

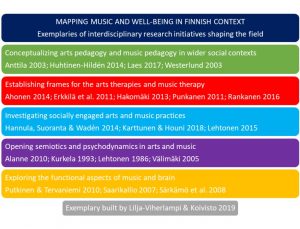

Understanding the phenomena at hand requires and, at the same time, challenges interdisciplinarity. There is no one field of research that would thoroughly explain the multifaceted phenomena of the human relationship to music. Following, referring to the diversity of researchers and their interests, some examples that have had an impact on the Finnish discussion, as well as the reflections of the authors in this article, are given in the format of Figure 2.

Figure 2: Lilja-Viherlampi & Koivisto 2019: Exemplaries of the variety of interdisciplinary research that has shaped the discussion in the field of music and well-being in Finland.

A narrative within Maija’s relationship to music along her life-span

In the following, an image of Finnish education is built through an educational, fictional narrative of a person called Maija. This story demonstrates Maija’s path in her life assuming Maija as a professional of music. Maija has a variety of possibilities to foster her musical experiences. This story is an example of the possibilities of lifelong education – in this case, in music. Maija is an imaginative person constructed from many kinds of music educational opportunities in Finland. The viewpoint here reflects primarily the principles of the Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences in facilitating lifelong education, one of the basic tasks in this educational level. The authors wish not to embrace without criticism the context, but to demonstrate the educational possibilities, present and future views in the field of practising music, as well as other arts.

Maija’s story

Before her birth, not-born-yet Maija and her mother-to-be already attended a music group for pregnant mothers, held by a professional music pedagogue specialised in early childhood music education. Maija’s mother-to be was informed about it by the public maternity clinic. So, after Maija was born we could think she already had a psycho-physical core self, which was elementarily affected by a rich variety of core experiences of music and its elements. There had been rhythms, forms, pitches, human voices and various kinds of music resonating in the womb. Maija’s parents continued with her in a music playschool for babies. Joyful music playschool sessions occurred once a week and Maija’s parents continued with her, singing and playing at home the songs learned at the playschool. Maija grew with music and experienced her self-expansion in the (musical) interaction…

Maija’s musical storyline continued with playful music lessons – from a four-year little girl. She started preliminary training with piano, and soon Maija was ready to begin the regular studies in her instrument in the comprehensive music education system.

On the other hand, at primary and later secondary school, Maija had music education once a week. According to a new curriculum, Maija’s teacher applied the phenomenon-based approach, and the class viewed the world multi-disciplinarily, also from the musical perspectives (Maija’s teacher was specialised in music education during her elementary education studies). Maija attended the school choir, and there was additionally a chance to join a band after the school day, with her friends. Maija gained more and more experience in music, musical expression, performance, collaboration in, with and by music and among audiences…

So, Maija grew up in music, with music and by music: during her years of growth, Maija’s musical self transformed and actualised through the positive interaction and musical enculturation, ie. in the meaning of assimilating the qualities of her musical surroundings.

Maija was so intensively keen on music that she chose to seek a music professional career after graduating from college. At the same time, she got her diploma from the studies at conservatory, which had followed her years at the music school. Then, after four years, she graduated in music pedagogy from one of the Universities of Applied Sciences. Maija’s musical skills were refined to the professional level: understanding of music, performance, and musical interaction; teaching music; pedagogical interaction. Additionally, during these studies, Maija’s teacher had guided the students to have concerts in a variety of environments, such as elderly care homes. In her optional studies, Maija was able to execute a pedagogical project tutored by her teacher, taking place at a local hospital, children’s ward. During her studies at the multidisciplinary and multi-art university she was able to experiment projects with students from other arts disciplines. Music and devising puppet theater were a success in intergenerational occasions, such as with senior citizens and children.

After graduation, Maija was working at a music school with a new generation of pupils. There she worked among individual people and various ensembles. Built by her own experiences, Maija organised concerts with her students in the nearby nursing home. Within the framework of the daily work she was provided with inservice training. She could attend to workshops on group dynamics, music therapy and audience outreach work, since in Finland inservice training has a strong focus in the professional development of a teacher.

Soon an interest to expand her professional views began to sparkle in Maija. Three years of working life after BA graduation, and Maija could apply for a Master’s Degree at her alma mater. There was an interesting possibility available for her: A course on Contemporary Contexts of Arts. New worlds and discourses opened up there: applying arts, interprofessional working, multidisciplinary teamwork. She learned to apply her competences more consciously within new connections and operative environments, and practise community arts. Maija built her development project within seniors’ music education. During her studies, she actively participated in the multidisciplinary (arts, social and health sector) research group on Arts, Health and Well-being that was operating dynamically at her study unit. In her optional studies, Maija continued to work with a theater artist at the children’s ward at the local university hospital. Luckily there was also a doctoral student who observed Maija’s work and with whom she had inspiring discussions. Maija was growing in her knowledge and skills as an expert and developer.

After completing her master’s degree, Maija was involved in a nationwide project to study and develop the education for and with senior citizens, where she was able to collaborate with researchers at the university specialized in the arts. In her work at music school she was working increasingly with adult students and at the same time, she began systematically develop music activities and late adulthood music education in a seniors´community house nearby.

Later on, Maija’s lifelong education progressed simultaneously with her daily work on its track. She attended a Community Musician specialisation training. The profile of the studies was a musician in hospital and nursing environments. In a development project, Maija reflected her own professional transformation into a community musician frame; observing, reflecting and analysing her time in an artistic residence at a nursing home. Maija could have 2 months off work due to the Finnish adult education funding system.

Maija’s working field was now even more enriched and expanded, including music education work, developer work in a research project, and part-time work as a musician at a nursing house. She was asked to train the nursing staff there, and she was happy to give them demonstrations on how to apply music in daily life of the community. She also facilitated possibilities to promote the well-being of the residents by and with music. One important aspect was to promote the interprofessional cooperation between various kind of music professionals; musicians, music pedagogues and music therapists – and social and health care professionals.

Maija was very energetic by nature and eager to learn more. So, after a few years, Maija started her doctoral studies in a university´s research project. Regarding her studies, she developed a theoretical and practical framework for nationwide senior music education. She completed her doctoral studies as a researcher-developer in the field.

Her field at work expanded with new tasks. Maija acted as a part-time teacher at a University of Applied Sciences; there she promoted the understanding of the human musical relationship with both the arts students and the social and health care students. She participated as an expert in an European RDI project, developing multi-professional art-based collaboration and further education among arts and social sector students.

Maija had lived a rich life musically so far and given much to others. When she retired at the age of 65, she still wanted to learn more. She began to take classes in jazz and improvisation in an open-access classes of a conservatory, and got enthusiastic about them in her ”old days”.

… and Maija’s life-span as a learner and as a music person went on in her life; in her family and in her multiple networks. She was a well-requested senior expert in different contexts and collaborations.

After twenty years of “retired” life full of joy and inspiration of music, a tough phase started: Maija was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Despite of the circumstances, she was able to live at her own home for a long time: she received there the services needed, including community musician’s services – as a fruitful result of the work Maija had promoted in times of her active career! This brought a lot of joy and hope to her life despite of the severe illness and she even considered attending a rock band for the third age ladies…

Eventually, it was time for Maija to move into a nursing home. As part of the services, Maija’s relationship to culture and arts was mapped and the possibilities to support her engagement and accessibility in arts were facilitated. Musicians visited regularly in the care home and this supported Maija in providing her own skills in the music life of the care home. Despite of the Alzheimer’s, Maija could still delight both herself and others with her music!

Maija could live in the nursery home further on, even when it was time for hospice care, where she received her last experiences from music, especially human voice. The hospital musician visited Maija regularly and encouraged the staff to sing and take into account the surrounding music and voices, when Maija was to stay in bed all day long. A music therapist was available, helping Maija significantly with music therapy methodology during the moments of anxiety.

Finally, Maija’s family was singing around Maija by the bed when her life here came to an end… “Sleep, sleep, little grassland bird, A tired, so tired, white wagtail. Sleep well in the grass, Lay down on the good earth.”

In the end of the day – mapping the future

This article has been an intervention in the discussion that is going on both internationally, and in contemporary Finnish society. On the one hand, there are the critical needs to find social innovations for sustainable development of societies and develop new approaches in the renewing fields of social sector and health care, as well as other societal sectors. And on the other hand, there are the inspiring possibilities of acknowledging the full capacities of art-based approaches.

The work in opening up the interfaces and shared interests within the fields of social sector, healthcare sector and arts sector has only just begun. In the future, there are lots of interesting practices and ways to promote interdisciplinary cooperation to be found. The meanings and potentials of music are constantly gaining more and more evidence for knowledge bases that may prove music even an indispensable means of promoting health and well-being in the future.

The Ministry of Education and Culture in Finland has recently released a report (2018) revealing the policies in arts and emphasising the following themes: 1) Art should be in the very core of society 2) To develop economic strategies in the art fields is an important task in the future, and 3) Art is work, and it should be encountered as such.

Though participation in early childhood music education is rather high in Finland, many people are being excluded from enjoying arts or arts education in all ages. The accessibility of music education or music services overall does not depend just on economic issues, as one would easily consider. Consequently, the accessibility being ostensibly open, the education does not reach all socioeconomic groups of the population. As was presented earlier, arts as a lifelong cultural right and a profession needs constant, continuing and visionary work for equality and – work for offering well-being for us all.

This publication has been undertaken as part of the ArtsEqual project funded by the Academy of Finland´s Strategic Research Council from its Equality in Society programme (project no. 293199).

References

Ahonen, H. 2014. Adult Trauma Work in Music Therapy. In Edwards, J. (ed.) 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Music Therapy. Oxford: University Press, 268–289.

Ahonen, H., & Houde, M. 2009. Something in the Air: Journeys of Self-Actualization in Musical Improvisation. Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy, Vol 9, No 2. Retrieved in March 6, 2019 https://doi.org/10.15845/voices.v9i2.348.

Alanne, S. 2010. Music Psychotherapy with Refugee Survivors of Torture: Interpretations of Three Clinical Case Studies. Doctoral Dissertation. Helsinki: Sibelius Academy. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-5531-88-6.

Anttila, E. 2003. A Dream Journey to the Unknown: Searching for Dialogue in Dance Education. Doctoral Dissertation. Theatre Academy. Helsinki: Acta Scenica. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 http://hdl.handle.net/10138/33789.

ArtsEqual. 2019a. The Arts as Public Service: Strategic Steps towards Equality. Retrieved in March 13, 2109 http://www.artsequal.fi/en.

ArtsEqual. 2019b. ArtsEqual Policy Brief: Accessibility in the Finnish Basic Education in the Arts Retrieved in March 24, 2019 http://www.artsequal.fi/-/toimenpidesuositus-taiteen-perusopetuksen-saavutettavuus.

Avanti! 2016. Hyvinvointitaide – Pahoinvointitaide. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 https://www.kaapelitehdas.fi/tapahtumat/2016/avanti-hyvinvointitaide-pahoinvointitaide.

Bonde, L. O. 2011. Health Musicing – Music Therapy or Music and Health? A Model, Empirical Examples and Personal Reflections. Music & Arts in Action Vol 3, No 2, 120–140. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.464.4119&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford: University Press.

Clift, S. & Camic, P. 2016. The Oxford Textbook of Arts, Health and Well-Being: International Perspectives on Practice, Policy, and Research. Oxford Texbooks in Public Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

DeNora, T. 2016. Music Asylums: Wellbeing through Music in Everyday Life. New York: Routledge.

Erkkilä, J.; Punkanen, M.; Fachner, J.; Ala-Ruona, E.; Pöntiö, I.; Tervaniemi, M., Vanhala, M. & Gold, C. 2011. Individual Music Therapy for Depression: Randomised Controlled Trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Vol 199, No 2, 132–139.

Espoo City Hospital. 2019. City of Espoo. Recovery and Art in Espoo Hospital. EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Arts, 54/2017. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 https://www.espoo.fi/download/noname/%7B43029327-3AF3-43BD-ABDC-ED638529E3BF%7D/85160.

European Union 2019. Structuralfunds.fi. European Regional Development Fund and European Social Fund. Retrieved in Feb 24, 2019. http://www.rakennerahastot.fi/web/en/home?p_p_auth=VrnIr1Mt&p_p_id=77&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=maximized&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_pos=2&p_p_col_count=3&_77_struts_action=%2Fjournal_content_search%2Fsearch.

Foucault, M. 1963. The Birth of the Clinic. London: Routledge.

Foster, B. & Bartel, L. 2016. Understanding Music Care in Canadian Facility-Based Long Term Care. Music & Medicine. Vol 8, No 1, 29–34.

Gielen, P. 2009. The Murmuring of the Artistic Multitude: Global Art, Memory and Post-Fordism. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Gómez Ciriano, E. J.; Herranz de la Casa, J.M.; Kivelä, S.; Gibson, J.; McLaughlin, H.; Lilja-Viherlampi, L.-M.; Männamaa, I. & Araste, L. (eds.) 2018. Handbook for Moving Towards Multiprofessional Work. Course Material from Turku University of Applied Sciences 113. Turku: Turku University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 http://julkaisut.turkuamk.fi/isbn9789522166777.pdf.

Hakomäki, H. 2013. Storycomposing as a Path to a Child’s Inner World: A Collaborative Music Therapy Experiment with a Child Co-Researcher. Doctoral Dissertation. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities, 204. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/41513/978-951-39-5207-5_vaitos27052013.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Hannula, M.; Suoranta, J. & Vadén, T. 2014. Artistic Research: Methodology. New York: Peter Lang.

Huhtinen-Hildén, L. 2014. Perspectives on Professional Use of Arts and Arts-Based Methods in Elderly Care. Arts & Health. Vol 6, No 3, 223–234.

Karttunen, S. & Houni, P. 2018. ArtsEqual 2015-2021: The Challenges of a Large-Scale Research Initiative in Finland. Conjunctions. Transdisciplinary Journal of Cultural Participation. Vol 5, No 1, 1–11.

Koivisto, T.-A. 2018. The Emerging Space of Music Education in Healthcare: Towards a Holistic Conceptualisation of Purpose and Professionalism. The Finnish Journal of Music Education. Vol 21, No 1, 68–74.

Koivisto, T.-A.; Tähti, T. & Lehikoinen, K. Forthcoming. Exploring Music Practitioners´ Hybrid Professional Space in Hospitals through a Qualitative Systematic Review.

Kurkela, K. 1993. Mielen maisemat ja musiikki: musiikin esittämisen ja luovan asenteen psykodynamiikkaa. Helsinki: Sibelius Academy.

Kontu-Korhonen, U. 2019. Musiikin ammattilainen sairaalamuusikkona. In Lilja-Viherlampi (ed.) 2019. Musiikkihyvinvointia! Musiikkityö sairaala- ja hoivaympäristöissä. Turku: Turku University of Applied Sciences (in publication process).

Laes, T. 2017. The (Im)Possibility of Inclusion: Reimagining the Potentials of Democratic Inclusion in and through Activist Music Education. Doctoral Dissertation. University of the Arts Helsinki, Sibelius Academy. Studia Musica 72. Helsinki: Unigrafia. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/235133/nbnfife201705096359.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Lehikoinen, K. & Rautiainen, P. 2016. ArtsEqual Policy Brief 1/2016. Cultural Rights as a Legitimate Part of Social and Health Care Services. Retrieved in March 13, 2109 http://www.artsequal.fi/documents/14230/0/PB+Art+in+social+services/b324f7c4-70e3-4282-bc77-819820b9a6d4.

Lehtonen, J. 2015. Elämäntunto – näyttelijä kohtaa hoitolaitosyleisön. Doctoral dissertation. University of the Arts Helsinki, Theatre Academy. Acta Scenica 42. Helsinki: Edita Prima Oy. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/156950/Acta_Acenica_42.pdf?sequence=1.

Lehtonen, K. 1986. Musiikki psyykkisen työskentelyn edistäjänä: psykoanalyyttinen tutkimus musiikkiterapian kasvatuksellisista mahdollisuuksista. Doctoral Dissertation. Turku: University of Turku.

Liikanen, H. 2010. Art and Culture for Well-Being: Proposal for an Action Programme 2010–2014. The Ministry of Education and Culture in Finland 2010:9. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 http://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/75529/OKM9.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Lilja-Viherlampi, L.-M. 2007. ”Minunkin sisällä soi!” – musiikin ja sen parissa toimimisen terapeuttisia merkityksiä ja mahdollisuuksia musiikkikasvatuksessa. There is a sound in me” – about the therapeutic meanings and possibilities of Music and Musical interaction in music educational context. Doctoral Dissertation. Turun ammattikorkeakoulun tutkimuksia 24. Turku: Turku University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 http://julkaisut.turkuamk.fi/isbn9789522166647.pdf.

Lilja-Viherlampi, L.-M. 2012. Taidetoimintaa vai terapiaa. Sairaala- ja hoivamusiikkityön lähtökohtia ja kehitystyötä. UAS Journal 1/2012.

Lilja-Viherlampi, L.-M. (ed.) 2013. CARE MUSIC: Sairaala- ja hoivamusiikkityö ammattina. Turun ammattikorkeakoulun raportteja 158. Turku: Turun University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 http://julkaisut.turkuamk.fi/isbn9789522163660.pdf.

MacDonald, R.A.R.; Kreutz, G. & Mitchell, L. (eds.) 2012. Music, Health, and Wellbeing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marjanen, K. 2009. The Belly-Button Chord: Connections of Pre- and Postnatal Music Education with early Mother-Child Interaction. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Jyväskylä. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities 130. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Printing House. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/22602/9789513937690.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Musique Santé. 2018. European network of “Music in Healthcare Settings”. Retrieved 11.11.2018 http://www.musique-sante.org/en/projets-en-europe/european-network-%E2%80%9Cmusic-healthcare-settings%E2%80%9D.

Nuku, nuku, nurmilintu. Sleep, Sleep, Little Grassland Bird. 2019. Lyrics Translate. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 https://lyricstranslate.com/en/sleep-sleep-little-grassland-bird-lyrics.html.

Nussbaum, M.C. 2011. Creating Capabilities. London: Harvard University Press.

OECD. 2017. How´s Life in Finland? Retrieved in March 13, 2019 https://www.oecd.org/statistics/Better-Life-Initiative-country-note-Finland.pdf.

Paananen, P. 2003. Many Paths to Music: The Tonal and Harmonic Development of Rhythmic, Melodic and Harmonic Improvisations of 6-11-Year-Old Children. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Jyväskylä. Department of Music. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Press.

Parkinson, C. & White, M. 2017. Inequalities, the Arts and Public Health: Towards an International Conversation. In Stickley, T. & Clift, S. 2017. Arts, Health and Wellbeing: A Theoretical Inquiry for Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Piha, H. 2017. Äänten tulkinta. Näkökohtia auditiivisen kommunikaation varhaissyntyisistä merkityksistä. In L. Klockars & A. Laine (eds.) Äänten antologia. Suomen psykoanalyyttisen yhdistyksen 50-vuotisjuhlakirja. Ntamo: Helsinki, 222–242.

Preti, C. & Welch, G. 2004. Music in a Hospital Setting: A Multifaceted Experience. British Journal of Music Education. Vol 21, No 03, 329–345.

Preti, C. & Welch, G. 2013. Professional Identities and Motivations of Musicians Playing in Healthcare Settings: Cross-Cultural Evidence from UK and Italy. Musicae Scientiae. Vol 17, No 4, 359–375.

Punkanen, M. 2011. Improvisational Music Therapy and Perception of Emotions in Music by People with Depression. 2011. Doctoral Dissertation. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities, 153. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

Putkinen, V. & Tervaniemi, M. 2018. Neuroplasticity in Music Learning. The Oxford Handbook of Music and the Brain. In Thaut, M.H. & Hodges, D.A. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Music and the Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198804123.013.22.

Rankanen, M. 2016. The Visible Spectrum: Participants’ Experiences of the Process and Impacts of Art Therapy. Doctoral Dissertation. Helsinki: Aalto ARTS Books. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-60-6921-0.

Rantala, K. 2014. Narratiivisuus musiikkikasvatuksessa. Tapaustutkimus musiikkileikkikoulupedagogiikasta. About narrativity manifesting itself in music education. Doctoral Dissertation. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Saarikallio, S. 2007. Music as Mood Regulation in Adolescence. Doctoral Dissertation. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-2731-8.

Sahlberg, P. 2014. Finnish Lessons 2.0: What can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland? New York: Teachers College Press.

Shapiro, J. 2002. (Re)Examining the Clinical Gaze through the Prism of Literature. Families, Systems, & Health. Vol 20, No 2, 161–170.

Siika-Aho, P. 2013. Hoivamusiikki ammattina – mahdollisuuksia ja haasteita. In Lilja-Viherlampi, L.-M. (ed.) CARE MUSIC sairaala- ja hoivamusiikkityö ammattina. Turun ammattikorkeakoulun raportteja 158. Turku: Turku University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 http://julkaisut.turkuamk.fi/isbn9789522163660.pdf.

Sutinen, J. 2004. Pitkä matka ja tyhjä reppu – kuolevan toivo ja hengellinen tukeminen kirkon sielunhoidon näkökulmasta. Teoksessa H. Heikkinen; V. Kannel & E. Latvala (eds.) Saattohoito – haaste moniammatilliselle yhteistyölle. Helsinki: WS Bookwell Oy, 75–88.

Särkämö, T.; Tervaniemi, M.; Laitinen, S.; Forsblom, A.; Soinila, S.; Mikkonen, M.; Autti, T.; Silvennoinen, H.M.; Erkkilä, J.; Laine, M.; Peretz, I. & Hietanen, M. 2008. Music Listening Enhances Cognitive Recovery and Mood after Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke. Brain. Vol 131, No 3, 866–876.

Stickley, T. & Clift, S. (eds.) 2017. Arts, Health, and Wellbeing: A Theoretical Inquiry for Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Taikusydän. 2019a. The Heart of Arts, Culture and Well-Being in Finland. Retrieved in Feb 24, 2019 https://taikusydan.turkuamk.fi/english/info/.

Taikusydän. 2019b. Arts and Culture for Health and Wellbeing. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 https://taikusydan.turkuamk.fi/english/arts-for-well-being/.

The History of Equality. 2018. Yle Finnish Public Service Broadcasting Company. Retrieved in Feb 23, 2019 https://areena.yle.fi/1-4018615.

The Ministry of Education and Culture in Finland. 2018. Taide- ja taiteilijapolitiikan suuntaviivat: Työryhmän esitys taide- ja taiteilijapolitiikan keskeisiksi tavoitteiksi. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministerin julkaisuja 2018/34.

TUAS 2019. Turku University of Applied Sciences. Degree Programmes. Retrieved in March, 26, 2019 http://www.tuas.fi/en/study-tuas/degree-programmes/.

Unesco. 2018. Culture for the 2030 Agenda. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 http://www.unesco.org/culture/flipbook/culture-2030/en/mobile/index.html#p=1.

Unesco 2019. United Nations. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform Finland. Retrieved in March 13, 2019 https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/memberstates/finland.

Välimäki, S. 2005. Subject Strategies in Music: A Psychoanalytic Approach to Musical Signification. Doctoral Dissertation. Helsinki: Hakapaino. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/152747/Subject%20Strategies.pdf?sequence=1.

Westerlund, H. 2003. Bridging Experience, Action and Culture in Music Education. Doctoral Dissertation. Studia Musica. Helsinki: Sibelius Academy. Retrieved in March 24, 2019 http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:952-9658-98-2.

Wigram, T., Nygaard Petersen, I. & Bonde, L.O. 2002. A Comprehensive Guide to Music Therapy. Theory, Clinical Practice, Research and Training. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Hyvä ja kiinnostava aihe. Suomeksi kun vielä löytäisin sen.

Olisi minulle ammatinvalinnan paikka.

Hei,

suomeksi tästä löydät juuri ilmestyneestä, vapaasti ladattavasta julkaisusta Musiikkihyvinvointia! Musiikkityö sairaala- ja hoivaympäristöissä. Löytyy Turun AMK:n LOKI-julkaisukaupasta. Seuraa ilmoittelua: syksyllä on haku Kulttuurihyvinvoinnin YAMK-tutkintoon.

https://julkaisumyynti.turkuamk.fi/PublishedService?file=page&pageID=9&groupID=269&action=viewPromotion&itemcode=9789522167118